Only the Ball Was White

The Bad Old Days of Professional Sports

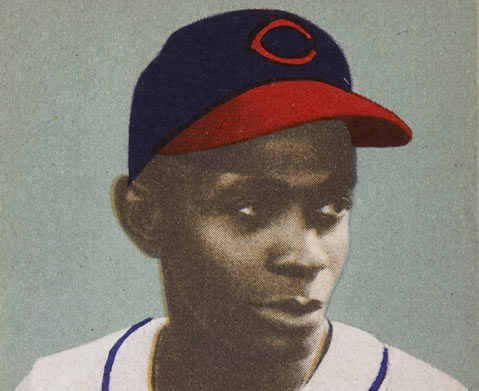

BAD OLD DAYS: Decades before Jackie Robinson donned a Brooklyn Dodgers uniform in 1947, black players were starring in professional baseball — but in the Negro Leagues.

Ironically, Robinson’s dramatic integration of the major leagues soon led to the breakup of the once-flourishing Negro National League. Other black players followed Robinson as organized-baseball owners cherry-picked the cream of the Negro League. Black fans preferred to watch their own players in major league action.

After Robinson, the Dodgers hurried to sign such Negro League players as catcher Roy Campanella and pitcher Don Newcombe. It’s a little-known story, according to David Craft’s book The Negro Leagues, that Robinson, a UCLA star, was granted a 1942 tryout by the Chicago White Sox. Manager Jimmy Dykes spoke glowingly of Robinson and other black players who tried out, but none were signed.

Robinson went into the service, played briefly in the Negro Leagues, and became a Dodger rookie at the advanced age of 28.

But if it had been up to most team owners and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who ruled baseball for 24 years, there’s no telling when the major leagues would have been integrated. Landis was dead set against it until the day he died in 1944. His replacement, A.B. “Happy” Chandler, had no such problem.

He told the press, “If a black boy can make it on Okinawa and Guadalcanal, hell, he can make it in baseball.”

The story of the Negro Leagues goes back to when interest in baseball surged after the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation may have freed the slaves, but it didn’t stop blacks from being excluded from white teams. So they formed their own clubs, and in 1885, three black teams merged to form the Cuban Giants, followed by the short-lived National Colored Base Ball League.

“To those of us who are a century removed from the pain, hurt, disrespect, and violent confrontations these men experienced because of their color, they are remembered as pioneers whose frontier was organized baseball,” Craft wrote.

But it wasn’t until 1920 that the disenfranchised players truly had a league of their own, thanks to a burly pitcher named Andrew “Rube” Foster. Foster, owner of the Chicago American Giants, formed the National Negro League.

With new teams forming and others folding, the strain was apparently too much for Foster, according to Craft. In 1926, “the father of black baseball” began acting strangely. His family moved him to a mental institution, where he died in 1930 at the age of 51.

During the Depression 1930s, teams roamed the country in broken-down old buses, slept where they could find a bed, and often were turned away at white-only restaurants or told to order at the back door.

Black stars emerged, but none more talented and colorful as Satchel Paige, master of the trick pitches who played on many a team as a hired gun. One was a semipro outfit owned by a Chrysler dealer in Bismarck, North Dakota, who signed the best players he could find, black or white.

There they were, taking on all who dared, with Paige (when he was around) throwing his assortment of fastballs, curves, blooper balls, and his famous “hesitation” pitch.

The story of “The Forgotten Team That Broke Baseball’s Color Line” is told in Tom Dunkel’s book Color Blind.

Meanwhile, major league baseball was still ignoring perhaps the sport’s greatest pitcher — until it needed him.

On July 9, 1948, Paige became the oldest man to make his major league debut. He was at least 42 when Cleveland Indians manager Lou Boudreau, fighting for the pennant, called Paige in as relief pitcher against the St. Louis Browns.

His “hesitation” pitch” caused the batter to throw his bat 40 feet. The Indians went on to the World Series and won it.

IT TAKES A LOT: Yep, it takes a lot for town and gown to come in from a perfect, warm Sunday afternoon to hear an opera soprano. But UCSB’s Campbell Hall was filled Sunday to hear Renée Fleming sing everything from Rachmaninoff to Rodgers and Hammerstein (The King and I). Leading into Patricia Barber’s “Scream,” Fleming cracked that it reminded her of “the presidential debates.” (Her appearance is thanks to UCSB Arts & Lectures.)

YO-YO MA: The world-famous cellist modestly sat in with the Silk Road Ensemble, a collaboration of international musicians, and filled the Granada Theatre for not one but two nights, also thanks to UCSB Arts & Lectures.