Who Killed Linda Archer?

Cops Crack 18-Year-Old Cold Case with DNA Match

Linda Louise Archer struggled with heavy-duty mental-health challenges that eventually hurled her onto the streets of Santa Barbara. During the last few weeks of her life, those struggles intensified. The 43-year-old mother of two — remembered as being quiet, subdued, and better groomed than one might expect a homeless person to be — grew increasingly agitated that she was in physical danger. People, she told friends, were out to get her. For protection, Archer armed herself with mace. She carried a knife.

Archer may have been mentally ill, but it turned out she was far from crazy. On August 16, 1997, someone bludgeoned her to death, repeatedly smashing her face and head with what was most likely a tree stump. Archer’s body would be found in a concrete culvert visible to drivers getting off Highway 101 at Castillo Street. The knife she kept for protection had been stabbed into the ground just a few inches from her body.

Twice police investigators thought they had Archer’s killer. Twice they would be proved wrong. And for the past 18 years, her murder would remain almost as big a mystery as her life. Archer joined the ranks of 26 other unsolved murders — the earliest dating back to 1961 — that make up the Santa Barbara Police Department’s Cold Case file.

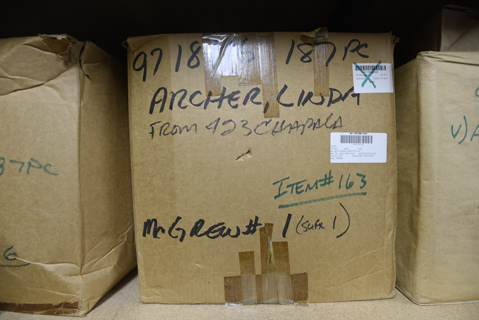

In the warren-like basement of police headquarters, there’s a cramped storage room known as the Dead Room. Jammed inside are boxes containing all the physical evidence accumulated for Santa Barbara’s cold cases. There are 20 for the Archer investigation. In addition, there’s the blood-splattered tree branch found next to her. The actual murder weapon is stored elsewhere. So are seven binders containing more than 1,000 pages of notes.

Now leading the investigation is Detective Andy Hill, a 17-year veteran of the department. Hill was born and raised in Santa Barbara, graduating from San Marcos High School. Solidly built but not big enough to seem physically imposing, Hill — to a striking degree — does not radiate cop. He genuinely likes to talk. He’s inventive with language. He’s an even better listener. It’s a big part of the reason people tell Hill things they shouldn’t.

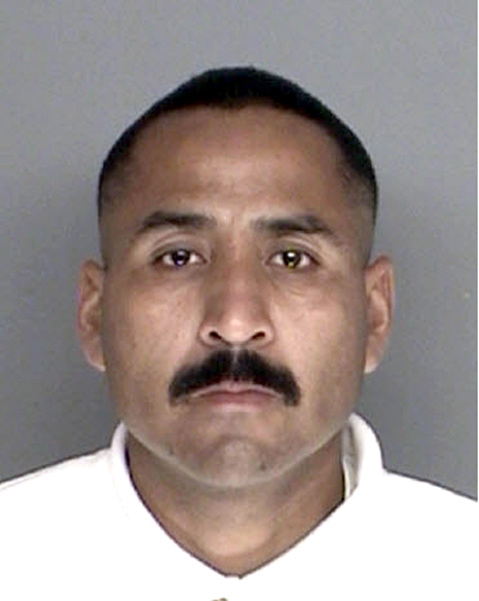

About a year ago, an on-again, off-again Santa Barbara resident named Manuel Salmeron Manzanares told Hill some things he probably shouldn’t have. Those things had to do with Linda Archer.

Third Time’s the Charm

At the time, Manzanares, now pushing 37, was serving a sentence in the Lompoc Federal Penitentiary for illegally reentering the United States after being deported. A lifelong addict with a long list of felony convictions and aliases, the Mexican-born Manzanares — a house painter by trade and attendee of Santa Barbara public schools — had been deported twice before. Hill and Manzanares talked in a prison room where desks had been stacked on top of each other to create a semblance of a meeting space. Hill delivered what he described as a very detailed and carefully prepared “monologue.”

Manzanares listened.

That the meeting happened at all required Manzanares’s consent. Hill knew he had only one shot at what he was about to do. But he had an ace up his sleeve. Hill waited until the very end before playing it. “Tell me why your DNA is on the person of Linda Archer,” he demanded.

Manzanares got flustered. Eventually he spoke. For reasons having to do with legal strategy coupled with an abundance of institutional caution, neither Hill nor any of his departmental superiors are willing to categorize Manzanares’s statements as a confession. But for all practical purposes it was. Hill said Manzanares “got some things off his chest that he’d been holding on to a long time.”

In TV crime shows, a DNA match leads inevitably and irresistibly to conviction. But in the real-world investigation of Linda Archer’s death, a DNA match by itself might not be enough. In the less-than-pristine environs of a homeless camp, there’s no shortage of possible explanations how one person’s DNA got mingled with someone else’s. “That would have been a lot harder to overcome without [Manzanares’s] statements,” Hill said.

Hill returned to Lompoc after their first meeting last July, but Manzanares refused to meet with him. “I’d say he’s conflicted,” Hill said.

On June 12 this year, Manzanares was released from Lompoc, having completed his federal sentence, and was immediately taken into custody by Santa Barbara police for the murder of Linda Archer. Since then he’s been parked in the Santa Barbara County Jail, awaiting trial or, more likely, a negotiated settlement.

Without Manzanares’s statements, defense attorneys would have had an obvious line of attack. City police mistakenly thought they had the killer two times before.

The first suspect, Gregory Gavin, shared a campsite with Archer. When police first encountered him, he appeared to have blood on his clothes. His girlfriend was wearing shoes taken off Archer’s feet. And he’d buried several other possessions belonging to Archer. But what was thought to be human blood was more likely — according to one investigator — Chinese food. And if Gavin acted weirdly, that was consistent with how he’d behaved during his 20 years on the streets. He was cut loose before charges were ever filed.

Sergeant Mike McGrew, then a detective, headed the initial investigation, and from early on, he had his eyes on John Dalton, a violent sex offender paroled to Santa Barbara after raping his sister with her 2-year-old in the bed. “He was a serious bad guy,” McGrew said. Dalton had been seen with Archer the night before her death. His girlfriend at the time told police he’d told her to lie to establish an alibi. Thirty minutes after the crime, the girlfriend claimed, Dalton had shown up in her room at the Virginia Hotel to wash blood off his hands. Cops seized the hotel room sink. No blood was detected. Even so, the sink remains stored as evidence in the Dead Room.

McGrew made it his mission in life to bird-dog Dalton. The conditions of his parole prohibited Dalton from drinking. McGrew made sure Dalton’s parole officer knew every time Dalton had a drink. When Dalton was sent to prison for such violations, McGrew visited him there. When Dalton was released, McGrew was waiting.

Murder charges would not be filed until 2000, however, after Dalton’s cellmate at Corcoran State Prison notified authorities Dalton confessed to killing Archer. Dalton believed all women were evil, the cellmate said, and that Archer was especially evil. McGrew thought the confession was genuine because Dalton told his cellmate things he believed no one but the killer could have known. Dalton denied making any such admissions, but he was arrested for murder and held in County Jail for about a year.

Halfway through his preliminary trial, however, Dalton’s DNA tests came up negative. He, too, was cut loose. Dalton would be killed while jaywalking across the Las Vegas Strip in 2006. Looking back, McGrew said, “That guy definitely did not like me. But I guess I can see why, given that he didn’t do it.”

Craving Closure

Unsolved murders are notoriously hard on victims’ families, who find themselves forced to navigate indeterminate sentences of suspended agitation pending some break in the case. With cold cases, it’s trickier still. “Where you were 25 years ago is very different from where you are today,” said Megan Riker-Rheinschild of Santa Barbara County’s Victim Witness Assistance program. “You’re dredging a lot of really old stuff.” For cops, there’s no simple approach. “It’s difficult,” said Sergeant James Ella, who heads the department’s Crimes Against Persons detail. “A lot of family members don’t want to be contacted unless we make an arrest. Some want to be kept apprised anyway. It’s hard.”

Santa Barbara Police Chief Cam Sanchez started a cold-case-crimes unit soon after he was appointed chief in 2000. Based on budget considerations, that unit has been disbanded and its function absorbed by the nine Crimes Against Persons detectives. One day a month, the detectives and their supervisors meet to discuss any developments. To the extent there’s hope, it’s in the evolving technology of DNA analysis.

Archer grew up in Monrovia, the third of five kids. Both parents were born in Massachusetts, and both were dead by the time of her murder. Her father served in the military during WWII and worked as a welder in the aerospace industry after. That they were buried in separate cemeteries suggests divorce, but not much is really known about Archer’s early days. “She came from an average middle-class family and was raised in an average middle-class neighborhood,” Hill said. She had two kids in her teens with a man named Archer. That relationship would not survive her early twenties.

Whatever mental-health issues she had, Hill said, were accelerated by the use of drugs. Slowly and gradually, it seems, Archer’s life fell apart. “She lost things,” Hill said, meaning her car, her job, and connection to her children. At some point, she became homeless, traveling the loop between Santa Cruz and Santa Barbara. At the time of her murder, police said Archer had been in town a year. She made beaded jewelry and sold it in city parks. She didn’t panhandle and kept a decidedly low profile. Archer never asked for help or services, recalled Ken Williams, then a county social worker. “She just didn’t belong,” he wrote shortly after her murder. Only when you looked closely, he stated, could signs of stress be detected. “The eyes were always on guard as if she expected trouble around the next corner.”

Homeless camps are notoriously dangerous for women. McGrew recalled Archer being tough and ready to stand her ground. Earlier that same summer, a 42-year-old homeless woman had been raped and killed on the 500 block of East Cota Street. A 44-year-old woman, not homeless, had been raped and killed behind the Carrillo Hotel — now the Canary. None of those murders would be linked to Archer’s. But clearly, they would have fueled Archer’s sense of imminent danger.

Before Hill was assigned the Archer case, it belonged to Detective Brian Jensen. It was Jensen who discovered in December 2012 that the DNA samples initially taken off Archer had not been uploaded into CODIS, the nationwide databank linking DNA samples and all individuals convicted of felonies. By January, Jensen rectified that omission. Five days later, he got a match. It was Manuel Manzanares. Back in 2000, DNA samples were not automatically sent to CODIS (Combined DNA Index System) as they are now, Sergeant Riley Harwood said; instead, they were sent to private labs.

Hill took over the Archer case in February 2013. His first order of business was to find out who Manzanares was. “I was trying to find family members, friends, employers who could tell about his character, habits, temper, so we could create a picture of who he was back then and who he’d come to be.” Hill sees Manzanares’s criminal profile — court records show car thefts, spousal abuse, Social Security Card forgery, strong-arm robbery, drug possession — through the lens of a “struggling addict.” In other words, Manzanares did what he had to to feed his addiction. Hill also had to navigate multiple aliases to determine when Manzanares could have been in Santa Barbara and when he was behind bars. Nothing he found out precluded Manzanares from being the killer. (Assuming police are right about Manzanares, the Archer murder preceded any deportation efforts.)

Hill then set out to track down witnesses from the initial Archer investigation. It proved easier than he expected, though it required trips to San Luis Obispo, Arizona, and Los Angeles. They helped reestablish time lines essential for any successful prosecution. But not one of the witnesses knew anything about Manuel Manzanares. “He was completely off our radar,” Hill said.

Final Chapter?

In 1997, Manzanares was 18, couch surfing, and quasi-transient. He used services available to homeless people. Of Manzanares and Archer, Hill said, “They didn’t travel in any of the same circles, but they physically used the same routes to get to their respective destinations.” As to what triggered the eruption of violence that left Archer dead, Hill knows but isn’t saying. “Let’s just say it’s not a mystery,” he explained.

K.C. Williamson, attorney for Manzanares, declined to comment on the particulars of his client’s case other than to say he’s currently wading through 1,000-plus pages of discovery. Typically cases as seemingly strong as the one against Manzanares settle before going to trial, but not always. Detective Hill cautioned, “It all depends what the offer is,” referring to how much time Manzanares might have to serve.

To the extent Archer kept in touch with any relatives during her life, it was with her youngest sister, Elizabeth. According to Hill, she helped raise Archer’s two children and bore the brunt of Archer’s “lifestyle choices.” For her part, Elizabeth had no interest in talking. “If this person is found guilty, I may have something to say,” she said via email.

For the time being, Manzanares is being held on $1 million bail.