New Phaidon Publication Illuminates the Work of Edward Hopper

Theater of Light

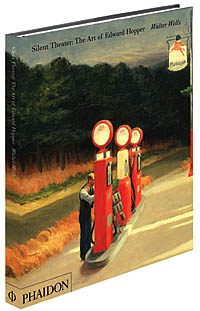

Silent Theater: The Art of Edward Hopper by Walter Wells, recently published by Phaidon, is a comprehensive survey of the artist’s work that coincides with the major retrospective now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. What is it about Hopper, the celebrated 20th-century American painter, that continues to capture the fascination of the American public? Formally, Hopper’s realist paintings are starkly cinematic, with strategic contrasts of warm and cool hues and intense juxtapositions of light and shadow. His style verges on the primitive, and yet his scenes are compelling, evocative, and haunting. There is a sense of psychological detachment and distance between his subjects, who appear frozen in time, often amidst dramatic symbolist landscapes that encroach upon the urban spaces his figures silently inhabit.

My favorite Hopper painting is “Soir Bleu” (1914), which I always return to and spend much time looking at whenever I visit the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. This early image, reproduced in Silent Theater, reveals an intimate restaurant balcony with three tables, colorful Chinese lanterns floating above it, and a high, uneven horizon where deep blue sea meets violet air. At the central table sits a bald-headed clown, all in white save the red makeup on his eyes and lips, accompanied by two men in dark clothing; a woman in an olive green dress stands behind them. A couple in smart evening wear sits at the table to the right, while a lone figure occupies the table to the left. The scene is mysterious, uncanny, and strangely mesmerizing-the enduring qualities of Hopper’s work.

At first glance, Silent Theater appears to be another beautiful coffee table accoutrement-something to flip through for the gorgeous images-but the allure of Hopper’s work soon draws the reader deeper to explore 15 thematic chapters. The author examines in depth the sense of memento mori, or mortality, and the Oedipal imperative that he suggests appears throughout Hopper’s oeuvre. Wells employs a multilayered approach, incorporating biography, psychology, social and historical context, and iconographic and even semiotic readings.

Hopper (1882-1967) studied at the New York School of Art with noted landscape painters William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri. After seven years he left for Paris and traveled in Western Europe during a pivotal moment in the modernist period. Unlike his European modernist contemporaries, who were experimenting with surrealism and then abstraction, Hopper painted restrained realist images that reveal a philosophical American pragmatism. His compositions are often utterly American, especially his use of New England architectural details and his Cape Cod scenes depicting lighthouses and sailboats.

As Wells points out, Hopper studied at an art colony in Ogunquit on the coast of Maine in 1914 when WWI began in Europe and continued to spend lengthy summers in New England throughout his life. Among his images of rural America is “Gas” (1940), painted during the beginning of WWII. The work depicts a new gas station with an attendant at the first pump. The eerie scene is lit by multiple sources: the twilight of the darkening night sky, the artificial light inside the station, and those illuminating the pumps and signpost. The gleaming red-and-white pumps and incandescent lights are symbols of modernity, though they are surrounded by traditional architecture and rural landscape. The Mobilgas sign, with its image of a flying Pegasus, and the open highway beyond, seem to suggest freedom and the power of mobility, yet that freedom is hinged on uncertainty: The open road recedes into a dense, unlit forest.

The use of artificial light as almost a subject in its own right recurs often in Hopper’s work, notably in the iconic “Nighthawks” (1942). In this dramatic night scene, the intense yellow light of a diner is juxtaposed against the dark greens and bluish grays of the architecture itself and the deep shadows of the street outside. The bright glow reveals three patrons sitting at a bar and a server facing them. Though the four subjects share a limited space, they appear detached from one another. The server peers out of the window toward the building across the street, while the couple across from him sits stiffly; the woman in the peach dress examines the slice of lemon for her tea, while her escort holds a cigarette and looks furtively towards the server. The fourth figure sits hunched with his back toward the viewer. The desolate street outside occupies a third of the composition, heightening the sense of loneliness.

Wells asserts that the concept of voyeurism, often applied to this and many of Hopper’s works, should be used in moderation and considered more as a visual vantage point than as a synonym for eroticism. In this case, the viewpoint suggests an onlooker peering inside the diner from across the street, interested but unable to participate. Hopper was typically an outsider in most social situations, and would likely, Wells suggests, have been diagnosed today as depressive. It is likely that Hopper projected his own sense of melancholy and voyeuristic tendencies onto his canvases, for these are pervasive and alluring themes in his work.

The viewer of Hopper’s paintings, then, is given the privilege of supplanting the artist, taking on the strange perspective of one who simultaneously engages and avoids, as do Hopper’s subjects themselves. The figures in his paintings ultimately remain isolated from one another, even when portrayed in moments of intimacy, as in “Summer in the City” (1949) and “Excursion into Philosophy” (1959). The former shows a woman sitting pensively on the edge of a bed while her male lover lies nude behind her, facedown in the pillow. The woman’s feet rest squarely in the reflected light of the window, and she herself is lit by this same light source. The latter image reveals the naked posterior of a woman who appears asleep while her male partner is fully clothed. An open book rests by his side, while he sits gazing into space as if deep in thought, the tips of his shoes illuminated by the light streaming in from the open window to his left.

Wells asserts that light is an essential element of Hopper’s work, one that is used for a multitude of aesthetic and emotive purposes, but whose ultimate power lies in is its ability to reveal the subject. Further, Wells suggests, the light represents Hopper himself-the director who operates the stage or theatrum mundi-and, paradoxically, once we recognize this, the uncanny quality of the paintings diminishes somewhat. Or does it? However contrived and artificial their staging, Hopper’s images continue to capture the imagination, remaining mysterious, captivating, and just beyond the reach of reason. Therein lies their power.

Wells’s engaging insights into the artist’s life and artistic vision, presented alongside 170 beautiful color reproductions of Hopper’s work and the addition of etchings from the artist’s rarely seen sketchbooks, make this publication essential study for any fan of Hopper, as well as for anyone interested in seeing new light shed on familiar-if enigmatic-subjects.

4•1•1

Walter Wells’s Silent Theater: The Art of Edward Hopper, is published by Phaidon Press and is available at phaidon.com, amazon.com, and in select bookstores. For more information, visit phaidon.com.