Urban Rescue Team Has Nose for Job

Disaster Dog Detects Victims Who Are Still Alive

When a tractor-trailer rig loaded with gravel lost its brakes one August morning on southbound Highway 154 and ended up plowing into a small wooden house, the Santa Barbara County Fire Department rushed major search and rescue resources to the scene—including Riley, its only certified urban rescue dog.

Four people were living in the demolished structure, but one had reportedly left the building shortly before the truck crushed the others under debris and 26 tons of gravel. Two bodies had been retrieved by the time firefighter/paramedic Eric Gray and his partner, the yellow Labrador retriever named Riley, arrived to determine if anyone was alive under the rubble.

The rubble pile was cleared of rescuers so that Riley, or more precisely his nose, could detect anyone buried alive. He had been trained to know the difference between the scents of living and dead flesh, and to bark when he pinpointed a live person. Dog noses vary in sensitivity—they all are superior to that of humans—but Labradors’ are considered among the best.

Riley quietly followed Gray’s command to “Search” the site of the collapsed house. “He did exactly what he was trained to do, and nothing that he wasn’t,” said his handler. “He went around the pile, going to any place I thought might potentially hold someone. Once I was comfortable he had covered (the area), I pulled him off and told operations it was clear: There were no other survivors.”

Switching to recovery mode, responders soon found the third body beneath the truck. With the recovery of the last victim around 10 a.m., “All fire department operations stopped so that the CHP Major Accident Investigation Team” could do their job, said Capt. David Sadecki, County Fire’s information officer.

It was Riley’s first official deployment, reported Gray, who added that both he and the dog had only recently completed their last disaster certification tests. Meeting federal standards qualified the team for urban search and rescue operations, and to become part of a system of 28 disaster-response task forces across the nation. Because they are called to save lives after disasters, these teams are trained differently from wilderness search and rescue or other canine units used by law enforcement.

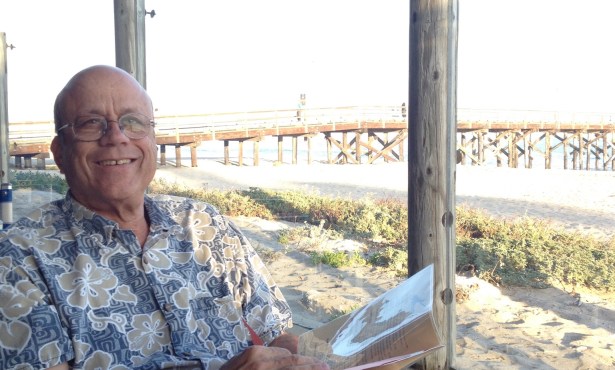

Neither the three-year-old yellow Lab nor his handler were randomly picked to rescue people. Gray has been a firefighter a half-dozen years for Santa Barbara County and is currently based in Santa Ynez. It was during training at the Santa Barbara County Fire Department’s Recruit Academy that he witnessed his first urban search dog in action. Howard Orr, a Fire Department engineer, demonstrated how his chocolate Lab, Duke, worked, during a search exercise in a warehouse.

“I didn’t even know the department had a rescue dog,” recalled Gray. Watching Duke walk past the trainees to search systematically for the “victim” hidden outside in one of the trucks “just blew my mind.” Gray did not know then that these dogs learn to disregard upright humans in the course of their search, but the experience ignited a passion in the young firefighter and dog lover.

Orr, who became Gray’s friend and eventual mentor, is still a firefighter but he chose not to train with another rescue dog when Duke retired in 2008 after nine years of service. The typical working life of human-canine rescue teams spans 10 years, including training. After researching the demands of teaming with a rescue dog, and with the support of his wife, Donna, Gray volunteered to fill the gap left by Duke’s retirement. (Duke is now the Orr family pet.)

Riley was too energetic and curious a puppy to adapt to his original family so he spent time in a dog shelter before he came to the attention of the Ojai-based National Disaster Search Dog Foundation. This nonprofit group owns the dogs it trains and provides, without cost, to search and rescue units across the nation. Over the years the foundation learned that the bold behaviors that make a puppy hard to handle could be honed to create a fine rescue dog, but the animal must rely on its nose rather than eyes to find objects.

Among his new skills, Riley has learned to climb ladders, crawl through pipes, and keep his footing on a variety of perilous surfaces as well as follow scents to high places he cannot see or get close to. His rescue training will continue until he retires.

Despite long hours and the hazardous nature of the search, Gray explained, good disaster dogs enjoy the challenge. “Though this is serious work, for them it’s a (hunting) game,” he said. Riley’s primary reward for a job well done is a favorite toy, not food.

Nevertheless, food is important to a 70-pound Lab, and Wendy Guyer, owner of the Pet House in Goleta, donates most of it. She stepped forward when the Santa Barbara Firefighters Alliance, a support group for local fire departments, was raising funds for the new rescue team, primarily for the kennel and truck used to transport Riley. She wanted to do something long-term and hit on donating a lifetime supply of food.

Guyer thought, “We’re in an earthquake zone; we need this dog. Of course, Eric is a great guy, so I feel I got a bonus.”

A local veterinarian also donates his time and skills to Riley’s care—also for the dog’s lifetime. It is another sign of community appreciation for the dynamic duo.