The Ecology of Fire

ready to burn again?

“With attention to the widespread damage which results to the public from the burning of the fields, customary up to now among both Christian and Gentile Indians in this country, whose childishness has been unduly tolerated, and as a consequence of various complaints that I have had of such abuse, I see myself required to have the foresight to prohibit for the future… all kinds of burning, not only in the vicinity of the towns but even at the most remote distances….Therefore I order and command all commandantes of the presidios in my charge to do their duty and watch with the greatest earnestness to take whatever measures they may consider requisite and necessary to uproot this very harmful practice of setting fire to pasture lands ….“

May 31, 1793 – Jose Joaquin de Arrillaga

THE WIND STARTS in the dry heat of the Great Basin. In the air above Utah, a zone of high pressure begins to build. Simultaneously, a band of low pressure begins to develop on the western side of the mountain ranges, sucking the wind towards the Sierras. As it sweeps across the desert floor it is heated by compression. Increasing in speed, it races across the Central Valley, through Santa Barbara County, and over the crest of the Santa Ynez Mountains, funnelling down into the city as a searing heat that raises temperatures rapidly towards a flash point.

On the day of the fire the wind is hot and dry, increasing steadily throughout the afternoon until it becomes a gale, filling the air with dust devils, bits of plant material and an oven-like heat. In the chaparral, with precious little moisture in its system, the leaves begin a death-curl, many of them dropping off.

By 4 pm the temperature has risen to 108 degrees; by 8 pm that evening it has fallen only 6 degrees-a pattern that has been repeated on the previous three days. By September 24, the tinder-dry brush is ready to explode. A careless fire in the Santa Ynez drainage ignites this Santa Barbara wildfire.

Steadily it creeps up the north side of the mountains, cresting them as the wind builds in velocity. That evening town residents witness an incredible fireworks display. “No Fourth of July celebration could compare with this,” the Santa Barbara Morning Press reports. “The fire came down the mountainside with the speed of a horse; and soon the mountain seemed a vast furnace painting the heavens with its lurid crimson hues.

“The awful roar of the voracious element, plainly heard a distance of five miles, the sheet of flames sweeping along the mountainside and leaping high in the air, the immense volumes of black smoke rolling skyward, rendered the scene grand and appalling.”

For several days the fire burns, at times threatening ranches and associated structures, though sparing the city. Gradually, as the high pressure shifts, and the intense winds dwindle, the fire lays down.

This is not the 1980s or 1990s-the year is 1885. It is is not an isolated event, but part of a larger pattern; fire is a natural part of the Santa Barbara landscape and has been for the last several million years, a fact, curiously that we have not really understood until recently.

WHAT IS IT that makes for such fires? Simply put, it is chaparral plus wind plus people. As I sit here at my computer writing these words, staring out my window at a magnificent view of an oak forest, chaparral hillsides, Figueroa Mountain in the distance, the fact that fire is an overwhelming necessity is not something that is immediately comforting. I have chosen to live in the midst of this fire-prone land.

The view is private and the feeling is special. The mountains are my home and I would live nowhere else. In an area that is becoming increasingly crowded, the mountains are my retreat, the place I like to call my home.

My feelings are something like those of Roger Horton, whose house is destroyed in the Sycamore Fire. “I lived here so long,” he says, “the possibility of a natural disaster has become pretty deeply ingrained with me. In a short period of time we had an oil spill, an earthquake, floods, and three major fires. I knew by living here disaster was a possibility. I never had the sense that fate dealt me an evil blow. I knew it could happen.”

Like Roger and the chaparral plants, I have adapted.

*************************************

If there is a characteristic which seems to mark this country, it is a sameness-there is little here to differentiate one mountainside or plant community from another. Even in its most colorful months during the springtime, the mountain wall behind Santa Barbara is remarkably dull-both in character and color-looking the same today perhaps, as it did to the Chumash 5,000 years earlier. Despite this appearance, it is nevertheless a land of inherent instability

It is a region still governed by the great forces of nature, a land of deep time, events occurring at a geologic pace. The history of these mountains dates back perhaps 250 million years when the movement of gigantic tectonic plates caused the shifting of entire continents and the breakup of what was then Pangaea. Built upon a succession of marine layers-sands, siltstones, and clay-they have been thrust skyward by tectonic movement measured not in generations but in the thousands of years.

Forming a continuous crest from Ojai to Gaviota, the Santa Ynez Mountains are steeply tilted to the south at an angle of nearly 50 degrees. At one point in their geologic history they have been as much as 7,000 feet in elevation. In the intervening period since Pleistocene mountain-building processes dominated, erosion has taken its toll. The Lookout Tower atop La Cumbre Peak today is at 3,985 feet.

If the collision of the huge tectonic plates has forced the Santa Ynez Mountains steeply into the air, water and gravity have worn deep canyons into the mountainous faces, forming a series of vertical headwalls and narrow chasms.

The vegetation which clothes the mountain wall has responded to this instability well. While the land changes, the chaparral remains as a constant. What is seen from the valley floor is more a coating of outer clothes than the plants themselves. The life force is in its burl, where nutrients are stored, and in its long tap root, which reaches deeply into the recesses of the sandstone to gain enough moisture for survival. Remove the outer clothing and the plant responds with a surprising vitality. Chaparral dominates where mountain-building and erosive forces are at work, not because the plants are long living, but because they have adapted to this instability, and are able to regenerate quickly. Maturity for the chaparral is measured in cycles rarely longer than twenty-five or thirty years.

Seldom more than fifteen feet in height, the chaparral is an elfin forest named after the chaparro, a scrub oak that grows in Spain. Though lacking in stature, el chaparro makes up for it in orneriness. There is a delicate aroma to the chaparral, the sweet-smelling oils in its leaves adapting it well to fire. This causes a curious juxtaposition of opposites-of toughness and delicacy-which marks chaparral country.

Though not so easily distinguished in a casual glance, properly speaking, there are two distinct elements to the chaparral: coastal sage; and hard chaparral. Coastal sage is rarely found above 1,500 feet in elevation and is composed of low herbaceous shrubs, rarely more than seven feet tall, and are found along the lower foothills. The hard chaparral is found in the higher elevations and is composed of the duller green plants such as chamise, manzanita, scrub oak and ceanothus that give the mountain wall its characteristic color. Despite the less-than-appealing aesthetics of these plants, they are well adapted. Poor soil, lack of water, and intense summer heat would kill off any other plant community, but in a Darwinian sort of way there is a grace to their ability to survive in such conditions.

Survival is due to their sclerophyllous nature, which means they have characteristics allowing them to resist water loss. For the scrub oak this means a heavy wax cuticle on the leaves and stems; those of the manzanita are tough and leathery. Others have extremely small leaves like the ceanothus, barely a quarter inch across, or the chamise, whose leaves are equally tiny and needle-like.

Its main adaptation, however, is to fire, which initiates a new cycle of plant succession. In the hard chaparral the buildup of dead fuel serves to ensure the continuity of fire; in the coastal sage it is the volatile and highly flammable oils which do so.

Viewed on a linear scale, the chaparral life cycle can be seen as a series of pulses, each initiated by fire. Removal of the older brush by wildfire is not an adversity that must be overcome but a biological necessity.

Before the Chumash appear along the South Coast perhaps 10,000 years ago, lightning has been the chief cause of fire. If core samples taken from the Santa Barbara Channel are indicative, large wildfires have raged through the area on the average of every 66 years.

What happens if it doesn’t burn? In the early 1900s the predominant belief is that the chaparral has resulted from man’s careless introduction of fire into the Southern California landscape. Scientists theorize that pine forests have once been the dominant community, and that by eliminating fire, they can be restored to their former glory. Suppression of each and every wildfire becomes the official State and Forest Service policy and in the 1930s, hundreds of thousands of pines are planted by Depression crews, more than 30,000 of these trees in the Santa Ynez Mountains.

Most of the pines die, a few of them remaining on the cooler, more moist slopes of La Cumbre Peak as a reminder. The chaparral does not die back as theorized. Later, it is discovered that the chaparral, when fire is withheld, progressively turns to dead, woody material until, by age 30, as much as 90 per cent of the plant may be composed of dry fuel.

This is known as fuel loading and because of this policy of fire suppression, by the 1950s each 1000 acres of chaparral on the front side of the Santa Ynez Mountains has a fuel loading that is the heat equivalent of a Hiroshima-type atomic bomb. From 1955 to 1971, in three major wildfires which burn the entire length of these mountains from Refugio to Casitas Pass, more than 160,000 acres of chaparral are consumed.

This first element of fire-the chaparral-is for the Forest Service a cause of intense frustration. If they eep it from burning, all they’ve done is to create the conditions for a major wildfire. If they burn it in a safe manner-which probably can’t be done near the edge of civilization-thirty years later the chaparral returns, like the little girl in the popular horror movie, saying, “I’m baa-aaaa-acck.”

*************************************

By the 1980s lightning-caused wildfires, nature’s way of igniting the chaparral, are the exception, not the rule. After almost two hundred years of efforts to the contrary, the policy of excluding fire from the hills has done the opposite of what has been desired; there are far fewer small fires, but those which do occur burn even larger, and are much more destructive than those which once occurred in pre-historic times.

Thus the paradox of wildfire: the exercise of extreme vigilance during periods of high fire danger, and prompt suppression of fires while still small may be successful in the short term; but over the long term, it is always done at the expense of storing up a tinderbox of material for future fires.

“The longer an area remains unburned, the greater becomes its potentiality for fires of uncontrollable fury,” a UCSB Professor of Biological Sciences warns in the late 1960s. “The reason is simple. In our very dry climate, the accumulation of combustible debris becomes thicker with each passing year and as the fuel accumulates, the difficulty of quenching a fire also mounts.”

In the 1970s the Forest Service becomes receptive to the idea of using prescribed burning, which involves the use of fire under closely monitored conditions, to short circuit this build up of fuel, but there is a great deal of emotional baggage which goes with this shift in policy. After several decades of resisting the idea of using fire in the chaparral, the Forest Service must now convince the public that not every fire is bad. In an agency that has given us Smokey the Bear and the slogan “Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires,” this is not an easy sell.

Smokey is a product of the 1940s. During the previous decade the emphasis has been on labor intensive means of suppressing wildfires. Road construction, firecamps, fuelbreaks, fuel modification, and other menas of providing access to the back country rely heavily on CCC manpower.

By the end of the 1930s, as the labor pool begins to dry up, officials begin to focus on fire prevention and the use of the mass media to popularize it. In 1937, artist James Montgomery, creator of the Uncle Sam poster (and the slogan “I want you”), is hired to create a series of posters with patriotic overtones. The fire officials hope to equate forest protection in the public’s mind with the nation’s defense.

In 1944, the Wartime Council licenses use of Bambi as a symbol for a second series of posters. But when licensing problems develop, the council decides to conceive its own symbol. In 1945, the first Smokey the Bear poster appears. Named after New York city fireman “Smokey” Joe Martin, it is drawn by Albert Staehle.

The slogan, “Remember, only you can prevent forest fires” is added to the poster in 1947, and in 1950, in a stroke of pure genius, a live bear is used in the advertising campaign. When an orphan cub is discovered after a large wildfire in the Lincoln National Forest in New Mexico, firefighters there adopt “Little Smokey,” and shortly afterward it is flown to a permanent home at the Washington National Zoo, where the cub is used to film a number of television commercials based on the theme developed in the poster campaign.

The symbol becomes so popular that, by 1952, Congress is forced to pass the “Smokey Bear Act” to regulate commercial exploitation of it. After 40 years, Smokey is still as popular as ever.

While the Chumash and first Spaniards cause a significant alteration of the natural landscape, the change potentially the most difficult to deal with does not occur until much later, in the 1960s, when the South Coast population begins to expand dramatically. In 1960, the Goleta Valley is home to 19,000 people; a decade later 75,000 people live there. Tract housing absorbs much of this boom, but the expanding population also begins to expand up into the fire-prone canyons and hillsides.

Hundreds of large, sprawling ranch-style homes covered with wood shingles, custom designed around clusters of oak and other heavy vegetation, invade the flanks of the mountain wall. The roads are narrow and winding, privacy guaranteed by lush gardens, graceful eucalyptus, and rich, green forests of pine. The views from these beautiful homes are spectacular.

By 1964, when the Coyote Fire occurs, wildfires no longer burn just the chaparral. Now they consume houses, and people too.

*************************************

THE TYPICAL fire begins on a sunny afternoon in August or September. It has been hot for several days in a row and by mid-afternoon the santana winds pick up, blowing downcanyon and across the dry grassy foothills. A car parks nearby, its muffler straddling the grasses. There is a wisp of smoke, then suddenly a burst of flame. The grass catches quickly, the wind fanning the flames. By the time it is spotted several minutes later, the scorched area has grown to 50×50 feet in size.

The smoke, visible from County Fire Headquarters, gets them into action. A pumper is dispatched immediately. Meanwhile the Forest Service, monitoring the radio frequency, begins to roll, and at Goleta Airport the B-25, which is there on standby, is in the air within 10 minutes of the fire’s ignition.

A base of operations is set up in a schoolyard near one edge of the fire. Depending on where it occurs, and in whose zone of responsibility it is in, one of the City, County, or Forest Service officers is appointed fire boss. In the more up to date terminology he or she is known as the Incident Commander, or IC to the fire personnel. The plan of attack is developed within minutes by the operations officers assigned to the IC and the logistics officer makes a call to the Southern California fire operations office in Riverside requesting mutual aid.

Though the response is incredibly quick, the fire’s edge reaches a grove of oaks and the fire crowns, the trees crackling with intensity. The wind takes the burning embers, which are falling everywhere, and hurls them back up in the air, scattering them ahead of the fire line and across the road, expanding the fire dramatically.

Within an hour, racing from ridgeline to ridgeline, it has burned to the edge of a score of homes just above the foothill road. Firefighting forces are now faced with a difficult decision, to save the structures at the cost of losing the fire line or to abandon the houses to the whim of the wind.

The roads are choked with people, making access to the fire very difficult for the firemen. Some of the people are spectators; most of them are hurrying to their homes, either to try a last ditch effort to save them, or to get one carload of valuables out before everything else is consumed. Almost every roof has someone on it, hoses watering them desperately. The water pressure drops and this, too, inhibits the fire control effort.

Everything is chaotic. Some lead frightened horses from the smoke and fire; others cry frantically, shouting out the names of favorite pets, hoping they have survived the holocaust. Police barricades are hastily set up, and people scream at the officers, who will not let them pass through.

When the wind shifts, the neighborhood looks like a war zone, bombed-out houses black with soot and the grime of ash. Some have been burned to the ground, others are only partially destroyed. There is no visible pattern as to why some went while others are spared. The next morning people awake to hills of black and plumes of smoke rising from hundreds of hot spots which still smolder. Everything looks dead.

That afternoon the pattern is repeated again, the fire creeping back down the hillside to threaten new homes, only this time a thousand men and women are there to fight it. Overnight forces have been mobilized from throughout Southern California. They work hard to establish a perimeter around the fire.

Hot shot crews cut small hand lines around the most inaccessible parts of the fire’s perimeter. Helitankers are busy making water drops on the fire’s edge. Men and pumpers line highways and smaller roads. High above, a solitary plane mounted with what is called a probe eye takes infrared pictures which are developed, printed, and in the hands of the fire boss within a half-hour. The aerial tankers are guided by smaller planes onto the hottest of the hot spots which have been spotted on the infrared film, disgorging thousands and thousands of gallons of red fire retardant.

Small victories are gained when the wind dies down; there are heavy losses when it surges. In the command center updated weather reports are received every half hour. There are prayers for a shift in weather.

The next day they are lucky. The wind lays down and cool marine air begins to flow into the fire zone. Within a day the line around it is secure and containment is announced.

Stories appear in the paper in the following days, detailing not only of the fire’s progress, but those about people-the heartbreaking losses, the courage, the terror, of the thousands of volunteers who stepped forward to soften the blow.

The losses are totalled. The firefighters go on to the next fire. People wonder what they will do when the next fire on the hills breaks out.

On the hillside not everything is dead. A few weeks afterward a picture appears in the same paper of an ashen hillside, long black fingers of fire-burnt manzanita all that stick out of the ground. At the base of one a small apple-green shoot has emerged from the burl, a spark of life, an affirmation of the chaparral’s response to fire.

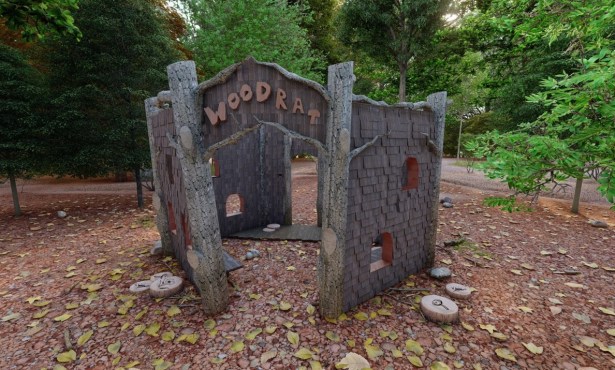

The ground is covered with what looks like a volcanic ash, six inches thick, powdery, seemingly a place where no other life will exist again. But looking more carefully the tracks of the small creatures are there, the ones who have burrowed. While on the surface the temperature has reached 2,000 degrees, the fire has passed over their subterranean homes quickly and many of the snakes, spiders, ants, rats, and other creatures have survived, as have many of the more mobile animals such as deer, bear, coyote, raccoon, and bobcat, though these will not return until the vegetation does.

By November, when the first rain comes, a thick cluster of greenery surrounds the base of the manzanita and the hill is dotted with many more of them. Though they are as dense as teakwood, the burls store nutrients, a supply of water, and buds that are dormant until heated sufficiently.

In December the seeds begin to sprout. Some of them have lain buried in the layers of leaves and decomposing material for 20 or more years. They are called fire followers, or ephemerals, a group of grasses, herbs, and colorful wildflowers which have a coated seed that must be burned off in order to germinate. It is these plants which the Chumash have harvested after a fire.

Some of them are golden poppies; others lupine, chia, tidy tips, gold fields, and cream cups. By spring lilies and other bulbous plants begin to send up shoots, covering the hill with a carpet of loveliness unimaginable in the aftermath of the fire.

Though they last only a few years, the fire followers are rich in nutrients. First they supply food for burrowing rodents, small rats and mice; as they reach 2-3 feet in height birds begin to migrate back into the area, as well as the predators which feed on the smaller creatures. By May the deer return, browsing on the sweet-tasting food.

After about seven years, the chaparral has filled in the gaps between the individual plants, and as they do, they drop leaves which contain chemicals poisonous to those outside their own species, causing many of the fire followers to die back. As the canopy closes overhead, it also chokes off the light, further limiting the ability of the herbaceous plants to grow.

At age 10 the chaparral approaches maturity. New shrubs still appear from seeds that are dropped on the ground, though now they find it difficult to compete either with their parent plants or others for space, light, and water. The chaparral now forms a dense layer of vegetative cover, its canopy continuous, and has become a closed community.

Some of the smaller plants die, unable to endure the harsh summers with insufficient supplies of water. Those which survive begin to reach over each other in search of sunlight. Lower branches, deprived of sun and no longer capable of photosynthesis, shrivel and die, the plants conserving water and energy for those branches at the top which are still useful.

By age 25 most of the chaparral plants are composed of dead, woody material. While they are 15 feet tall, life exists only at the outer edges of the chaparral. The environment below is relatively sterile, the fuel load accumulating year by year, the plants no longer capable of much vegetative growth.

They are ready to burn again.