Haskell Wexler had eclectic tastes — grassroots unions, L.A. Lakers games, electric cars, Liberation Theology, naughty limericks, veggie food, cowboy shirts, and baseball games with Fidel Castro. We met in 1973, after he heard my NPR reports about the Indian uprising at Wounded Knee. I was a car buff at the time and was immediately taken by the fact that he had seventeen automobiles, including a 1949 Rolls Royce Silver Dawn with right-hand drive, which he’d picked up on a shoot in Italy, and a Formula 1 racer with a souped-up Buick Straight-8 engine. For the next 42 years, he was my friend and mentor.

Born into a wealthy Chicago family in 1922, Haskell took his first photos — of striking unionists during the Depression — when he was still in the 8th grade. When he was just 12 on a family vacation to Italy, he used a wind-up 16mm camera to shoot his first film. The footage intercuts tourist shots of his parents and siblings with fascist teenagers wearing Mussolini insignia. He told me that during the Spanish Civil War in 1937, when he was still in high school, he’d lied about his age to join the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Rebuffed, he proceeded to leaflet against the aerial bombings of civilians in Spain, earning him his first attention from the FBI. According to his FOIA file, the Bureau marked him as “prematurely anti-fascist.” He was 15 at the time.

Haskell enrolled at UC Berkeley in 1940. A year later, after he was expelled by the dean of students for a campus prank, he joined the merchant marines. In 1942, his ship was torpedoed by a Nazi sub off the coast of Africa. He spent two weeks in a lifeboat, nursing a leg wound, catching seagulls, eating them raw, and watching his best friend die in his arms. He was the last sailor off the sinking ship, manning — but not firing — a machine gun as his fellow crewmen scampered for safety. Haskell remembered the U-boat commander standing on the deck of the surfaced sub, shooting the bobbing lifeboat with a small movie camera. It was Friday the 13th, a day he would always consider lucky.

President Franklin Roosevelt cited Haskell for bravery in combat, but for most of his adult life Haskell would speak about the scourge of war. The day after I’d get home from assignment in Syria or Afghanistan, he’d be there on the doorstep, camera in hand, eager to know what I’d seen and heard. He wanted to know how it felt. He was interested in the detachment war photographers experience when they look through the lens, but he usually focused on the larger meaning of events. After 9/11, in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq, he noted how stocks in companies like Boeing, Raytheon, and Lockheed had skyrocketed. He remarked on the phenomenon again with the rise of ISIS, which he believed the invasion had spawned. He said it was “the marriage of capitalism and the Pentagon.”

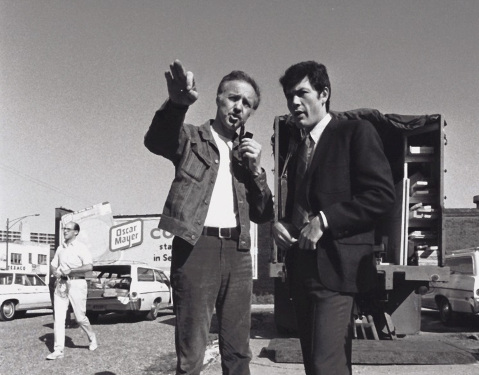

When I met Haskell in 1973, the Vietnam War was still raging. Two years earlier, he’d filmed the last interview with Salvador Allende, just before the Chilean president died in the U.S.-engineered coup. It was six years after winning his first Oscar, for Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, when he’d galloped to the stage to deliver the shortest acceptance speech in Academy history: “I hope we can use our art for peace and love.” It was five years after he’d been tear gassed at the Democratic Convention in Chicago while directing his iconic film Medium Cool and two years after his Oscar for producing Interviews with My Lai Veterans.

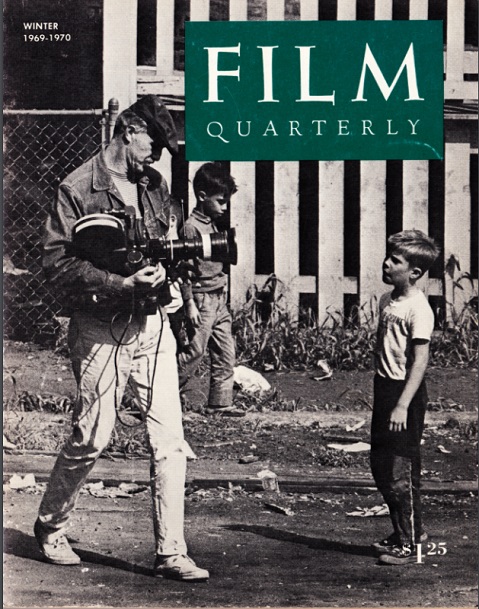

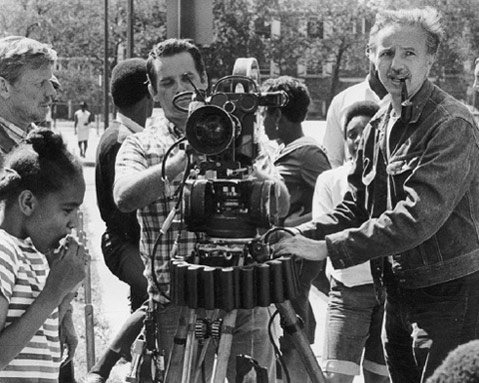

In all, Haskell would be nominated for five Academy Awards as a cinematographer, winning two. To industry colleagues, he was known for his aesthetic innovation. He was the first Director of Photography (DP) to use the Steadicam for handheld shots in a feature film. He did that in his Oscar-winning Bound for Glory, the biopic about his Merchant Marine buddy, Woody Guthrie. Garrett Brown, the inventor of the Steadicam, told me Haskell’s decision revolutionized Hollywood, giving camera operators the mobility to capture an intimacy that camera cars, track dollies, and cranes could never provide.

The legendary Steadicam moment in Bound for Glory is the shot from a crane overlooking the makeshift migrant camp the crew constructed near Stockton, California. The shot continues interrupted as the operator smoothly lands on the ground behind David Carradine (as Woody Guthrie) and follows him as he makes his way among the 900 extras playing “Okies” searching for work. This seamless, unbroken shot lasts an incredible four minutes. When the first dailies came back, the screening room was jammed with producers, crew, and the director, Hal Ashby. Brown (who also patented the Skycam, the camera robot on wires that televises football games) was there that day. When lights came up, he said, everyone jumped to their feet, roaring Haskell’s name.

But Haskell believed that filmmakers were much more than f-stops, hi-hats, focus-pullers, and Steadicams. The gear, like art itself, was just a means to an end.

The end was fighting injustice and working for nonviolent, grassroots change.

In his book, artists had a special responsibility. Not just as reflectors of culture, but as contemporary historians, even prophets. To me, that embodied W.H. Auden’s line about artists showing “an affirming flame.”

Haskell stayed in shape. Well past his 93rd birthday, he would arrive at the gym each day at 7 a.m. to work out with a trainer and to watch TV news. He preferred CSPAN — for its unedited rawness — and those broadcasts were often fodder for the commentaries that appeared on his website.

He was also an obsessive reader, which was evident in the scribbled notes that defaced the margins of nearly every book in his office. The writings of Aristotle may not have been on his shelves, but he shared the philosopher’s belief that politics was nothing less than the art of happiness. He often said he was grateful that the Oscars had given him a “soapbox” to proselytize his convictions.

Haskell shot some 60 Hollywood films and more than 100 documentaries, including Target Nicaragua, his prescient expose of the Contras and the secret CIA war in the 1980s to topple the Sandinista regime. We traveled to Nicaragua in 1982. For a scene at the U.S. Embassy in Managua, he adroitly slipped his 16mm camera past U.S. Marines at the X-ray machine to film me asking the ambassador if he was “our man in Managua.” During the same period, Haskell wrote, shot, and directed his independent feature Latino about an American soldier torn about Contra atrocities. The film received special recognition at the Cannes Film Festival, but it was subsequently pulled from distribution for poor box office returns.

Haskell asked me to shoot part of Who Needs Sleep?, his seminal expose of excessive hours in Hollywood — and the sweetheart union-producer contracts that perpetuate the risky policy. For that film, Santa Barbara director/DP Ron Dexter built a bumper rig to Haskell’s specs so the camera could show the ground-level view of a tired driver coming home from long shoots so common in the industry. But Haskell was not always one to follow his own advice. Driving home to Santa Barbara on Highway 101 from an 18-hour day on that film, he fell asleep at the wheel. He rolled his vintage El Camino near Carpinteria, but he escaped largely unscathed.

It was one of many contradictions.

Despite his belief in nonviolence, he agreed to shoot Emile de Antonio’s documentary on the militant Weathermen. That decision got him fired from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, after the FBI hounded the producers. (He was also fired by Francis Coppola on The Conversation following a dispute about lighting, although 10 years later Coppola sent him a letter of apology.)

A strict vegetarian, he drank a beer with me in Washington, D.C., when we were shooting Good Kurds, Bad Kurds. He ate fresh-caught salmon on another shoot, on the Yurok Indian reservation in Northern California. And during a film festival in Tulsa, one midnight when no restaurants were open, we repaired to a local tavern, where we split a pork (horrors) sandwich.

He was famous for shooting the Marlboro Man commercials — until public consciousness about the health risks made him turn his back on Big Tobacco. He was a safety nut but he imported Ferraris in the 1960s and personally raced a rare Lola at Riverside. When he died at 93, he still had a roll bar in his car.

Haskell often said that “the most valuable thing we own is our time,” but he seemed to give away much of his own precious time, especially to aspiring filmmakers. He was generous to my family, filming an interview with my father on his last trip to Santa Barbara; shooting my kids’ birthday parties and basketball games; flying with his wife, Rita, to the Bay Area for their graduations; visiting them as adults when they moved to New York. His message to them — and to anyone who would listen — was always the same: Be pro-people; don’t lose your history; connect the dots; build on the struggles of those who’ve gone before you.

Haskell hated hospitals. I remember one visit when he was 88. We were shooting a story about a shepherd in County Donegal, and he was chasing a sheep to get just the right shot. Suddenly, his pacemaker went haywire, and he started getting dizzy. I raced the rental car to the nearest hospital, an hour away on those twisted, narrow lanes that double for roads in Ireland. Ten minutes after nurses covered his chest with leads, the pacemaker settled down. The doctors decided to hold him overnight for more tests. Feeling “captured,” Haskell started to freak out, abruptly yanking the wires off his chest and barking a good-bye to the stunned hospital staff.

I wish he could have pulled that trick last month when he went to an L.A. hospital for the last time. But to the end, he held tight to his sovereignty and famous wit.

Rita told me that the day before he died, he informed a hospital orderly: “I’m just in here for a tune-up.” When someone with a laptop said she needed to get info “to put him into the system,” Haskell replied, “I don’t want to be part of your system.”

On his last afternoon, his sister-in-law Jane, who is a registered nurse, texted the hospital to say she’d be there just as soon as she took a shower.

“Good,” Haskell joked. “I like a clean nurse.”