Big Waves, Beat Downs, and the Birth of Modern Surfing

A Revolution Revisited

In 1975, there was no such thing as a world champion in the sport of surfing. There was no professional tour, no big money contests with international sponsors, no chain stores in middle America selling surf clothes to pale-skinned teenagers who have never seen the ocean. Surf companies didn’t enjoy success on the New York Stock Exchange and men and women certainly didn’t earn millions of dollars a year to chase perfect waves around the world. There were only waves, boards, and riders, the occasional contest with peanut prizes, a budding surf-minded media, and a testosterone-driven swirl of reputation, rumor, and ambition hanging over those who chose a surfer’s path.

From the rose-hued vantage point of hindsight, the mid 1970s were a golden era of sorts for surfing; it was a time when crowds were still mellow, pursuits still pure, and anyone willing to buy a plane ticket to Hawai’i, paddle out, and make a death-defying drop could earn a name for themselves the world over. It was from the soil of this fertile time-thanks to the unblinking bravado and athletic prowess of a rag-tag bunch of young, shaggy-haired board riders from South Africa and Australia-that the sport of surfing as we now know it was born. As current Montecito resident and former World Champion Shaun Tomson recalled recently of those heady years, “It’s not like we had some specific objective to change surfing. We just wanted to be the best and be the most radical; and I guess somewhere in that process, modern surfing was born.”

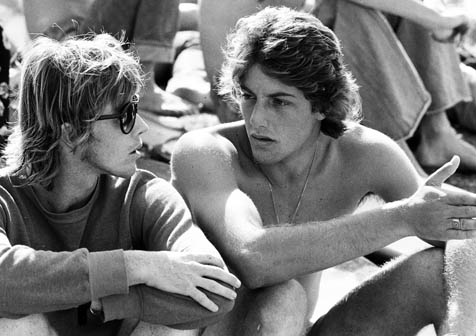

Mark Richards, Wayne “Rabbit” Bartholomew, Shaun Tomson, Michael Tomson (Shaun’s cousin), Ian Cairns, and Peter Townend. The names are certifiable legends in the annals of professional surfing, for without them and their groundbreaking performances in the waters along the North Shore of Oahu, Hawai’i, during the mid 1970s, the current surfing culture would not exist. They traveled around the world as teenagers-living in relative squalor, risking life and limb taking on the most challenging waves in the world, and locking horns with an established and equally legendary guard of Hawaiian surfers-with the hope of earning themselves a reputation and perhaps enough money to do it all again the following season. It was a labor of love driven by desire and the type of youthful exuberance that young men often find burning in their bellies as they come into their early twenties.

Unlike today, when aspiring surfers can enter contests at their local beaches and climb a well-worn, familiar ladder to success, contest entrances in the mid ’70s were a rare privilege given only to those who had a known reputation as a hot surfer; the only way to earn that status was to go to Hawai’i and drop into the biggest, baddest waves you could find no matter who or what stood in your way. Famously described in a 1976 Surfer magazine article by Rabbit titled “Busting Down the Door,” the situation was such: “The fact is that when you are a young emerging rookie from Australia or Africa, you not only have to come through the backdoor to get invitations to the Pro meets but you have to bust the door down before they hear you knocking.” And when these young men did just that-feeding off each other, tube riding, carving, and hitting the lip on big Hawaiian waves in a way never seen before-not only did they set off a media storm, which produced iconic photos and groundbreaking surf films that forever altered the direction of surfing, but a few of them also nearly lost their lives in the process.

Golden Years and Dark Days

“Those were some of the best years of my life,” said Australia’s Mark Richards, a four-time world champion, in a phone interview from his surf shop in Newcastle, Australia. “I didn’t have a care in the world except driving a 200-buck rent-a-bomb to the beach and getting tubed off my dial at Off-the-Wall [a surf break just down the beach from the world-famous Banzai Pipeline] with my mates all day in absolutely perfect surf. It really was like living in a dream.”

Richards and fellow Australians Rabbit, Cairns, and Townend had traveled to the North Shore for two seasons prior to the fabled 1975 winter but had rarely cracked the contest scene, let alone made a name for themselves. Similarly, a South African contingent, lead by Tomson and his cousin Michael, had done time on the island prior to that fateful year, but the results had been far from what they had hoped for. It wasn’t until ’75-’76, with the experiences of a few seasons under their belts, that the crew really began to stand out. “We hit the North Shore that year with the attitude of ‘let’s not just flow, let’s attack.’ We wanted to translate our small-wave surfing to the open canvas of a big wave and rip the shit out of it,” recalled Richards. And that’s exactly what they did. The crew went from barely getting into any contests in 1974 to taking home first, second, and third in every major contest on the North Shore in 1975. Even more importantly, during downtime between competitions, they free surfed with each other, pushing their boundaries and driving one another to improve. “No one wanted to be the lagger or the weak link,” said Richards. Tomson put it more directly: “I’d be pissed if Rabbit or Mark got an insane tube and I’d just be sick to myself until I got a better one. It was good-natured but also pretty intense between us.”

Their high-performance slash-and-burn approach to surfing-which really looked other-worldly compared to the established casual stylings of Hawaiians like Jeff Hakman, Michael Ho, Peter Cole, and Gerry Lopez-and competition-charged camaraderie was immortalized by Brooks Institute dropout Bill Delaney in his seminal film Free Ride (released in 1977). When the smoke cleared on the North Shore’s ’75 season, both Surfing and Surfer magazine were stuffed with pictures (most of them taken by Santa Barbara’s Dan Merkel) of the new crew doing their thing, and the surfing world was set ablaze. “I don’t think any of us could have done it single-handedly but collectively we changed surfing. It was a really special group of guys in a really special time,” explained Rabbit.

Seldom is there accomplishment without ego nor is there change without friction, and as the surf media became more endeared with the South African and Aussie crews, the Hawaiians began to take exception. Already pissed off about the attention shifting from them to the young guns, the Hawaiians were further antagonized leading up to the 1976 season by the aforementioned Surfer magazine article by Rabbit as well as another similarly themed chest-thumping piece by Ian Cairns. The Hawaiians had been beaten in contests, insulted in the press, and felt their culture had been mocked by the white South African and Aussie upstarts. So when winter ’76 rolled around, they were prepared to do something about it. Rabbit arrived first to the islands and was promptly beaten to a pulp in the water at Sunset Beach; death threats and alleged contracts for the murders of Rabbit and Cairns were drawn up, not to mention frequent beat downs for many others in their crew. Though they all shy away from talking about specifics, Richards recalled “a fair bit of violence and intimidation,” while Tomson summed it up by saying, “I don’t think anyone really has any idea about the things we went through just to surf that year.” After hiding out, sometimes in bushes, for days on end or holing up in a hotel room with shotguns and baseball bats, peace was brokered and the Free Ride generation-as they have come to be known-continued their march toward destiny, though this time with a decidedly more humble approach.

A Chance to Remember

Thanks in large part to the efforts of Rabbit, Tomson, Richards, Cairns, and Townend, the International Professional Surfing tour was born in 1976 and took full flight in 1977, paving the way for the World Championship Tour of today, which travels to the best waves on the planet and offers winners’ checks for tens of thousands of dollars while helping inform a multimillion-dollar international industry.

Despite the fact that the five men have, and continue to, play formative roles in the development of professional surfing, their coming-of-age story has been largely overlooked by today’s younger surfers-until now. Created primarily as a labor of love with no industry funding, Tomson has teamed up with 34-year-old filmmaker Jeremy Gosch to make Bustin’ Down the Door, a documentary film that brings to the big screen the triumphs and tribulations of the revolution of 1975. Combining awe-inspiring and often iconic surf footage from more than 17 surf films, such as Free Ride and Standing Room Only, with insightful and emotional interviews from the key players-be they Hawaiian, South African, or Australian-the film aims to do for the birth of modern surfing what the 2001 documentary film Dogtown and Z-Boys did for the origins of skateboarding several years ago.

A self-described “Val[ley] kid making a surf film,” Gosch explained his motivation recently. “I’ve always felt that no one in Hollywood has ever really done surfing justice besides Big Wednesday and Apocalypse Now. It has always been a goal of mine to tell the real story, and hopefully with this film we’ve done just that.” With Ed Norton narrating, the full cooperation of all parties involved, a soundtrack that includes The Doors, the Rolling Stones, and Pearl Jam, not to mention high-definition water footage that remains relevant, jaw-dropping, and cutting-edge some 30 years after it was filmed, the movie goes a long way toward achieving Gosch’s goals.

Furthermore, the movie peels back the outer layer of simple surfing achievement and reveals a deeper, more valuable story of pioneering young men who risked everything to achieve something that didn’t even exist yet. “This film isn’t just about surfing,” said Tomson recently over coffee in Montecito. “It’s about making your dreams come true. It takes people to a place that is so unexpected.” He then paused and added without a trace of braggadocio, “It really is the most unique surf movie ever made.”

4•1•1

Bustin’ Down the Door has its world premiere on Sunday, January 27, at the Arlington Theatre as part of the Santa Barbara International Film Festival. Visit bustindownthedoor.com for more information.