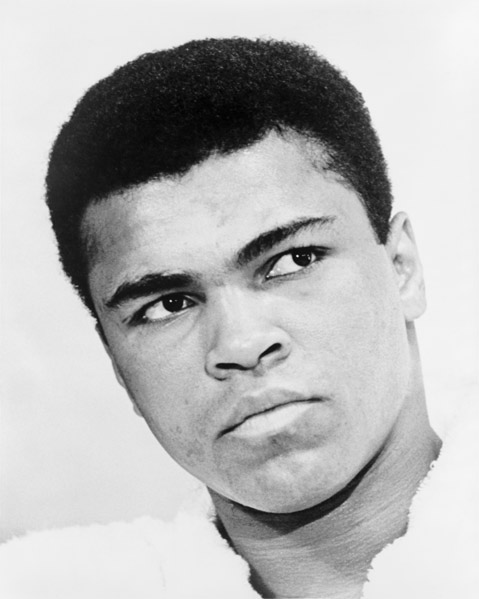

One of the most iconic photographs in sports history is of Muhammad Ali, the 23-year-old heavyweight champion of the world, roaring down at the sprawled out and defeated Sonny Liston, right arm cocked and ready to pulverize him if he gets up. That image has hung on the wall of my office forever, a great curio to my 10-year-old grandson, Eli, who asked why I called that roaring giant “The Greatest.”

In fact, news outlets from the Times of India to the Borneo Post Online; even the New York Times called him a “Titan of Boxing and the 20th Century.” From winning the Olympics to his historic fights with Frazier and Foreman, Ali, in his prime, was one of the best at any weight class in the history of boxing. But for so many, he was far more than a sports hero. For the Vietnam generation, he was a hero because he stood by his beliefs against the war and put his career and life on the line as a result.

My father was a boxing manager in Los Angeles, and we closely followed his career when he was a rising star named Cassius Clay, not yet “the man.” I saw him fight up close and personal twice at the L.A. Sports Arena — once against the aging but cagey Archie Moore.

Ali was by far one of the greatest sports publicity geniuses of all time. He was electrifying and the personification of charisma. He could promote himself and his upcoming fight like no one before or after his reign.

Before the first Sonny Liston fight, Ali mocked Liston as the “big ugly bear.” He chanted his new mantra for the world (and Liston) to hear: “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. Rumble, young man, rumble.”

With dynamic rhyming poems, accompanied by facial expressions that made you laugh, Ali may have been the world’s first rapper. He made predictions about his fights. For example, against Englishman Henry Cooper he said, “This is no jive; Cooper will go down in five.” Ali flattened Cooper in round five.

People listened and laughed, not at him but with him. After winning the heavyweight title from Liston, he shouted to the press, most of whom believed that Ali would be taken out of the arena in an ambulance: “Eat your words. I shook up the world. I’m king of the world.” No one could dispute him.

Early in his public life, he made it clear that he would be his own man. He would bow to no one. He would follow his own convictions regardless of the consequences.

At 22, after winning the heavyweight championship of the world, he announced that he was changing his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali. He had become a member of the universally disliked Nation of Islam. Few black politicians or leaders, except Dr. Martin Luther King, supported him.

Ali went from being a popular champ to being shunned by those in the boxing establishment and in the country at large. Many reporters insisted on calling him “Cassius” to denigrate his new name and religion.

Meanwhile, more Americans, many of them black, were dying in the war in Vietnam. The nation was deeply divided, and politics were toxic.

Ali became a lightning rod for those who opposed the escalating war. He told the world, “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong.” This remark became front-page news around the world. The Champ had said no to Vietnam to the cheers of many and the jeers of even more. Ali did not stop there: “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home to drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights? So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years.”

In April 1967, Ali refused to be inducted into the army. This courageous act caused boxing commissions across the country to strip Ali of his heavyweight title. He was convicted of draft evasion. A good portion of the public turned a cold shoulder to the man they once cheered in the ring. They viewed him as a traitor.

Ali was an exile in his own country. He had little to laugh about and no one to fight in the ring. He spent part of his time on college campuses delivering his antiwar message.

The Supreme Court eventually overturned his convictions, but Ali had lost three and a half years of his athletic prime. Many thought his boxing career was over, but they underestimated Ali’s iron will.

Ali came back to win 13 of his next 14 fights, including epochal battles with Joe Frazier and, in October 1974 in Zaire, Africa, against the monstrous George Foreman, who was seven years younger. After Ali knocked out Foreman, ever the showman, Ali leaned down to reporters and said, “What did I tell you?”

After his historic fights, his popularity rose again. President Ford invited him to the White House, at which he is quoted as saying, “You made a big mistake letting me come, because now I’m going after your job.”

After defending his title 10 times in the next few years, he won a technical knockout against Frazier in their final match, known as the “Thrilla in Manila.”

It was a thriller all right, but it almost killed both fighters. When Ali was asked what it was like, he said, “Close to dying.”

In the late 1970s, Ali’s doctors became concerned about his health condition and advised him to retire from boxing. Ali refused. It was only after he suffered some punishing losses in the ring that he finally retired for good in 1981.

Despite the progression of a disease that was identified as Parkinson’s syndrome in 1984, Ali did not slow down. He entered the next phase of his public career, making speeches on spirituality, peace, and tolerance and visiting diplomat missions around the world. But the ravages of the disease over the next decades deprived him of his voice — which, next to his hands, may have been his greatest asset.

But still he pushed on, raising and donating millions to charity. He made more goodwill trips around the world, where he was met with millions of admirers. He helped local children and sick children get their wishes.

He was America’s ambassador of goodwill to the world. One writer called him perhaps the most well-known person on the planet.

Then, he suddenly reappeared center stage after years out of the public spotlight to open the Atlanta Olympic Games. No one who watched Ali, his arm shaking, light the Olympic torch in the 1996 summer games will ever forget the dignity he showed the world.

In 2005, President George W. Bush, calling him the greatest boxer of all time, presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom — America’s highest civil honor — to Ali at the White House.

Sports writer Dave Zirin of the Los Angeles Times summed up the grace that was Muhammad Ali: “Ali may have seemed like he was from another world, but his greatest gift was that he gave us a simple road map to walk his path. It is not about being a world-class athlete or an impossibly beautiful and charismatic person. It is simply to stand up for what you believe in.”

And Ali did for his whole life.

Rest in peace, Great One.