Class Warfare?

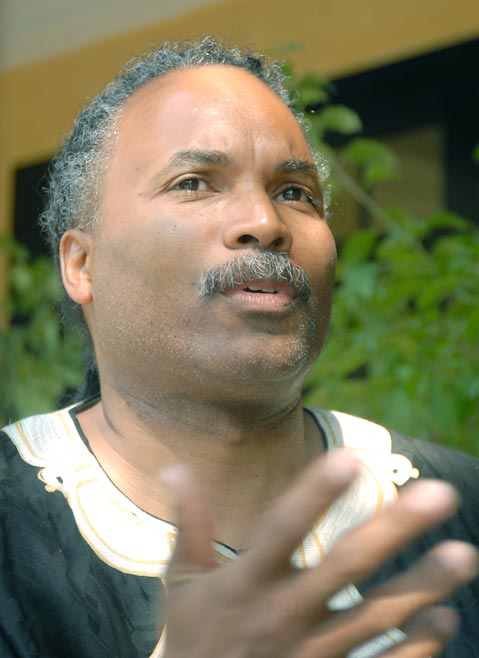

Matef Harmachis Fights for His Right to Teach

Despite being exonerated recently at a State-level

administrative hearing, former Dos Pueblos High School social

studies teacher Matef Harmachis is still fighting for

his job and his good name in the face of what he perceives as race-

and class-motivated attacks from the Santa Barbara School District.

Though a 26-page state hearing board report — not to mention

countless former students and colleagues — deem Harmachis, 49, fit

to teach, the Santa Barbara School Board voted unanimously earlier

this spring to appeal the state board’s decision, upholding its

July 2005 decision to fire Harmachis. While a superior court judge

is expected to rule on the matter sometime this fall, both sides

have recently reiterated their resolve.

Superintendent Brian Sarvis

commented last week, “Simply put, we cannot have Matef teaching

high school students.” And Harmachis — who has been on paid leave

to the tune of $50,000 a year for the better part of two years —

considers his return to the classroom an inevitable issue of higher

calling and karma.

“It’s not up to me and it’s not up to them [the

district],” he said. “They don’t have the power. They can’t do what

the almighty don’t want them to do. … I am going back to the

classroom.”

Fueling the school board’s determination to keep Harmachis out

of the classroom is a series of events dating back to 2004. The

trouble began on a warm June morning at Dos Pueblos High, with the

school year nearly done and Harmachis teaching a mid-morning senior

economics class. Sometime during the class — which was intended to

be a discussion of final-exam results, senior checkout paperwork,

and a customary yearbook-signing session — the atmosphere turned

confrontational. After the smoke cleared and the class bell rang,

Harmachis found himself accused of physically and verbally abusing

two Jewish visitors to his class.

By Harmachis’s recollection, “There were two un-enrolled kids in

my room, uninvited. They acted a fool and I got them out. Case

closed.” However, according to testimony in the state hearing,

things may have gone down a bit differently. The visitors in

question — though unknown to Harmachis — were not strangers to the

school; they were sophomores who had taken the semester off to

study abroad in Israel. Having recently returned home, the twins —

who are sons of prominent local rabbi and Loyola Law School

Professor Arthur Gross-Schaefer — had come to campus that day to

fill out enrollment papers for the following fall and to give a

presentation about their experience in Israel to a different class

later in the day. Their presence in the econ class was not

surprising, as Harmachis’s classes were often attended by other

students eager to hear the popular teacher talk. In fact, on that

particular day, there were six other visitors in the class, in

addition to approximately 30 enrolled students.

The conflict flared when Harmachis asked one of the boys to turn

his T-shirt inside out, considering it a breach of school policy.

The shirt was military green and emblazoned with the words “Israeli

Police Force.” Harmachis and at least one other witness maintain

that the shirt also had an insignia of two crossed rifles on it,

thus rendering it a violation of the dress code; but the twins and

several other witnesses say it did not. According to Harmachis, the

15-year-old boy refused to turn the shirt inside out in a very

confrontational manner. Harmachis then put his hand on the boy’s

shoulder, directed him toward the door, and told him to “cool it”

with a promise to discuss the issue outside the classroom once the

lesson was done. However, the twins testified at the state hearing

that Harmachis said something along the lines of “turn the fucking

shirt inside out,” grabbed the teen, and escorted him outside the

classroom. He then slammed the door and shouted, “Get the fuck out

of my room with the IPF shit, fucking pigs!” Of the eight witnesses

not directly involved in the altercation who also testified, six

went on the record saying they did not recall Harmachis using the

f-word during the incident, and none of the uninvolved witnesses

remembered any racial slurs.

At the request of the Gross-Schaefer family, the district

investigated the incident and placed Harmachis on paid

administrative leave. In the end, Harmachis was reprimanded for

improper language and behavior, but he was not fired, as the

Gross-Schaefers had hoped; instead, he was transferred to Santa

Barbara High School in January 2005 and instructed to curb his

obscenities and refrain from touching students. However,

Harmachis’s trouble was only just beginning. As Sarvis explained,

“The Harmachis situation isn’t just about the T-shirt incident. It

is an aggregate of the sexual harassment and then the incidents at

S.B. High.”

THE PLOT THICKENS

The superintendent

was referring to an allegation by a former female student that

surfaced during the T-shirt investigation. While the student

readily admitted to having a “good” relationship with Harmachis,

she testified that he made comments such as, “Just because you are

good in bed, doesn’t mean you can eat in class”; and, “It is okay

if you come to class naked, but you cannot drink Naked juice in

class.” Further, after serving a suspension, the girl reported her

return to Harmachis’s class was marked by a “weird” hug and a kiss

on the cheek. However, since little or none of the accusations were

corroborated by other witnesses, the state board ruled that the

district had “failed to establish” that Harmachis’s actions

constituted sexual harassment.

By the time he had taken the reins of social studies and history

classes at Santa Barbara High in February 2005, Harmachis felt he

could put the sexual harassment accusations and the T-shirt

incident behind him; he had been cleared. But within two weeks, he

found himself in hot water once again. The first reprimand in his

new school came a mere three days after he started to teach again,

when he shouted at a repeatedly disruptive student in his law

class, “Shut the hell up!” While Harmachis does not deny the

outburst, he counters, “You think a teacher has never yelled shut

up before? Come on now!” Furthermore, he feels, “There should be a

choice on campus and you should take your child out of my room if I

am scaring you. That’s okay. … Choice is good.”

The proverbial third strike came 10 days later when he

confiscated a cell phone from a student in his special-education

U.S. history class. According to Harmachis, the kid was defiant on

a daily basis, and when he refused to turn over the cell phone —

which school policy outlaws in the classroom — the teacher admitted

he “snapped” in his handling of the situation, physically removing

the phone from the student’s shirt pocket and possibly uttering

obscenities. Three days later, on February 17, Harmachis was once

again placed on paid administrative leave, where he remains

today.

Putting aside the expected contradictions of he said/she said

debate, the Harmachis situation is probably most intriguing for the

outpouring of support the embattled teacher has received. From

former students to colleagues, the message is clear: This man can

teach. Liz Bush — who also teaches history at Dos Pueblos and

supervised Harmachis’s student-teaching stint in 2001 — described

him as “head and shoulders above anybody I have ever worked with

before or since.” And Shane Coggins — a former student of

Harmachis’s who was in the classroom at the time of the T-shirt

incident — said recently, “I wasn’t doing too hot in high school

and he made me realize I could go to college; he raised my

awareness of social issues at a time when I needed it most.” Riki

Berlin — a Jewish woman who has worked as a special-education aide

in the district for 25 years and often visited Harmachis’s class —

remembered how parents transferred their kids to Dos Pueblos just

so they could take a Harmachis history class. “He got kids to go

out into the world and try to fix things and to get civically

involved. He was a real inspiration. … It is a true tragedy to lose

a teacher like that who can get kids interested in history,” she

lamented last week. Even Sarvis has offered that Harmachis was a

“spirited teacher who certainly connected with a lot of kids.” But

“there were also some students who were afraid,” he added.

Harmachis acknowledges his tendency to provoke fear and

considers it indicative of what he perceives as the real reason

behind his dismissal. “[The district knows] I ain’t no liberal and

they know I ain’t no conservative,” he explained. “But I hate

oppression and I am out to kill it wherever I find it. Stomp it out

and kill it. People come first with me, no matter what, and I think

that scares other people.” In a district with only 12

African-American teachers, Harmachis feels that “this whole thing

has never been about me. It is about white male privilege and

politics.” To Harmachis — who readily refers to the United States

as an “anti-nigger machine” and often dresses in traditional

African garb — the Dos Pueblos incident would have been seen in a

vastly different light had the roles been reversed; that is, if the

un-enrolled students had been students of color and he an Anglo

European teacher. “I would have had no problems and no complaints

if that had been the case,” he opined. As for the allegations

against him for his behavior at Santa Barbara High, Harmachis

chalks it up to “card stacking” and dismisses it as “just an excuse

to get rid of me.”

Still, Harmachis admits to having made mistakes in the

classroom. “Yes, I need better self-control when faced with

disobedient students,” he said. “From now on, I’ll be the first

person to call the principal or the administration or whoever.” But

that isn’t good enough for Sarvis and the school board, who seem

poised to fight reinstatement to the bitter end. “The board is

resolute in their determination to make sure we don’t see him in

front of a classroom ever again,” Sarvis vowed. “It would be quite

a quandary for us if he wins.” Accroding to Harmachis’s lawyer, Bob

Bartosh, the entire process will most likely wind up costing the

cash-strapped district in excess of $200,000 with no guarantees

that it will win.

Winning or losing seems to be beside the point to Harmachis. A

former journalist and active political organizer, Harmachis

considers his job as a teacher to be part of a higher calling. “I

have no worries,” he explained. “To worry is sin. … Teaching came

to me, I was pushed toward it, and if I just do the right thing,

it’s my assumption that things are going to go right … I am going

to go back and teach exactly the same way I always have. I am good

and they know I am good.” And then, as if addressing his

detractors, he confidently added, “Don’t believe the hype. Come to

my classroom and you’ll see. Not one person who is trying to exile

my career has ever been in my class.”