Refugio Oil Spill — Two Weeks In

Damages Pile Up, First Lawsuit Filed, New Legislation Proposed

Two weeks after the Refugio oil spill, the ruptured section of Line 901 has been excavated and shipped off to an undisclosed location in Ohio for investigation, and a brand-new pipe had been installed and painted green. Though the ruptured section of pipeline is gone — and many details about it remain undisclosed — more than 1,000 workers, researchers, and personnel are still on scene. Many questions linger about the infrastructure’s lack of an automatic shutoff valve, the federal agency known as Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, and about the remaining time frame for restoration efforts. Likewise, impacts to fishermen, wildlife, tourism, the area oil industry, and bureaucratic oversight are still pouring in.

Fishermen Feel the Pain

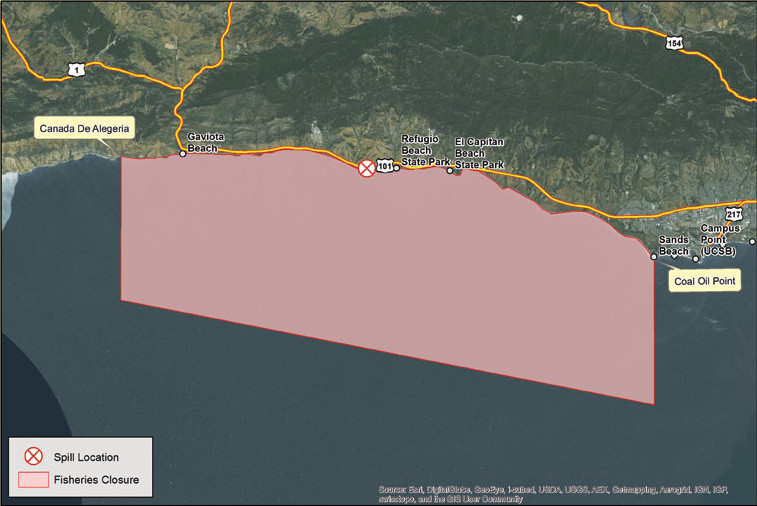

No one knows how long the 138 square miles of fisheries blocked off after the spill will remain closed. But the closure hasn’t stopped some fishermen from venturing past the boundaries. Game wardens have made contact with some, but no one has been cited. One shrimper was forced to dump an entire batch — reportedly $3,000 worth — back into the water. At the time, fisherman Mike McCorkle contended, the shrimper was in water 430 feet deep. “It’s a joke,” said McCorkle of the large size of the closure. “We fish there all the time.”

California Department of Fish and Wildlife spokesperson Alexia Retallack confirmed the wardens so far have been issuing warnings. It’s up to the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment to lift the closure, and that depends on the lab results from samples collected this week, said Hazard Assessment spokesperson Sam Delson, a process expected to take two weeks. Another round of samples will be collected during the second half of June. “We take samples until we find that fish and shellfish have contamination below the level of concern,” he said.

As of press time, 11 dolphins — some with mouths full of tar — and 42 sea lions covered in oil have died and washed onto South Coast beaches, according to the Oiled Wildlife Care Network. One dolphin and one sea lion were found as far south as Oxnard. In the last two weeks, a total of 53 mammals and 87 birds have been found dead. Of the 57 live birds and 38 mammals rescued, eight birds and seven mammals died in care.

Elephant seals and sea lions rescued are being transported to SeaWorld in San Diego because it’s the closest facility that can properly treat oiled marine mammals, according to a spokesperson in the Joint Information Center. Pelicans are being cared for at a facility in Los Angeles.

Deflated Tourism?

Without a doubt, the Santa Barbara Channel fishing trade — a $6.5 million industry — will experience the most immediate economic shock from the spill. This week, fisherman Stace Cheverez filed the first legal complaint against Plains All American Pipeline, a complaint that seeks class-action status.

Ironically, as the hospitality industry braces for impact from the spill, some hotels, namely the Ramada Santa Barbara in Noleta, are benefiting in the short term as hundreds of researchers, industry reps, federal and state personnel, and cleanup crewmembers have booked hotel rooms for two weeks.

But Santa Barbara Region Chamber of Commerce president Ken Oplinger feared that national media coverage has given the impression that the spill “is happening right here in town.” Likewise, Michael Cohen, owner of Santa Barbara Adventure Company, said several people have tried to cancel trips to the Channel Islands even though they are reportedly not affected by the spill.

The most dramatic display of activism since the spill took place last Sunday at the De la Guerra Plaza, where nearly 500 people gathered before marching down State Street to West Beach. The crowd formed a human boom at the waterfront to symbolically stem the rising tide of U.S. oil and use the damage it does to natural environments. The day before, the Unified Command — headed by the U.S. Coast Guard and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — held an “open house” for members of the public to ask questions.

There Will Be Trucks

ExxonMobil representatives are expected to file an emergency application this week to truck oil out of its Las Flores Canyon facility to processing plants across California. Currently, crude that was destined to move through the ruptured pipeline is stored at Las Flores, but ExxonMobil only has about a month of storage capacity left. According to Glenn Russell, director of Santa Barbara County Planning and Development, company reps hope to operate the plant at one-third its normal capacity of 30,000 barrels a day, meaning ExxonMobil would be dispatching nearly 100 trucks a day.

If the county does not grant the permits, ExxonMobil will soon be boxed in and effectively shut down until the pipeline is repaired and gets federal approval to transport oil again. Currently, Veneco and Freeport-McMoRan — each producing 3,000-4,000 barrels a day — have exhausted their storage capacities and have effectively stopped operations. The decision to grant the emergency permits belongs solely to Russell. If he chooses not to grant them, the process to gain permission to truck oil through regular channels would take at least months.

Much speculation has centered around the absence of an automatic shutoff valve on Line 901, raising the question, would such equipment have prevented the spill? Plains claimed in a statement that these types of valves are not appropriate and are unsafe because automatically closing a valve creates an increased pressure beyond a crude-oil pipeline’s capacity. Richard Kuprewicz, president of a pipeline safety company, called this logic “blatantly false.” Ultimately, speculated Andrew Kendrick, a pipeline integrity consultant, several factors likely caused the failure. [Both are interviewed at independent.com/shutoff.]

Legislative Reaction

State Senator Hannah-Beth Jackson and Assemblymember Das Williams wasted little time crafting several new bills that they contend would reduce the chance of future pipeline spills and minimize the damage inflicted should such ruptures occur.

Williams introduced a bill that would require any pipeline company to install automatic-shutdown equipment on any stretch of pipe crossing environmentally sensitive habitat. Plains is the only oil company in Santa Barbara County without such equipment, Williams noted.

Williams went on to dismiss arguments by Plains CEO Greg L. Armstrong that automatic-shutdown valves — and their attendant pressure surges — can pose serious safety problems. Williams quoted an oil-field expert who’d dismissed Armstrong’s concerns as “patently false.”

Jackson proposed three measures, one requiring more-frequent pipeline inspections, another returning inspection responsibility to the California Fire Marshal — it’s now done by the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration — and the third requiring two cleanup vessels equipped with oil skimmers be stationed in Santa Barbara at all times. It took six hours, she objected, to dispatch two such vessels from their mooring in Los Angeles to Refugio.

She would also impose new fees on oil companies, she said, to help bridge the gap between what the state and the oil companies can pay pipeline inspectors. Jackson objected that oil companies “lure” skilled state inspectors away by paying two to three times what the state Fire Marshal can. As a result, the Fire Marshal office has had difficulty keeping and recruiting inspectors. In addition, Jackson’s legislation would ban the use of chemical dispersants in offshore-oil-spill cleanups. None, she noted, were used at Refugio.

On Wednesday, Representative Lois Capps wrote a letter to the House Committee on Energy & Commerce, urging a field hearing in Santa Barbara. “While the exact causes of this spill are still being investigated, this incident highlights the inadequate oversight provided by the pipeline’s federal regulator, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA),” Capps wrote.

Last week, Capps sent a letter to PHMSA, asking officials to provide the public with answers. Capps asked about the timeline of events on May 19, emergency shutoff equipment and shutoff valves, as well as when the formal analysis of Plains’ inspection that took place two weeks before the spill will be released to the public. Senators Barbara Boxer, Dianne Feinstein, and Edward Markey of Massachusetts sent a similar letter to the federal oversight agency.

Brandon Fastman and Keith Hamm contributed to this story.