Reza Aslan to Speak at UCSB

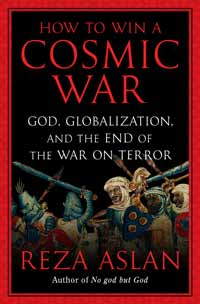

Scholar of Islam Will Discuss His New Book, How to Win a Cosmic War

In 2005, Reza Aslan’s No god but God, about the history of Islam and its role in the modern world, was published to wide acclaim. (The Independent‘s 2006 interview with him can be found here.) Aslan is an assistant professor of creative writing at UC Riverside and a senior fellow at the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies at UCSB. His new book, How to Win a Cosmic War: God, Globalization, and the End of the War on Terror, is about the conceptual faultiness of the “War on Terror”; the historic relationship between religion and violence in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam; and the clash between reformist and fundamentalist elements in the Muslim world.

On Monday, May 4, Aslan will give a free talk at UCSB’s Orfalea Center. Recently, Aslan spoke to me by telephone; the interview below has been edited and condensed.

What is a cosmic war, and why was the “War on Terror” a cosmic war?

A cosmic war is one in which the participants believe they’re acting out a battle on earth that’s actually taking place in heaven: a battle between good and evil. Al Qaeda and like-minded militants are fighting a cosmic war – a war of the imagination. And the Bush administration, by essentially adopting the same cosmic worldview, agreed to fight that war with Al Qaeda.

The problem with a cosmic war is that it’s not fought for political or economic advantages. It’s a war that can neither be lost nor won. The ultimate goal of a cosmic war is to rid the world of evil, which is impossible, absurd, and utopian.

You write in the book that many Christian evangelicals saw the “War on Terror” in Biblical terms, including, perhaps, President Bush. Neoconservatives saw it as an opportunity to bring secular, Western-style democracy to the Middle East. Both of these, you argue, are consistent with a cosmic war.

That’s right. A cosmic war doesn’t necessarily have to be associated with a particular set of religious metaphors and symbols. For the neoconservatives, who really gave shape to the war on terror, there was very much a sense of good versus evil. It was more than just an earthly contest to reshape the Middle East; it was driven by a real and earnest sentiment that the enemies we are confronting are more than just terrorists, but are, in the words of John McCain, a “transcendent evil.”

In the election, McCain campaigned in part on the argument that we’re facing a “transcendent evil.” What contrasts can we see, so far, in President Obama’s approach?

The Obama administration has already made a series of very good choices, chief amongst which is the decision to stop using the phrase “war on terror.” Changing the rhetoric of this conflict, treating the Muslim world with respect, and trying to develop a new kind of narrative in our relations with the Muslim world is a great first step.

However, it’s going to take more than words to win the hearts and minds of the Muslim world. It’s going to take action. The Obama administration has a global economic collapse to deal with, and they’ve only been in power a few months. It’s going to take a long time to change our foreign policy, but I think we can have some confidence that they’re on the right track.

One of the central arguments of your book is that the Bush administration made an error in the way it identified the enemy after 9/11. You write that it conflated Jihadism with Islamism, so that Hamas was tied to Al Qaeda, for example, and Hezbollah to Al Qaeda.

That’s right. One of the principal goals of the book is to draw a very sharp distinction between Jihadism and Islamism. Islamism is a political philosophy. It’s an Islamic form of religious nationalism, and Islamists like Hamas or Hezbollah want to create an Islamic state based on their interpretation of Islam. And while there’s no universal definition of what that means, nonetheless, an Islamist is looking to create a state, either through violent revolution or through a democratic process. A Jihadist is the opposite of an Islamist. A Jihadist wants to get rid of all nation-states. He wants to recreate the globe as a single [Islamic] caliphate.

And you argue that by confusing the two, the Bush administration actually strengthened Al Qaeda and the Jihadists.

Yes. By lumping together all of these various organizations and movements, we created alliances between them. They were given a very simple choice by the Bush administration: You’re either with us or with the terrorists.

A central part of your argument is that Islamist groups can and should be engaged politically. Any solution for the conflict between Israel and Palestine, for example, will have to involve Hamas in some fashion.

Regardless of whether you agree with an Islamist group or not, and regardless of whether they’re violent or not, they want something. They want something very specific and very practical. They may not be able to get that thing; Hamas wants to reconstitute all of historic Palestine. That’s not going to happen. But the fact that they want something at least gives you opportunity to start a discussion. The problem with the Jihadists is that they don’t want anything that can be had in any real terms. What they want is so beyond the pale of the possible that there’s really nothing to discuss. There are no negotiations to be had, no compromises to be made.

How much difference, in America’s relationship with the Muslim world after the Bush years, does it make that Obama is who he is?

It makes a big difference. Obama’s narrative is really appealing to a lot of Muslims, and it’s helped by the fact that he doesn’t shy away from his Muslim background. This is an American president who can say, “I have Muslims in my family. I have lived in a Muslim country. I understand what this faith is all about.” It’s a powerful argument, and it’s one that Al Qaeda has yet to figure out a way to combat. It was easy [for Al Qaeda] to engage with Bush, because Bush spoke the same language as they do. He used the same cosmic dualism that Al Qaeda does. And Obama simply refuses to play that game. He recognizes that the way you win a cosmic war is by refusing to fight it.

4•1•1

Reza Aslan will speak at UCSB’s Orfalea Center on Monday, May 4 at 1 p.m.. For more information, call 893-6087 or visit global.ucsb.edu/orfaleacenter/news.html.