SBIFF ’09: Major Set Approaching!

Irish Surf Flick Waveriders Debuts at Film Fest Wednesday Night

Every once in a while, a salty string from the fabric of the world’s surfing community – offered up for the masses to pull on via film or book or magazine – is so genuinely connected that, by giving it a good yank, you get a look at something all too rare these days: You get to see the act of wave sliding unsoiled, unsold, and untouched by the ebb and flow of a multi-billion dollar international industry. You get see a greater truth about this act known simply as the Sport of Kings that makes sense out of all the seemingly divergent ways and reasons why we play in the ocean.

Such is the case with Irish filmmaker Joel Conroy‘s documentary Waveriders. Set to debut tonight at the Arlington Theatre as part of the Santa Barbara International Film Festival, Waveriders is that rare offering from the world of surfing that simultaneously looks back and forward in such a way that you, irregardless of whether you surf or not, wind up with a better view of where you are right now.

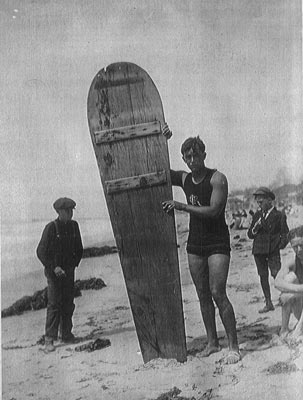

At the center of Waveriders is an often overlooked and regularly forgotten figure from the history of surfing named George Freeth. Born in Hawaii in 1883 to a native mother and an Irish immigrant father, Freeth, besides being the prototypical haole, was surfing’s Johnny Appleseed. After being one of the first reported surfers to actually angle a surf board across the open face of a wave rather than simply steer it straight toward shore, Freeth traveled to the mainland shortly after the turn of the century and immediately began spreading the wave-riding gospel via public surfing exhibitions throughout Southern California.

From there, Freeth became California’s first professional lifeguard and, in the process, became one of the few non-enlisted men ever to earn a Congressional Medal of Honor thanks to his heroic rescue of 11 Japanese fishers off the coast of Venice Beach in 1908. Add to this his notoriety as the guy who gave Jack London surf lessons – thus inspiring London’s now famous surf writing in an issue of Woman’s Home Companion Magazine – and you get a portrait of a man that history, it seems, would be foolish to forget.

Even so, it came as a great surprise to Conroy, himself a lifelong surf addict, when he discovered this undeniably Irish link in the DNA of surfing while reading a newspaper article in an airport several years ago. “For me, finding out about Freeth for the first time was like reading a fairy tale,” recalled Conroy. Instantly, the Dublin-born filmmaker knew he had the makings of damn good movie, especially when he added in some of the elements from his life as surfer in Ireland, such as the big wave exploits of top-notch wave hunters like Gabe Davies, Richard Fitzgerald, the Ojai-born Malloy brothers, and nine-time world champion Kelly Slater.

In short, Waveriders traces a line from Freeth back to his father’s homeland of Ireland and the still emerging, world-class surf scene currently breaking along her green shores today, some 100 years later. “The whole film is contemporary,” explained Conroy with a laugh the other night over pints in Santa Barbara. ” But it’s also historical, if you know what I mean.” And he is absolutely right.

With just about every surfer who graces the screen in Waveriders being born in Ireland or, at the very least, of Irish descent, the film is an ode of sorts to Irish surf culture-complete with some U2 tunes. But to pigeonhole it as just that would be a gross mistake. By showing how Freeth helped give birth to surfing in California and then how, several decades later, some Irish-blooded California-native surfers brought modern surfing back to their ancestors’ homeland – thereby inspiring a whole new generation of Irish surfers – Conroy paints a beautiful, compelling, and oddly timeless picture of what it means to be a member of the surfing tribe. Even better, somewhere along the way, as monster waves roll across the screen and the connectedness of generations is revealed, a hopeful and surprisingly meaningful picture of humanity emerges.