Refrigerators and Climate Change

HFCs and How Coolants Are Changing Our Atmosphere

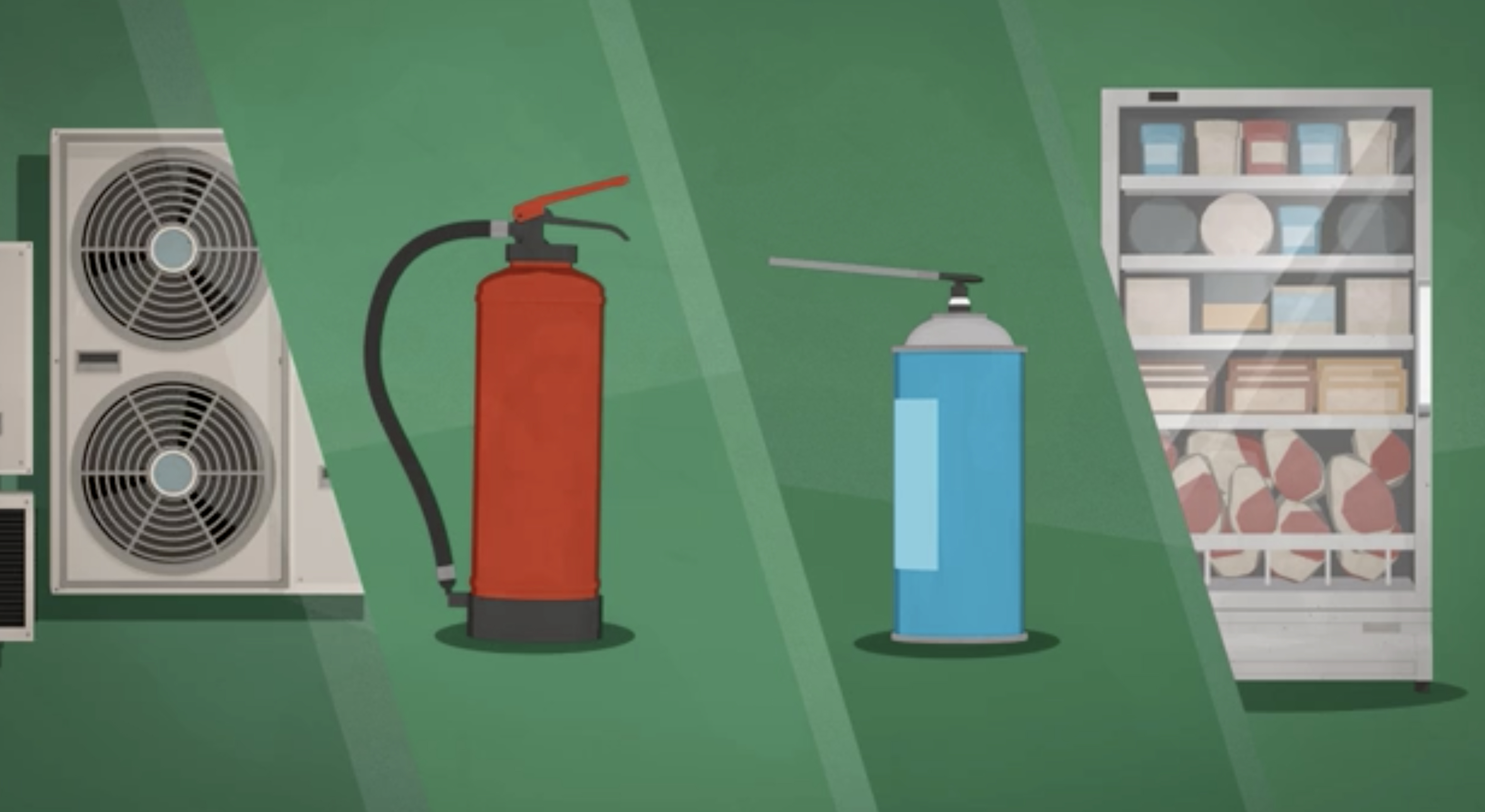

Refrigerators are a normal part of our lives. Similarly, 86 percent of homes in America have air conditioning. The link between these two is the refrigerant used, primarily hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). HFCs became the dominant coolant following the 1987 Montreal Protocol, a global agreement that phased out the prevalent chemical refrigerants in use at that time — ones that were destroying the planet’s ozone layer.

Although HFCs have no deleterious effect on the ozone layer, they warm the atmosphere 1,000-9,000 times more than carbon dioxide, depending on the exact chemical composition. Even though they make up only a small percentage of greenhouse gases, the powerful heat-trapping properties of HFCs created the urgency that led to an agreement last October to replace them.

After seven years of turbulent negotiations, most of the world’s nations agreed to a compromise amendment to the Montreal accord: The richest countries will freeze production and consumption of HFCs by 2018; much of the rest of the world, including China, Brazil and all of Africa, will do the same by 2024; and a few of the world’s hottest countries, including India, Pakistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, will have the most lenient schedule, with a target date of 2028.

Compared to the Paris Agreement of December 2015, this climate agreement has received little fanfare. Yet its impact will be equal to or greater than that of the heralded Paris accord: It is binding rather than voluntary like the Paris document. Moreover, scientists estimate it will reduce global warming by about one degree Fahrenheit, a truly major achievement.

There is some concern that the replacement chemicals, some of which are already being manufactured, may not achieve the goals set forth in the agreement. Some of the new coolants are attempting to balance warming potential with higher energy efficiency. One of the reasons that India and other countries in the 2028 grouping pushed for delays is that their people are on the verge of being able to afford air conditioners powered by HFCs. The new options tend to be more expensive. A big dilemma of global warming is that the means of keeping us cool make warming worse.

Refrigerants cause emissions, namely leaks, throughout their life cycle — during production, when being serviced and at time of disposal. If handled with care and stored at the end of their cycle, they can be purified for reuse or processed into other chemicals that don’t cause warming. Unfortunately, these procedures augment costs.

We are coming to understand that the answer to global warming lies not in one grand strategy but in moving forward with many measures deploying a variety of approaches and technologies.