My Life: Heiress

Treasures My Mother Gave Me

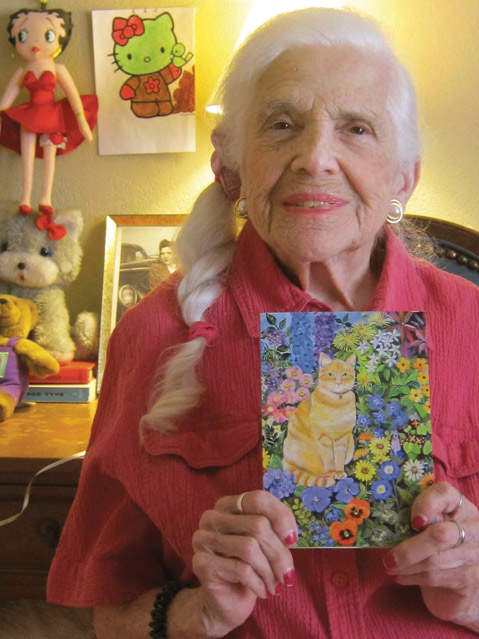

It was two weeks after my mother’s death, and I was clearing out her room at the assisted living facility. Her familiar clothes hung in the closet, and I knew which were her favorites and the provenance of each. The drawers brimmed with beads and broken watches, eyeglasses and trinkets, fancy fans and shoe horns, random treasures neatly wrapped and taped in tissue paper: a screw, a domino, a broken piece of star. I saw the dolls whose names were Darling and Miranda and good old Betty Boop and the steadfast white bear with the heart on his chest who sat on the bed pillow through many hard times. Now they were gathered together like orphaned children awaiting their destiny.

I approached the task in a trance-like state, muting my emotions, thankfully accompanied by a friend. Our sorting system consisted of bags for the Goodwill, the dumpster, and stuff to be kept. “Take your time,” said my friend, now and then pointing to something of potential value, whether real or sentimental. “Are you sure this isn’t something you’ll wish you’d held onto?” But I was ruthless in the giving and the throwing away.

So many hair ties and barrettes, so many ChapSticks and lipsticks, so many unwrapped butterscotch candies, so many pens and crayons and letters and cards, so many handkerchiefs and scissors and Post-it notes and magazine clippings and mirrors and napkins and pictures of kittens and brochures with smiling people on the covers, so many books with handwritten notes tucked into them, so many purses and keys to nowhere, so many emery boards and Band-Aids and a secret stash of hearing aid batteries. Cash, too: a long-forgotten dollar bill folded into a tiny pink coin purse and 79 cents’ worth of change. And there were everywhere photos of people she loved, and they of course were the same ones I loved, the original cast of characters. She and I had sat side-by-side many times looking at those photos, and she never forgot who they were. Days before she died, I showed her the framed picture of my father, and she leaned forward and kissed it.

Life moves along too fast, too fast, but after a while we look back and see what wasn’t clear to us while everything was happening. Discarding the remnants of face powders and blushers, I recall that my mother liked to look pretty, and how surprised she was to see her face in the mirror, grown old. “But I can still run,” she told me once at the age of 89, “If I ever had to run, I could run.” Scary thought, but it’s how she saw herself, and even after she fell and broke a hip, she swapped her cane for a walker and kept on moving briskly. She hated that wheelchair, another object left behind, but not one she ever thought of as hers. I see in retrospect how brave she was, moving solo and uncomplaining through mysteries of her own, and I am in awe of her resilience and stamina. She weathered loss and loneliness and traumatic upheaval, but she remembered mostly good things and tried always to be game.

She was someone who marveled at clouds or a car in candy-apple red or a cat slinking by on the sidewalk, and I realize now that her childlike enthusiasm was something rare and beautiful. Our excursions diminished in scope as her problems and limitations accumulated, but I am left with the knowledge that the simplest of pleasures can brighten someone’s day, and I am grateful for all the times I took her out for ice cream and we parked along the curb to count blackbirds on a lawn or see the jacarandas dropping blossoms like purple snow. I regret nothing except kindness withheld. What we perceived as a burden or inconvenient duty often turns out to have been a gift.

So we cleared the room of my mother’s worldly goods, and a poignant collection it was. Ninety-one years of living, and this is what she owned. It’s not a bad legacy, after all, a nice trove of wisdom, memories glinting like bright-colored glass. I don’t know if I could ever be as brave as she was, but after I pull myself together, maybe I’ll discover that I’ve inherited some of her strengths. And I’m not going to be sad. I’m going to try, as she did, to remember what was good.

People have asked me if I am the executor of my mother’s estate, and I never thought about it that way, but yes, I suppose I am. Not only that, I’m an heiress.