Saints Alive!

New Mexico Santero Artist Reacquaints Santa Barbarans with St. Barbara

For a town steeped in centuries of Catholic tradition, Santa Barbara is pathetically anemic when it comes to visually celebrating-or even acknowledging-the lives of the saints whose names both grace our maps and define our sense of place. Naturally, I blame the Protestants. Coming to power as part of the great Yankee ascension, Protestants had effectively seized control of Santa Barbara’s myth-making machine by the time of the Great Earthquake of 1925. Red tile roofs and human scale architecture of the Andulucian variety were in; the saints and all the over-the-top agonies they endured were out. As a result, we’ve become a city of liturgical illiterates, more conversant about the difference between S tiles and C tiles than we are with the bloody psychodrama that caused St. Barbara’s father to chop off her head in the first place.

It often takes an outsider to tell us our own stories, and to that end Santa Fe artist and archeologist Charles M. Carrillo will be speaking in Santa Barbara on May 30th–this coming Friday–about the intense passion the saints evoked among those living in Spain’s colonial hinterlands from the late 18th to 19th centuries. Back then, no home was complete without a retablo-or painting of a saint. They were designed as much to provide shelter from life’s cruel caprice and deadly violence as they were for decorative expression. In places like Santa Barbara, relatively accessible by boat, such artwork could be imported from Mexico, Carrillo explained in a recent telephone interview. But in New Mexico, an arduous 12-month journey from Mexico, residents were forced by necessity to produce their own art. Out of isolation, New Mexico spawned thousands of santeros or ‘saintmakers’–artists who specialized in telling the lives of the saints. Often their style was rough-hewn and primitive, but it was a mode of expression, said Carrillo, in which intensity trumped technique. By the turn of the 20th century, that once vital folk art tradition had almost completely disappeared, with only a few determined stragglers holding out.

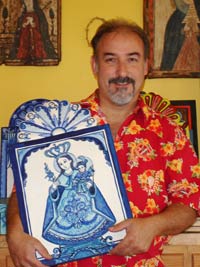

Carrillo fell into what would become his life’s passion 31 years ago almost entirely by accident. At the time, he was a young archeology student working on the ruins of the Santa Rose de Lima church two hours north of Albuquerque. Although entirely unschooled as an artist, Carrillo-who grew up in a devout Catholic household-was seized by the urge to try his hand painting the image of Saint Rose. What started as an itch quickly became a fascination and then an obsession. Carrillo went on to earn his PhD in archeology and now teaches, but his life’s work has been making images and carvings of the saints, deploying the same techniques and materials used 200 years ago. While many artists pay a steep price for pursuing their passions, Carrillo has been exceptionally fortunate. His art not only pays the bills-smaller pieces fetch $200; larger carvings have gone for as high as $60,000–but two years ago, Carrillo received a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment of the Arts for his work as a santero.

His talk in Santa Barbara is titled “Struck by Lightning,” which is exactly what happened to St. Barbara’s father after he killed his daughter for converting to Christianity. During the Middle Ages, St. Barbara ranked among the most popular of all the saints, and was appealed to by those facing imminent death, like miners, ships’ gunners, artillery men, and appropriately enough for architecturally fixated Santa Barbara, architects. (It was Barbara’s addition of a third window-a reference to the Holy Trinity–to the tower in which her father kept her locked that tipped him off that she’d converted.) But in New Mexico, Carrillo said, St. Barbara is regarded as the patron saint against intruders. “Lightning was a frequent and deadly occurrence during the colonial periods; it was not uncommon for people to be hit while inside their homes,” Carrillo said. “It would kill people.” Beyond that, Carrillo noted how many of the colonialists settling in New Mexico were targeted by raiding bands of Comanches, Apaches, and other Native American tribes. “They would steal horses, women, children, cattle, and food,” he said. “They weren’t trying to kill people. They wanted stuff.” With the threat of such incursions a daily reality, it’s easy to understand the powerful appeal a St. Barbara painting might possess. Little wonder, Carrillo said, that in New Mexico, St. Barbara ranked in popularity just behind the Virgin Mary. Almost equally popular was St. Anthony, the patron saint for lost things. “Even though New Mexico was settled by Franciscans, St. Francis never had the appeal that St. Anthony did,” he said, “St. Anthony outranked St. Francis at least by 20-to-1.”

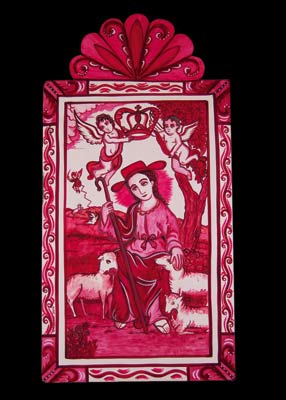

What distinguishes Carrillo’s work is his insistence on historical authenticity. He’s not merely regurgitating a catalog of Catholic saints’ stories–gloriously bloody and violently tragic–and using New Mexico’s lucrative folk art idiom to market them. As an archeologist, Carrillo researched how the original santeros made their own paints and prepared their own canvasses. To the extent humanly possible, Carrillo has replicated how they did it. For the smaller paintings-or retablos-the canvas is actually a rectangular chunk of pine milled from a log. This is then covered with homemade gesso-gypsum powder mixed with glue made from animal hides. This creates a white plaster-like surface on which the paints can be applied. Carrillo uses vegetable dyes, mineral pigments, and clays for his colors. He uses ground turquoise and lapis as the base for certain blues. For a host of pigments covering the spectrum from magenta to lavender, he uses cochineal–insect larvae from a parasite bug that afflicts the prickly pear cactus. It takes up to 70,000 dried insect larvae to make one pound of die. Carrillo orders the larvae in bulk from Mexico. When he’s finished painting, Carrillo coats his image with a varnish that he fabricates using the sap from pi±on trees mixed with grain alcohol. After that, he waxes the entire thing using beeswax.

Likewise, Carrillo said he takes pains to adhere to the aesthetic vocabulary of the period. Carrillo acknowledged that many of his saints bear an uncanny resemblance to himself. But, he added, that was also true for most practicing santeros. Carrillo has been selling his art for the past 25 years with great success at a Santa Fe folk art gallery, the Spanish Market, which places a great premium on such authenticity. It was there that Carrillo became acquainted with several members of the Santa Barbara Trust for Historical Preservation, and it was they who invited him to Santa Barbara to speak.

Carrillo is happy to discuss his notions of “folk” or “platonic” Catholicism and the role of the saints within it. “The concept, at least as it was understood in New Mexico, was that a saint was someone who used to exist on earth, but who now dwells in heaven,” he explained. “But the essence of that saint can dwell in an inanimate object and represent the real person who now dwells in heaven.” While the world has grown immensely more sophisticated since the Spanish Colonial period, Carrillo said the power exerted by the saints and their stories persists. “We’ve become such a modern people, but that need to connect still exists,” he said.

In recent years, Carrillo has sought new means of making that connection, using a decidedly more modern folk art vocabulary. Instead of restricting himself to the materials, techniques, and style of the colonial period, he has embraced the irresistible iconic appeal of the 1953 Ford truck or the 1942 International Harvester to represent the stories of St. Anthony and St. Pascual. With the former, for example, he paints an old Ford-turquoise and brown-with “Tony’s Lost and Found” inscribed on the driver’s side panel. Behind the wheel sits St. Anthony himself. Standing on the seat next to him is the baby Jesus. “That would be illegal now,” Carrillo quipped. Given that St. Anthony is the patron saint for lost things; Carrillo has painted into the back of the truck all sorts of things that are prone to getting lost: a string of Christmas lights, a holster with a gun, shears, and a lantern. Carrillo said his new work has proven extremely popular. “It’s kind of a spoof,” he said, “but I’m not really spoofing them at all. It’s all so the iconography can come alive.”

4•1•1

Carrillo will be displaying and discussing about 20 of his paintings and a few of his carvings this Friday, May 30th, at the El Presidio Chapel, 123 Canon Perdido St. The art showing begins at 7:30; the talk starts at 8:00. Admission is free for SBTHP members and $10 for non-members. For more information, visit sbthp.org or call 965-0093.