Hope and Help Behind Bars

County Jail Inmates Benefit From Volunteer Programs and Support

Landing in Santa Barbara County Jail is the beginning of a journey. Those charged with major crimes are facing a tough battle within the court system and probable prison time. Others are hitting a bottom created by drug addiction, homelessness, mental illness, or a lack of education and job skills. For the latter, several programs – and people – are providing opportunities to break the cycle of self-destruction and dysfunction.

Inmates can work toward a GED diploma or participate in the Sheriff’s Treatment Program, a structured plan guiding alcoholics into a 12-Step way of life. Parents can be videotaped reading books aloud to their children, with the DVD sent to their sons or daughters as part of the United Through Reading program. Homeless inmates are now discharged to the care of a new program that connects them with social services and shelter.

One of the most important sources of inmate support comes from caring individuals on the outside. Churches of all denominations have a presence in the jail. The ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) is working with jail administrators to re-start the Ombudsman program, by which a volunteer visits inmates to help them address myriad issues and serve as a go-between with the jail. And sober alcoholics “carry the message” into institutions to help others and to enhance their own recovery.

For some recidivist offenders, a jail stay is simply another in a life-long series as they continue to drink or steal or live off the charity of enabling family members. But for those who want help or resources, there’s hope.

James Robertson: Listener and Friend

Working as the ACLU Ombudsman in the Santa Barbara County Jail between 2004 and 2007 is one of James Robertson’s many volunteer efforts on behalf of the incarcerated. The soft-spoken, retired UCSB math professor is a Quaker and got active with his church’s Prison Visitation Support program back in the 1980s. He and others would drive up to the federal prison in Lompoc on a monthly basis to play chess with inmates, some of them extremely sharp players.

Robertson, 72, corresponds with prisoners on Death Row and can be found at Santa Barbara’s Farmers Market every Tuesday opposing execution with the statewide organization Death Penalty Focus. Every once in awhile, one of the people he visited during his cumulative 725 visits to the county jail will stop and say hello.

“I feel a sympathy for these people. I feel like it could be me,” said Robertson. “They are so very grateful for having someone take an interest in their problems. We were there during their low period.”

Robertson emphasized he was not an advocate (legal or otherwise) for people, only a source of information about jail procedures or resources when inmates had questions. He would, however, relay complaints about lack of heating or that the upper bunks didn’t feel secure. Larger men, he said, complained they weren’t getting enough food.

Some of his more memorable encounters include a man who was deaf and mute. Robertson and the inmate took turns writing notes, holding them up against the thick glass wall that separated them. Notably, Jesse James Hollywood had befriended this man and “looked after him,” Robertson said. (Hollywood has been convicted of murder in the death of Nicholas Markowitz.)

The Jail’s overcrowded conditions are hard on the inmates, as are the procedures when someone is suicidal. Robertson recalled a woman who was put into a safety cell, nude. Clothes and sheets are taken away to prevent a person from hanging herself. “People told me that was really traumatic,” he said, pausing for a moment, then adding, “It’s not pleasant to be in jail.”

He fondly remembers helping one woman get released who had been arrested due to a clerical error in her probation proceedings. Other people aren’t so lucky. Robertson was disturbed to hear from one man that he got six years in prison, through a plea bargain, because his lawyer convinced him that a trial may have resulted in a sentence of 25 years to life. The man said he did not commit the crime.

At the end of his stint in 2007, Robertson was visiting the county jail five times per week. ACLU leaders are looking for someone new to be the Ombudsman and recently met with jail administrators to discuss details.

Lt. Mark Mahurin, in charge of the jail’s planning and programs division, said the old program was too unstructured, that Robertson sometimes performed a service the jail was already providing. For instance, inmates can ask legal questions through a service that returns answers within three days. (The jail has no law library.) So, said Mahurin, Robertson did not need to do any legal research.

Mahurin is looking forward to better coordination with the ACLU and gives James Robertson credit for his service. “Robertson has a big heart, but he got run into the ground,” he said.

John: Sober Mentor, Ex-Con

“Everyone deserves a second chance, maybe even a third chance,” said John, a recovering alcoholic who sponsors inmates in the county jail and prisons throughout California. A sponsor is someone who mentors newly sober people, helping them to work the 12 Steps of recovery, either from alcohol or drugs or other addictions.

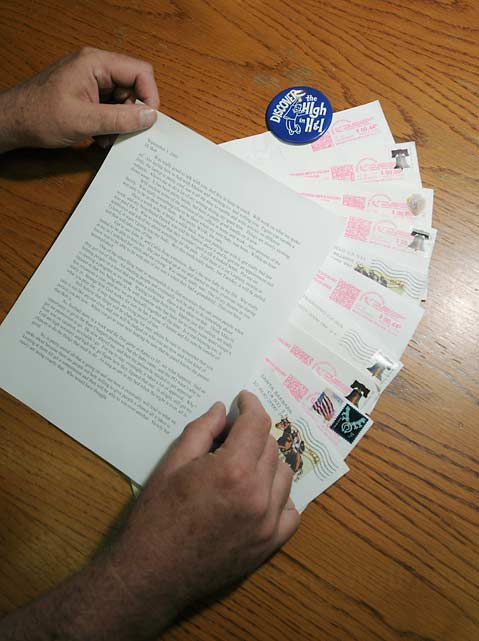

Most jail inmates are allowed to make collect calls freely. And John’s sponsees call him daily. Letter writing is another means of staying in touch – John gets letters from County Jail, the California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo County, Ironwood State Prison in Blythe, among other places. John believes at least 80 percent of people trapped in the criminal justice system have an addiction problem.

His goal is to let incarcerated “newcomers” to sobriety know there’s a system of support waiting for them upon release, that sober alcoholics are ready to take them to meetings and help them establish contact with other people who stay away from bars and old drinking buddies. It’s important, he said, for inmates to feel connected to the 12 Step programs before they are released.

Programs are in place to support John’s work. Alcoholics Anonymous has had a presence in institutions since the first meeting in San Quentin in 1941. Working from the inside out, recovering County Jail inmates live in special housing units, and the Sheriff’s Treatment Program, or STP, places 79 percent of its participants in aftercare or a sober living house.

“People want to change, they just don’t know how,” said John, who himself served 26 years in prison and found sobriety through AA members’ visits and their message of hope. Now he works in the recovery field. “I was told ‘You’re going to die in prison.’ I chose to believe in hope.”