California Climate Action and Shale Oil Extraction Don’t Mix

In 2012 author and activist Bill McKibben wrote what would become one of the most viewed and widely shared pieces ever posted on RollingStone.com. His article, “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math,” looked at the allowed emissions to avoid dramatic climate change: The world can emit 565 more gigatons of carbon dioxide and stay below 2°C of global warming (about 3.6°F), the increase agreed upon by all nations at Copenhagen as the threshold not to exceed. Burning known fossil fuel reserves presently held by various nations and private companies world over would emit 2,795 gigatons of carbon dioxide — five times the safe amount. The conclusion: the world needs to keep 80 percent of fossil fuel reserves in the ground or risk catastrophic consequences for life on Earth.

What does this mean for an oil-producing state like California?

Covering much of Central California and extending as far south as Los Angeles, the Monterey Shale formation is by far the largest shale oil reserve in the country, with an estimated 15.4 billion barrels of oil according to the Energy Information Administration. The Monterey could hold twice as much recoverable shale oil as the country’s second- and third-largest formations, the Bakken in North Dakota and Eagle Ford in Texas, combined.

This isn’t the conventional oil we’ve been drilling in California for the past hundred years. This is tight oil that can only be extracted through energy-intensive, high-emissions processes like fracking, acidizing, and steam injection. “Well to wheel” analyses (e.g., “Oil Sands, Greenhouse Gases, and US Oil Supply: Getting the Numbers Right,” IHS, 2010) show that like Canadian tar sands, California heavy oil is among the most carbon-intensive in the world — exactly the kind of oil that needs to stay in the ground if we are to head off the worst impacts of global warming.

Let’s look at a specific tight oil project in our county. The 136-well project proposed by Santa Maria Energy up for approval by the Santa Barbara County supervisors on November 12 would generate 88,000 tons of greenhouse gases for the projected production of one million barrels of oil per year. If approved, this project would be one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions in Santa Barbara County, equivalent to adding 17,000+ cars to the road. This project is average for California heavy oil production in terms of emissions.

Now imagine we extract an expected 15.4 billion barrels of shale oil. There’s no exact estimation of the time it would take. Twenty years? Fifty years? Let’s assume conservatively we extract it over the next hundred years. At the ratio of 88,000 tons of greenhouse gases to produce one million barrels of oil, that works out to about 12 million tons of greenhouse gases per year or the equivalent of emissions from 2.5 million cars — roughly the number of vehicles registered in the City of Los Angeles. An oil boom in California means the equivalent of adding an entire Los Angeles’ worth of cars to the state just to get the thick, heavy oil out of the ground — not counting transporting, refining or burning all that oil.

California global warming law AB 32 requires us to reduce emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. A California shale oil boom would make it much more difficult to meet those overall reduction goals. Imagine trying to double the number of cars in Los Angeles and reduce overall emissions at the same time.

A shale oil boom would be a disaster for the environment locally and climate change globally, but lawmakers have yet to get the message. Fracking and other forms of enhanced oil extraction are linked to spills, air pollution, water contamination, health problems, and even earthquakes from waste water injected deep underground near fault lines. And yet even a modest bill to put a moratorium on fracking until a regulatory program is put in place in California failed 24-37 on May 30. An analysis by maplight.org showed that those voting “no” on the bill received, on average, 31 times as much money from opposing groups like the Western States Petroleum Association as from supporting groups.

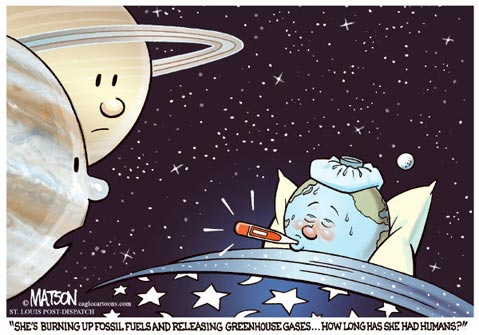

Christiana Figueres, the head of the UN body tasked with delivering a global climate treaty, recently broke down in tears as she spoke about the impact of global warming on coming generations. “I just feel that it is so completely unfair and immoral what we are doing to future generations; we are condemning them before they are even born. We have a choice about it,” she told the BBC.

In California that choice is stark. We are rich in sun and wind and could be a global leader in climate action, setting bold goals for clean energy, ushering in a revolution in transportation, and building a sustainable economy for future generations. Or, we could ramp up production of some of the most carbon-intensive fossil fuels in the world. The climate crisis won’t solve itself, but it is solvable. Professor Mark Jacobson of Stanford University suggests a plan involving an energy infrastructure based on wind, water, and solar power that would provide sufficient energy to power the entire world. The prerequisite is facing the problem head on, holding our leaders accountable — and doing the math.