A Werner Workout

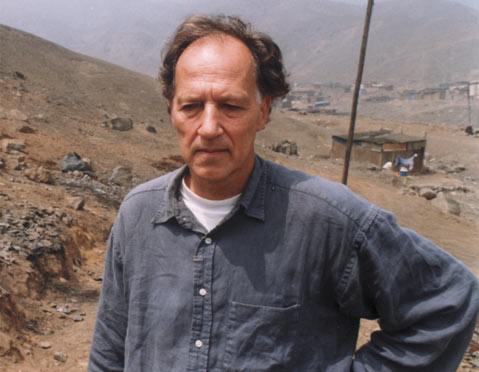

Enigmatic Filmmaker Werner Herzog Says He’s Better Writer than Director

German director Werner Herzog is one of the most accomplished, controversial, and enigmatic filmmakers working in cinema today. He’s made more than 50 films until today, and he’s as masterful in fictional features as he is with documentaries. It was his last doc, Encounters at the End of the World (2007), that garnered him his first—and long-delayed—Oscar nomination.

Known for making symbolic films in exotic locations, Herzog has a reputation for an intense—some would say obsessive—vision and commitment. The movies that made his career starred Klaus Kinski and include Aguirre: The Wrath of God (1972) and Nosferatu (1979). In recent years, he’s had more commercial success and found broader audiences with such films as Grizzly Man (2005), Rescue Dawn (starring Christian Bale in 2006), and last year’s Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (starring Nicholas Cage).

And he’s also on the page too, for last July saw the eagerly awaited publication of his diaries, Conquest of the Useless, which is about the making of his 1982 masterpiece, Fitzcarraldo. In this memoir, Herzog recounts not only the particulars of shooting the difficult film about a fictional rubber baron—which included the famous sequence of a steamer ship being maneuvered over a hill from one river to another—but also his tempestuous relationship with his longtime muse, Klaus Kinski.

I spoke with Herzog in anticipation of his visit to Santa Barbara on April 7 in conversation with Pico Iyer at Campbell Hall, presented by UCSB Arts & Lectures.

Why were you so averse to writing Conquest of the Useless? It was just too painful. I didn’t want to have a look at it. For 25 or 26 years or so, I wouldn’t touch it. I tried it once, and it was just too painful. My wife actually persuaded me to go into it and to give it one last chance. It was technically difficult because [the diary] was in microscopic handwriting, which is not my usual size of handwriting.

But it must have been cathartic obviously 25 years later. No, not really. I mean, one thing was clear through all of the trails and tribulations: Language was my last resort. And I like that America, in a way through this book, discovers me as a writer. The writing is better than my films.

You say this book will outlive your films, and I don’t understand. Your films are classics. When you read it, you will see there’s no one who writes prose like me.

So you think yourself better as a writer? Some of me, yes.

There are several filmmakers who don’t have such a lasting career like you have had and there are some filmmakers who keep making the same film over and over again. But your films from the ’70s are as good as your latest films. No. It’s amusing because the life of a filmmaker is not more than 15 years, 20 years maybe. I don’t know exactly why that is so, but if you look at film history, there are very few who lasted long.

Is there a secret to your longevity? It’s always good if you’re not completely stuck to filmmaking. I direct opera. I write books. That may be one of the reasons, but when you look at people like Kurosawa who was only a filmmaker, he lasted very long. So there’s no clear rule. I can’t give you an explanation.

The trials and tribulations you’ve experienced in shooting a number of your projects, did they find their way into the fiber of the film even if you don’t necessarily see that on the screen? Well, that’s an important question because they always occur, these trials and tribulations. But you have to keep your film out of it; you have to keep your film intact. I think Fitzcarraldo doesn’t show any of the difficulties I went through. When you read the book, it’s an entirely different world.

I wanted to ask you also about the idea of the ecstatic truth, which I’ve heard you mention. (Laughs.) You should be cautious. You need about 48 hours for that one, okay? But just to say one thing in general, yes, I like to look for something beyond the fact and beyond reality, and I’ve always thought that in poetry, in film, there is something such as a deep, inherent truth that we can discover through the lines.

You have started Werner Herzog’s Rogue Film School. There has been an avalanche of people coming at me and not just in these last years but for a long, long time who wanted me to lecture about how to film. It’s in a form of a weekend seminar. I think it has been a very, very successful first round. A long weekend of great intensity. In the first round we had people from Korea and Brazil and Belgium and from wherever, from all over the world.

But this is not your typical film school. I will not teach anything technical related to filmmaking. For this purpose, please enroll at your local film school. It’s about a way of life. It is about a climate, the excitement that makes film possible. It will be about poetry, films, music, images, literature.

You didn’t go to film school yourself. Do you encourage young filmmakers to go to film school? Not really—I think it’s a waste of time. If you travel on foot from Santa Barbara to Guatemala City, you’ll probably, in four or five months of traveling on foot, gain more than four years in film school.

4•1•1

Werner Herzog will be in conversation with Pico Iyer on Wednesday, April 7, 8 p.m., at UCSB’s Campbell Hall. See artsandlectures.sa.ucsb.edu or call 893-3535.