Tough Urchins and Future Fisheries

Can UCSB Scientists Help 'Climate-Proof' Important Seafoods?

When it comes to figuring out how sea life can adapt to a rapidly changing climate, scientists may have a lot to learn from urchins. Turns out, sea urchins are pretty tough. These spiky echinoderms may not be as cute as a floatation of otters or as cool as flowing forests of kelp, but they may hold critical clues as to how commercial fisheries and aquaculture operations might contend with a warming world.

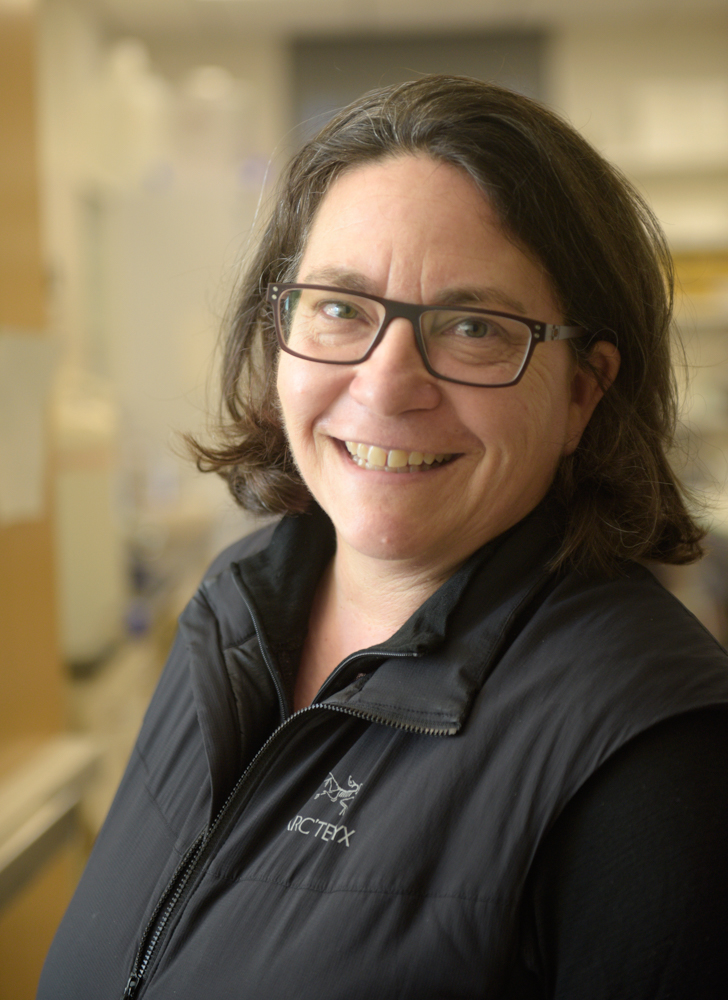

“Tough urchins tend to make tough babies,” according to Gretchen Hofmann, a UCSB molecular ecologist who focuses on the response of marine organisms to a changing environment. In this context, she explained, “tough” means able to tolerate warmer water. “If these animals can change quickly to persist in warming environments, it could help us understand how entire communities might be able to change. The thinking is that some organisms will be good at dealing with the heat while others won’t.”

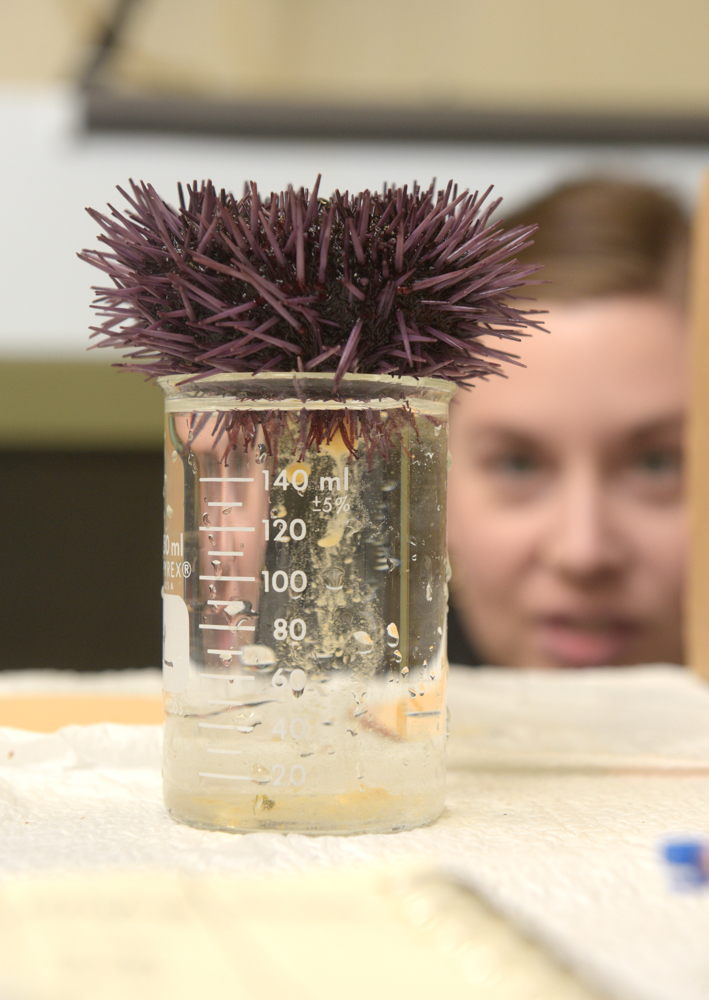

At the Hofmann Lab last week, postdoctoral researcher Marie Strader explained that she and her fellow scientists were studying urchins — some in tanks simulating a normal ocean, and others in more acidic conditions associated with water that’s absorbed a lot of carbon dioxide, that greenhouse gas linked to global warming. After inducing the urchins to spawn (with a diluted solution of potassium chloride), Strader said, gathered gametes (eggs) are gently blended with sperm, and the progeny are studied.

“We’re mimicking climate change in the lab,” said Hofmann. “We’re asking: If the adults experience an environment that’s a little more challenging, will those females imbue things into the eggs that make their babies tougher? We test the progeny — are you bigger? Do you have more lipids? Did your mom pack you a better sandwich? There’s a lot of theory and a lot of data that says animals kind of naturally do this, but we’ve never looked this carefully and in a climate-change context.”

The applications are real, Hofmann added. “Can we save a fishery by raising heat-tolerant red urchins? The idea of ‘climate-proofing’ aquaculture is incredibly important globally.” The commercially harvested urchins that injected an estimated $30 million into Santa Barbara’s economy last year range from Baja to Alaska. Urchin roe, or uni — the Japanese word for “delicacy” — is an acquired taste; most of the harvest is exported. But they’re easier to study in the lab than a food stable from the depths, such as black cod, for example. “You have to start somewhere,” Hofmann said.

The Hofmann Lab is also taking a hard look at the Santa Barbara Channel’s iconic kelp forests, those fast-growing undersea amber realms where all kinds of plants and animals gather, feed, and breed. “Kelp forests are more than just great places to be a fish,” Hofmann said. “They actually change the nature of the water. They put in more oxygen, and because they do photosynthesis, they suck CO2 out of the water, making it less acidic and providing this great climate change protection service.”

But kelp forests, which also range from northern Baja to Alaska, don’t thrive in warmer water. “Maybe there is a threshold,” Hofmann wonders about that temperature at which thinning kelp forests can no longer render services critical to all the forms of life they support. But right now, she added, “We’re not there yet.”