Mass Deportations Echo Ellwood Attack and Prison Camps

Santa Barbara DA Accelerated Japanese Roundup

LOCK ’EM UP: As a general rule, anniversary-event story assignments are to be shunned at all costs. Such articles, unfailingly worthy, are almost always dull, involving events that happened too long ago.

This week, I’m making an exception.

Seventy-five years ago on February 23, 1942, a Japanese military submarine the size of a football field — with both end zones attached — celebrated the national holiday commemorating George Washington’s 210th birthday by bombarding Goleta’s Ellwood Beach with 83-pound armor-piercing missiles for about 25 unmolested minutes. As such, this attack was the first official act of war conducted by a foreign power that had hit the continental United States since the British invaded Washington, D.C., in 1812.

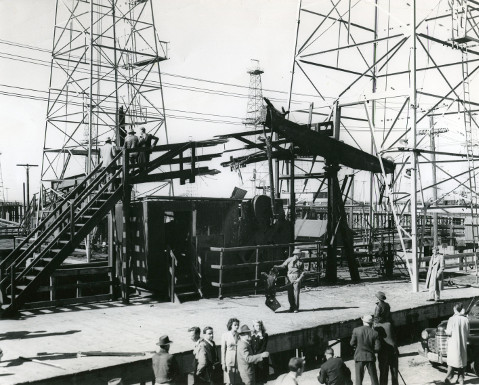

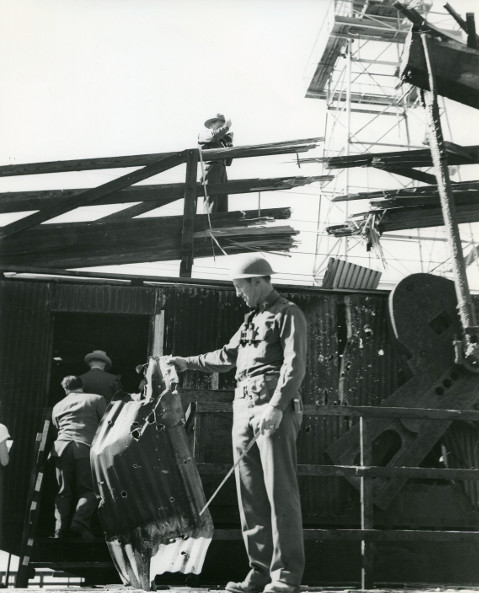

The good news was that most of the shells — about 25 were fired — were duds. A wooden pier used by the oil companies operating at Ellwood sustained nonfatal wounds. An oil industry support shed was shredded. The real target — two 80,000-gallon tanks of exceptionally explosive airplane fuel perched on the bluffs — were miraculously missed. Aside from horses in nearby fields, who reportedly went mad from the explosions — screaming and running — no real damage was done. The police, responding after the fact by blasting out the lights of any downtown shop, storefront, or restaurant that happened to be violating wartime blackout rules, did far worse.

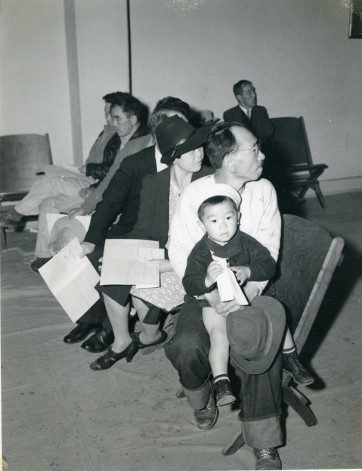

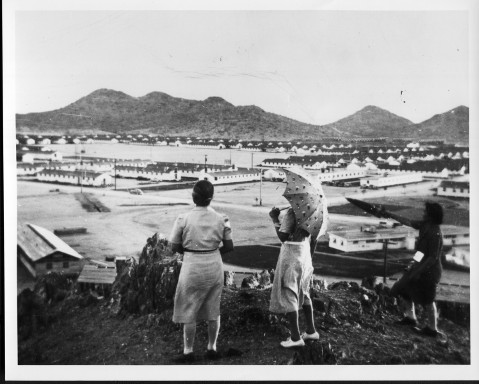

Just four days before in the same year, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the now infamous Executive Order 9066. Although this order made no specific mention of the Japanese or Japanese Americans then living along the Pacific Coast, it led to the detention, forced evacuation, and incarceration — barbed wire, armed guards — of 110,000-120,000 American-born citizens whose criminal conduct was being of Japanese descent. In Santa Barbara County, that was about 2,200 people. No charges were filed. No trials held. No evidence brought. No one given a chance to defend themselves.

Most of those interned spent about three years behind the concertina-wire curtain in what Santa Barbara’s congressmember at the time, Alfred Elliott, approvingly described as “concentration camps.” In a speech on the House floor, Elliott urged “moving the Japs in California” into these camps “damn quick,” adding, “ … and don’t let someone tell you there are good Japs.”

Such racism notwithstanding, the story of the Ellwood shelling has been told so many times it now qualifies as “local lore,” quaint, quirky, and colorful. But no, as a matter of historical fact, the skipper had never been to Santa Barbara before — as is often reported. And no, the attack was not inspired by some humiliation he endured at the hands of Ellwood oil workers after falling into a cactus patch with a camera — those Japanese and their comical fixation with cameras! — strapped around his neck. (It is worth noting, however, that the Ellwood oil fields were highly instrumental in fueling the imperial Japanese throughout the 1930s as Japan pursued predatory expansionist policies that gave rise eventually to World War II.)

THIS YEAR IS DIFFERENT This year, it’s serious. That’s because of what’s happening under the new presidency of Donald Trump. Like Roosevelt’s executive order against the Japanese, Trump’s proposed refugee ban — blocked successfully so far in the courts on strictly procedural grounds — made no mention of its true target population: Muslims. Add into this mix the “mass deportations” that the Department of Homeland Security absolutely insists are not about to happen. Whatever lipstick one chooses to apply to this particular pig, the department needs to hire 10,000 new immigration officers to put a whole lot of people behind bars for eventual deportation.

Civil liberties?

Based on our experience with fear-mongering, crackdowns, and roundups with Ellwood and the Japanese internment, we can safely say, “Been there, done that.”

Although the Ellwood shelling took place four days after Executive Order 9066 was signed into law, it had everything to do with how the vaguely worded order would eventually be enforced. As originally envisioned, the executive order called for voluntary evacuations from the Pacific Coast to inoculate the region against any potential threats posed by fifth columnists, spies, and saboteurs lurking among the Japanese populations. After Ellwood, what had initially been voluntary quickly became mandatory.

Given this connection, many have wondered over the years whether Ellwood was a put-up job. Fueling such suspicion, U.S. Navy planes stationed at the Goleta airport were ordered down the night of the 23rd. Just the day before, the only big artillery gun in Santa Barbara — on loan from a garrison in Los Angeles — had been returned. The shelling commenced just as President Roosevelt had launched into one of his famous fireside chats, this one on the vulnerability of the coast to Japanese attack. This — coupled with the utter lack of military response to the sub attack — made many worry, at the time, that Roosevelt orchestrated the whole thing to create a pseudo wartime emergency needed to justify an executive power grab.

Such conspiratorial concerns, however tempting, do not hold up to scrutiny. The documented historical record — impressively buttressed by the 2000 UC Berkeley thesis of Kent Haldan and the 2010 UCSB thesis by Ken Hough, from whom I have begged, borrowed, and stolen — indicates the Japanese I-17 sub, a submarine aircraft carrier, attacked Ellwood, a safely unguarded and remote target, to show the United States Japan could penetrate its perimeter. It appears timed to coincide with Roosevelt’s speech.

What’s missing from the conventional Ellwood lore is the extent to which Santa Barbara elected officials played significant, albeit subsidiary, roles stirring the pot in favor of the indiscriminate, round-’em-up approach to the Japanese. In hindsight, Santa Barbara — Santa Maria and Guadalupe to be more precise — can be regarded as the ladle by which that pot got stirred.

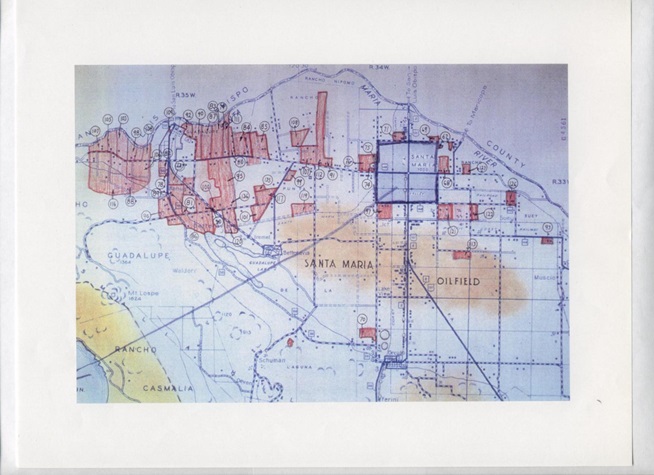

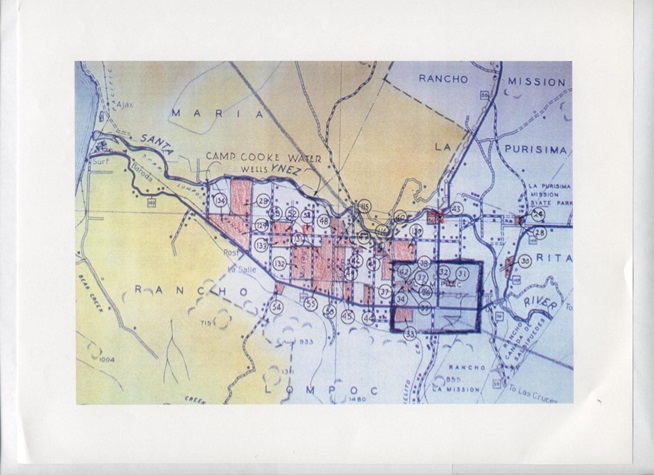

RIGHT MAP, WRONG FACTS: In fact, it would be Santa Barbara’s then-DA, Percy Heckendorf, who would produce the key damning document that would emerge as Exhibit A in the battle for mandatory internment. This document was a map of key infrastructure vulnerable to “Jap attack” throughout Santa Barbara County: oil refineries, railroad bridges, military installations, lighthouses, reservoirs. Living perilously close to all these installations, Heckendorf found, were clusters of Japanese farmers, any one of whom, he fretted, could be a fifth columnist. Heckendorf fed this information to his close friend Earl Warren, then California’s powerful attorney general, who was running — successfully it turned out — for state governor. Heckendorf would say, “The whole area is surrounded by Japs.” More subdued but equally insistent, Warren would argue, “It would seem difficult … to explain the situation in Santa Barbara County by coincidence alone.”

Warren cited Heckendorf’s maps to secure support for mandatory evacuation by an association of California law enforcement executives. He used them to win support from the U.S. attorney general, who was exceptionally dubious such measures were needed. And he used them with devastating effectiveness when testifying before a congressional subcommittee on wartime preparedness. While Heckendorf lacked Warren’s stature and clout, he used the maps to bend the ear of nationally syndicated columnist Walter Lippmann, whose influence is hard to exaggerate and whom he happened to bump into at a Montecito party. Two days later, Lippmann wrote the first of two columns advocating forced evacuation. A few days after that, the executive order was signed.

Two years later, Heckendorf’s evidence was directly alluded to when the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of forced internment of 110,000-120,000 people without any due process. That Supreme Court ruling was the sole basis for the claim made by Trump supporter and former Navy SEAL Carl Higbie on Fox News last November that a proposed Muslim registry could pass constitutional muster. “We did it during WWII with the Japanese,” Higbie famously declared.

He’s right. That Supreme Court ruling has never been overturned.

What Heckendorf missed is that the Japanese were there way before the oil processing plant or military base — Camp Cook, Vandenberg’s predecessor — were ever built, basically creating the backbone for what’s become Santa Barbara’s berry-based ag industry. No acts of espionage or sabotage by any of these “Japs” have been documented. That they were deemed guilty by virtue of their race is irrefutable. “The Japanese race is an enemy race,” declared General John DeWitt, charged with executing the mass roundup. “And while many second- and third-generation Japanese born on United States soil, possessed of United States citizenship, have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial stains are undiluted.” When DeWitt would be later called on the congressional carpet to defend the mass evacuation, the only evidence he could cite was the Ellwood shelling.

Toru Miyoshi, who would serve with distinction as a county supervisor, was 13 when his family was uprooted and 17 when he returned home to Santa Maria. Miyoshi and his two brothers — both of whom served in the military during WWII — would forge screamingly successful careers. His mother would have a stroke in the camp. Before internment, Miyoshi’s father ran a thriving general store in downtown Santa Maria. After his return, he worked as farm laborer. Although Miyoshi’s father never ever “bitched about” it, a price had been paid.

Warren would go on to be a great governor and even greater Supreme Court chief justice. Only in memoirs published after his death did Warren ever express “deep regret.” In 1976, then-president Gerald Ford — a card-carrying Republican — would publically apologize, saying the price had been too high and that the mass incarceration had been unwarranted. In 1988, Ronald Reagan — hardly a knee-jerk civil libertarian — would sign a congressional bill declaring the internment a race-based disgrace and offering limited reparations — $20,000 — to any surviving internees.

Like I say, been there, done that.

Happy Presidents’ Day.