Does Bellosguardo Now Belong to Santa Barbara?

Silence and Secrecy Continue to Cloak Clark Estate

It appears the long-awaited transfer is complete of the late Huguette Clark’s Bellosguardo estate from legal limbo in New York to a Santa Barbara nonprofit created to manage the 23-acre property as a public space for the arts. But what was expected to be an exciting announcement after three years of unanswered questions about the fate of the mysterious mansion above East Beach has instead become a matter of intense silence and secrecy.

The Santa Barbara–based Bellosguardo Foundation was formed in 2014 as part of a settlement agreement of Clark’s will, after the reclusive heiress to a copper fortune died in 2011 at age 104. Though she owned other valuable properties ― including an estate in Connecticut and two luxury apartments in Manhattan ― Bellosguardo was her West Coast legacy. According to the settlement, which was administered by the Attorney General of New York, seven of the 10 initial members of the Bellosguardo board were nominated by Santa Barbara Mayor Helene Schneider, who at the time described the foundation’s primary mission as “to open the Bellosguardo house and gardens to the public as a center that will foster and promote the arts.”

That goal stalled hard in probate court as the board awaited a decision by the IRS whether to waive $16 million to $18 million in gift tax penalties owed by Clark at the time of her death. A decision earlier this month by Santa Barbara Judge Colleen Sterne, however, accompanied by court documents filed in November, suggests the penalties have been forgiven and that management of Bellosguardo has officially moved from the New York County Public Administrator’s Office to the foundation.

A “Petition for Final Distribution” filed in Santa Barbara Superior Court on November 11, and approved by Sterne sometime before a December 14 hearing date, says the Clark estate owes no personal income or property taxes, either state or federal. It dictates that all $95 million of Bellosguardo assets, which include the mansion itself, a large collection of paintings and sculptures, a $1.7 million doll collection, and $4.5 million in cash, be transferred to the foundation. A copy of the petition can be found at the bottom of this article.

Final confirmation of Sterne’s ruling, however, has been difficult to obtain. Neither attorney representing the New York Public Administrator in court, Gamble Parks in Santa Barbara and Peter Schram in New York, returned requests for comment. Questions posed directly to the Bellosguardo Foundation’s boardmembers over the last four weeks were referred to executive director Jeremy Lindaman, who has repeatedly declined to comment. “This is a complicated issue with a lot of moving parts,” he said. “I’ve been asked to refer questions regarding the petition to the New York Public Administrator.” Multiple calls and emails placed to the Administrator’s Office were never answered.

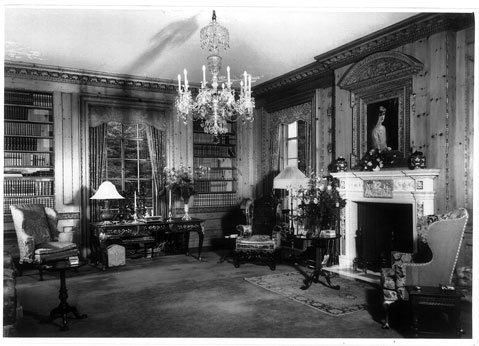

Also unclear are details of any plan to convert the sprawling and austere 27-room property into a public space for the arts. The mansion has sat vacant since the 1950s, except for a small team of caretakers and groundskeepers, and is saddled with $12 million in deferred maintenance. Monthly upkeep alone costs a reported $40,000.

In its three years of existence, the foundation has yet to publicly present a budget or describe any operational strategies, including for public access, show programming, personnel and payroll, endowment options, or other income sources. Doubts have been raised among Santa Barbara’s arts and nonprofit leaders that transforming Bellosguardo from a 1930s poured-concrete castle to an inviting arts haven is a tenable endeavor. The term “money pit” has been used more than once. (Read a first-hand description of the building and grounds, as well as a full analysis of Bellosguardo’s challenges, by Independent arts editor Charles Donelan after he was granted an exclusive tour of the property. Donelan writes more about Clark’s strange life and vast art collection here.)

Similarly left unanswered at the moment are questions around the fate of seven Bellosguardo employees, who were at risk of losing their jobs in the transfer. Longtime resident manager John Douglas sent a letter on November 19 to the foundation’s boardmembers, reminding them that his and his colleagues’ employment would be terminated as a stipulation of the handoff and asking that the board intervene before the petition was finalized. “As the resident manager of Bellosguardo for over 35 years, I have been a loyal, diligent, and honorable employee,” he wrote. “I have also lived at Bellosguardo for all of those 35 years, so it is much more to me than just a place of employment ― it is also my much loved home. There is not a building, system (plumbing, electrical, security, fire-safety, structural), tree, bush, or even blade of grass at Bellosguardo that has not been thoughtfully administered to under my supervision and tutelage during the last three decades.”

Douglas described his “amazing team” of six employees, “who assist with landscape maintenance, bookkeeping, and maintenance,” and implored the board to act “quickly and expeditiously” to save their jobs. He said he had yet to be informed of the foundation’s plans even as the deadline, the December 14 hearing date, approached. “Ms. Clark would be profoundly dismayed and saddened had she known that I, and the other employees at Bellosguardo, would face this sort of stress at a time when she was expecting her legacy to become even more firmly established ― as her final gift to Santa Barbara.” Douglas did not respond to requests this week for further comment. A copy of his letter can also be found below this article.

Public statements and financial disclosure documents provide some insight into the foundation’s activities over the last three years, but they’ve also raised concern among individuals involved early in the nonprofit’s formation. Those concerns revolve chiefly around executive director Jeremy Lindaman, the longtime political consultant and personal confidant of Mayor Helene Schneider.

Soon after Schneider nominated members to the Bellosguardo board, who were all ultimately approved by the New York attorney general’s office, Lindaman was brought on to lead the foundation. It remains vague how exactly he was hired. Schneider claimed in a January 2015 Noozhawk article that she was not involved in the board’s staffing decisions, though Lindaman also stated in the same report that Schneider initially requested his help giving tours of the property and was then asked by the board to remain involved during the transfer.

In a separate October 2017 Noozhawk article, boardmember James Hurley, who was Clark’s personal attorney for many years, said he had no knowledge of Lindaman’s hiring. “I have no idea how he even got in the picture,” he said. Hurley also stated at the time ― just two months before the December 14 probate court date ― that he was unaware if any progress had been made in approving the transfer petition. “I don’t know a thing even though I’m on the board,” he told Noozhawk, explaining the board had met only three times in more than three years, most recently six or seven months ago.

Hurley did not respond to the Independent’s requests for an interview. Some boardmembers spoke privately with the Independent about their confusion and displeasure with Lindaman’s position, and how he obtained it. Others were surprised to hear Lindaman is collecting a yearly salary, and they questioned what he had accomplished in his time as director.

According to the Bellosguardo Foundation’s records for tax years 2015 and 2016, Lindaman collected $110,000 and $80,000 in salary, respectively, working 10 hours a week. Very little comparative income was reported. The 2015 record shows the estate of Huguette Clark, through the New York Public Administrator, contributed $150,000 to the foundation. In 2016, the estate gave another $30,000.

Board chair Dick Wolf contributed $50,000 and board secretary Sandi Nicholson gave $5,000. The WWW Foundation, an arm of the Whittier Trust, a South Pasadena wealth management firm, also donated $20,000. Several WWW Foundation boardmembers live in Santa Barbara, a Whittier spokesperson said. Wolf could not be reached for comment.