Ross Macdonald and Eudora Welty’s Love Letters

Correspondences from Another Time

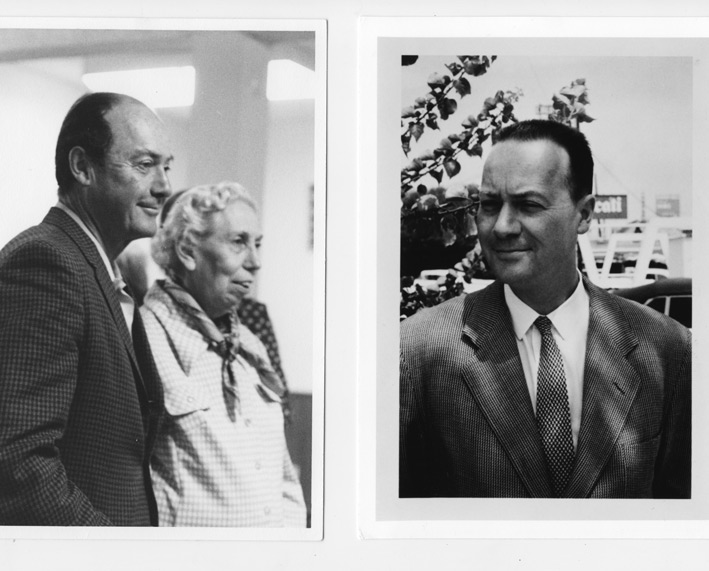

Ross Macdonald and Eudora Welty met cute in 1970. She was 61; he was 54. She lived in Jackson, Mississippi; he lived 3,000 miles away in Santa Barbara. She was single, a southern-styled Emily Dickinson who guarded her privacy with genteel ferocity. Macdonald was married to mystery writer Margaret Millar, a marriage that was famously fraught. She was soon to win a Pulitzer Prize for fiction; his novels were hailed as the apex of the American private-eye genre. Welty greatly admired his work, confessing to the New York Times how she had wanted to send Macdonald a fan letter, but thought it might seem “icky.” Reading this, Macdonald — himself a longtime admirer of Welty’s writing — answered the unsent note. That was May 3, 1970.

It wasn’t exactly love at first post, but eventually they exchanged 435 letters — urgent, tender, and passionate — over a 14-year period. These became the basis of the 2015 book Meanwhile There Are Letters: The Correspondence of Eudora Welty and Ross Macdonald, written by the authors’ two award-winning biographers, Suzanne Marrs (Welty) and Tom Nolan (Macdonald). These letters are also the focus of a new play by Irish writer Declan Hughes to be performed — as a reading — this week, courtesy of the UCSB Department of Theater and Dance’s Launch Pad program.

Spoiler alert: Welty and Macdonald never rode off into the sunset together. Over the years, they managed to get some time alone — in New York City, Santa Barbara, and Jackson — but not much and never for long. Theirs was a romance made possible by the U.S. Postal Service. Their letters are dignified, and literary, yet bursting irresistibly with loving endearments — singularly nonsalacious, yet conveying an insatiable hunger to know and be known.

Macdonald never hid the correspondence from his wife. She may not have liked it, but Maggie Millar — famously — didn’t much care for a lot of things. During one of Welty’s visits to Santa Barbara, Millar cocked her head and told Welty, “You know I read your letters to him when he’s out of town,” recounted Macdonald biographer Nolan.

Inevitably, the Macdonald-Welty correspondence has generated considerable speculation of the did-they-or-didn’t they variety. “But does it really matter?” asked the play’s director, Risa Brainin, founder of the Launch Pad program, which is intended to support new plays. Nolan, who described their relationship as “an elevated intimacy,” said, “If you read the letters you’ll get the picture. And you’ll see the beauty of the picture.”

Hughes considers Macdonald a hero, a writer who mixed sunny SoCal corruption with breathtaking landscape descriptions and intensely Freudian family convolutions. “Skeletons in closets and families sworn to secrecy about their pasts struck a real chord with me in Ireland,” he said, “where we routinely lie to others because we so regularly lie to ourselves.”

Macdonald had a painful past: His father abandoned the family, and the boy became an accomplished juvenile delinquent, experiences often reflected in his novels. His compassion for lost children also was probably informed by painful events in his married life. In the 1950s, his rebellious, suicidal daughter Linda — then 16 — plowed the car Macdonald gave her as a birthday present into three pedestrians and another car. She was drunk and ran from the scene. A 13-year old boy was killed. The ensuing Santa Barbara trial was ugly. Linda got off with probation. Some sympathized. Most were outraged. A few years later, Linda — struggling with mental illness — disappeared, giving rise to a nationally publicized manhunt. Macdonald, née Ken Millar, donned the identity of his literary action hero, Lew Archer, and joined the search.

By the time Welty and Macdonald started their pen-pal courtship, Linda’s life had calmed down. She was married and had a young son. Then Linda had a sudden stroke and died. Macdonald shared his grief with Welty. “I am willing now to grow old and die,” he wrote her in December 1970. Welty, having buried both parents and her brother, opened her heart. The literary courtship began.

They wrote about birds, politics, oil spills, Richard Nixon. They wrote about other writers. While massively supportive and always encouraging, they quietly made suggestions about each other’s works-in-progress. Tom Nolan recalled phrases from her letters: “Please dear take care of yourself: I think about you every day wherever we are, you know that: you are in my thoughts and dear to my heart; every day of my life I think of you with love.”

They first met in New York City, at that literary mecca, the Algonquin Hotel. Neither knew the other was there, but, it turned out, they were in rooms across the hall from each other. On three occasions, Welty visited Santa Barbara. On the first trip, Macdonald met her at the airport and took her immediately to the ocean. He took her to the Coral Casino, to the Biltmore, and to the Santa Barbara writers’ luncheon held once a month at La Arcada in downtown Santa Barbara. “That was a big deal, because women were not permitted there,” Nolan said. “He broke the rule.” Maggie Millar, Nolan said, “would have thought it was a big waste of time.”

Often asked why Macdonald didn’t leave Millar for Welty, Nolan said, “It’s unthinkable given the person he was.” He cared for her when she went blind in one eye and struggled with lung cancer. Welty worried about what toll that took on Macdonald. As Maggie recovered, Macdonald’s memory started to unravel. It was Alzheimer’s. Millar cared for him also, but was impatient. Welty became the only person to whom he confided his fears. She then wrote a story about a woman who takes solace in her own forgetfulness because it’s something she can share with her beloved. “That just gets me every time,” Nolan said. Two years before his death in 1983, Macdonald stopped writing.

Translating letters into a play with story line and characters is always a challenge, and in this case the eloquence of the raw material makes it more daunting. Hughes and Brainin are still working out the last details. Next week, the three actors will run through a four-hour rehearsal. The performance is a reading, not a play. There will be no lighting, no costumes, no sets. If it ever makes it to Broadway, the hope, said Brainin, is that next week’s audiences can say, “I saw it first here.” She added with a laugh, “You have to think big.”

4•1•1

Readings are on Thursday, August 10, at 7:30 p.m. at the UCSB Studio Theater, and Friday, August 11, at 7 p.m. at the Community Arts Workshop (631 Garden St.)