The Day ‘The Greatest’ Was Born

The War of Nerves in the Ali-Liston Fight

The legend of the world’s best-known athlete was established in Miami Beach on February 25, 1964, when a boy entered the ring against Sonny Liston and emerged from it a man. A young Muhammad Ali was not yet a great fighter, but he managed to beat one. And it shook up the world.

On paper, the bout appeared to be a mismatch of epic proportions. Liston, the heavyweight champion and a 7-1 favorite, was thought to be unbeatable. Cassius Clay, as he was then known, had yet to fight a top-flight contender and had looked bad in his previous two fights against blown-up light heavyweights.

Not one of the 11 living former heavyweight champs gave Clay a chance of winning. Many boxing people sincerely feared for his life. Moreover, Clay’s entire Louisville Sponsoring Group, including his trainer Angelo Dundee, was opposed to him fighting Liston.

As it turned out, the “Louisville Lip” had everybody right where he wanted them.

After much thought, Clay realized that what he did to Liston outside of the ring might be even more important than what he did to him inside of it. Getting the champ to underestimate him was the most important thing.

“I wanted him thinking that all I was was some clown, and that he would never have to give a second thought to me being able to put up any real fight when we got to the ring,” Ali admitted later. “The more out-of-shape and overconfident I could get him to be, the better.”

Equally important was Clay’s plan to needle, harass, and humiliate Liston so badly that he’d fight angry. “Any time you lose your head, you’re fighting the other guy’s fight, and you’re in trouble,” said former featherweight champ Willie Pep. “You know what I call an angry boxer?” echoed Jack Dempsey. “I call him a lost-head. He’s lost his head, and now he’s going to lose the match.”

Clay relentlessly demeaned Liston whenever he could, attacking his intellect and questioning his blackness. By fight time, Liston’s anger had all but consumed him.

Clay’s campaign of psychological warfare might be the biggest sting operation in the history of sports. Remarkably, it was devised by a teenager who had graduated 376th in a high school class of 391. So much for book smarts.

“Nobody ever could have conned me the way I did him,” Ali said. “I’d sit down and give his actions careful examination. Liston didn’t never even think about doing that. Neither did nobody around him.”

The fight became a primer on how not to prepare for a title defense. Liston truly believed Clay’s best weapon was his mouth. He told boxing historian Jimmy Jacobs to bet his life that Cassius wouldn’t last three rounds against him, and he trained accordingly.

Sonny whiled away many evenings eating hot dogs, drinking beer, and dealing blackjack, and a couple of people claimed he was being supplied with prostitutes by members of his entourage. Judging by the activity at Liston’s Miami residence, his victory party began about three weeks before the fight.

But Liston was an old fighter, perhaps twice as old as Ali at the time of their first bout. And a severely injured left shoulder found him secretly spending almost as much time at his physical therapist’s office as he did in the gym.

Between March 9, 1961, and February 24, 1964, Liston fought only three times, each of which ended in one-round knockouts. The sum of his ring time was 6 minutes and 14 seconds, which meant that for all practical purposes Sonny was in the midst of a three-year layoff.

“A fighter has to fight regularly to be at his best,” said Joe Louis. “Jack Dempsey found that out the hard way, and so did I.” And so would Sonny. As Ali would later say, Liston was the perfect setup.

In contrast, Clay trained diligently and led such a chaste life that Angelo Dundee said a lot of people thought his fighter must be gay. The challenger also made sure that nobody but his own people saw his serious workouts. He worried that the press would figure out his strategy, but it never happened.

“Them newspaper people couldn’t have been working no better for me if I had been paying them,” he said later.

A lot of sportswriters intensely disliked both fighters, partly because they thought one had no ability and the other had way too much. They derided Clay’s boxing skill because they were too blind to see it, and they slandered Liston’s character because they wouldn’t allow themselves to believe that he had any.

The backdrop for this fight was essentially one of David versus Goliath. It pitted a talented, engaging, and good-looking kid who thought he was ready to fight the toughest, strongest, and most menacing man that boxing had ever seen. But that story line was about to change in a big way.

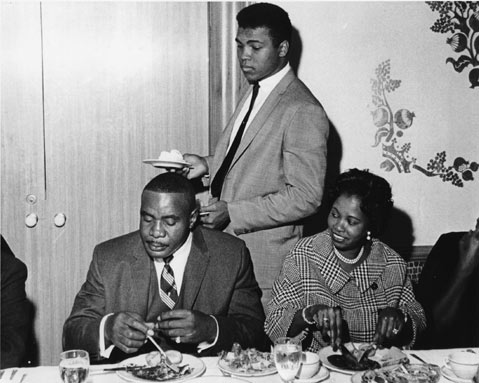

Clay had converted to Islam and was so close to Malcolm X that he invited him to his training camp in Miami. When promoter Bill MacDonald learned of this, he threatened to call off the fight unless the challenger publicly renounced his religion. Clay wouldn’t, and MacDonald allowed the fight to take place only because Malcolm agreed to leave camp.

According to Malcolm’s wife, Betty Shabazz, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad had cautioned Malcolm not to align himself too closely to Clay, fearing that the Muslims would be embarrassed by the fight’s outcome. “You will not in any way be representing us, because it’s impossible for Cassius Clay to win,” said the Nation’s leader.

Now the fight had two bad guys, and some people thought Liston, an ex-con with mob ties not of his own choosing, was the more sympathetic of the two. At best, though, he was merely the lesser of two Negro evils.

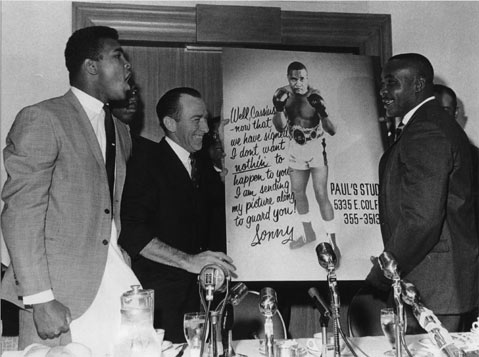

The weigh-in was more memorable than the fight. Clay’s carefully rehearsed routine was probably the finest acting performance ever staged by any athlete. His feigned hysterics were so convincing that the boxing commission’s lead doctor said Clay was emotionally unbalanced and liable to crack up before he entered the ring. He said the fight would be cancelled if Clay’s heart rate and blood pressure were still high at fight time.

The spectacle reaffirmed everything that the challenger had wanted Liston to believe about him. “It really got next to him,” said Sonny’s trainer, Willie Reddish. “I could tell by the expression on his face. Clay was acting like a crazy man.”

And that was hugely important because as Sonny once said, the worst person in the world to fight is a crazy person. Geraldine Liston said that was exactly what her husband thought of Clay. “You never know what to expect from a man like that,” she added. “You never know what to expect from a madman.”

Of the 58 sportswriters that were polled, 55 picked Liston to win, and most of them predicted an early knockout. As a result, the arena and the country’s closed-circuit outlets would be little more than half full. Several sportswriters thought Clay might not even show up.

“The tension was electric,” said Clay’s physician, Dr. Ferdie Pacheco, “but this tension was more like that of an audience at a hanging. They were here to see this kid get his. When he was going to get it was the only question.”

Muhammad Ali never denied that he was afraid of Sonny Liston, though he downplayed it. However, in his dressing room, Clay’s fear was so palpable that he accused Dundee and Pacheco of being Mafia people who bet with gangsters. He trusted no one but his brother, Rudolph.

“You have to remember one thing,” Ali’s close friend Gene Kilroy said later. “Sonny Liston was a man. At that time, Muhammad Ali was a little boy.”

When the opening bell sounded, Liston’s pent-up rage caused him to chase the fastest heavyweight in history around the ring. “Man, he meant to kill me. I ain’t kidding,” remembered Ali. Liston became the bull, and Clay happily accepted the role of matador. A 22-year-old kid had baited a trap, and the Bear stepped right into it.

After the third round, Rocky Marciano turned to his radio partner Howard Cosell and said, “Jesus Christ, Howie, he’s become an old man.” Sonny’s close friend, casino executive Ash Resnick, said it looked like Liston had aged 10 years right before his eyes.

The fight was even on the official scorecards after six rounds. But Liston was exhausted, and the painful injury to his left shoulder rendered his left hand — the most potent weapon in boxing history — useless. When his corner stopped the fight, tears trickled down Sonny’s cheeks. The eight physicians who examined him concluded that the injury would have prevented him from defending himself.

To underscore the enormity of what had taken place, Joe Louis matter-of-factly stated that Cassius Clay had just beaten the greatest heavyweight champion in history.

The new champ berated reporters and screamed at them to eat their words. “I just beat Sonny Liston,” he said. “I must be the greatest!” And he has been ever since.

Asked how he felt about losing his title, Liston said he felt “like when the President got shot.”

A four-week investigation by the Florida State Attorney revealed no evidence that the fight had been fixed. The report found no fluctuation in the betting odds anywhere in the country and confirmed the findings of the physicians who examined Liston. Nevertheless, a lot of sports fans still believe that fight was fixed.

But what nobody disputes is that Muhammad Ali’s victory over Sonny Liston gave birth to a sports icon who would become the most famous athlete of all time.

Santa Barbara resident Paul Gallender is the author of Sonny Liston – The Real Story Behind the Ali-Liston Fights.