On the Road – Santa Fe Trail

State Highway 400 to follow the Arkansas River valley east through Kansas

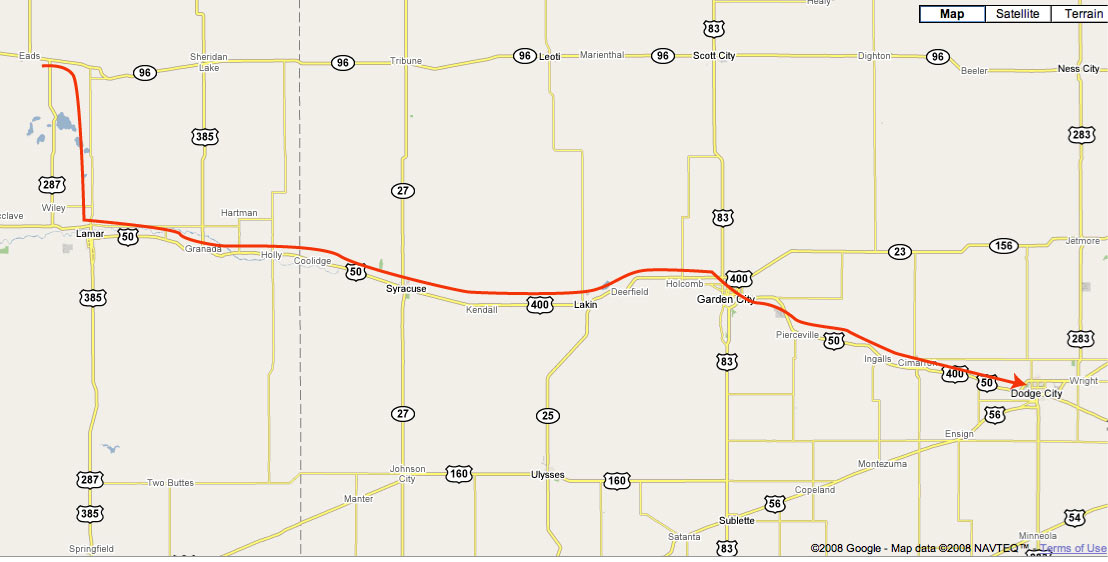

After breakfast in Eads and my side trip to the Sand Creek Massacre historical site, I drop down to State Highway 400 to follow the Arkansas River valley east through Kansas. For most of the rest of the trip across America I’ll be on local highways and back country roads, weaving my way through Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Kentucky and the Virginia states to Washington DC.

The weather is warming as I continue east through the last bit of Colorado. Nearing lunch time I pass through the small town of Holly, birth home of former governor Roy Romer and I’m in Kansas. I can almost see a glimmer of sunshine on the horizon. I’m now firmly in farming country. The hillsides are green and though the crops have not yet been planted, the soil is being tilled by huge industrial sized tractors, fully enclosed with glass and with their heaters blasting, I’m sure.

Now and then I catch a glimpse of the Arkansas. I had imagined the river to be much larger, with deep banks to plentiful stands of tree lining them to mark its place in history but I’m disappointed. The land is just too flat and the river course more a depression in an otherwise uniformly horizontal plane. Nevertheless, it was substantial enough in the 1820s to sustain those who were searching out a southern route down into what is now New Mexico.

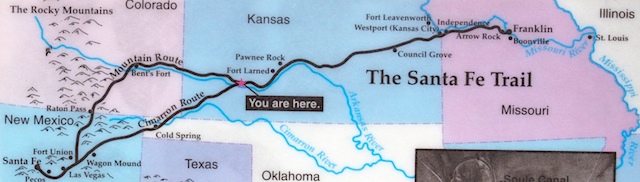

In 1821, when William Becknell left Franklin, Missouri on his first trip the western US with a load of freight to deliver to Santa Fe, New Mexico he was about to open a new chapter on the western frontier – establishment of the routes west of the Mississippi that would support the greatest migration in in American history. Mexican independence had opened up trade routes in areas of the Southwest forbidden by the Spanish prior to this.

On the first trip, Becknell followed an obscure Osage Indian trail through southern Kansas and Colorado to Santa Fe, Becknell bringing his merchandise in by pack mule and horses. The trip was successful enough that the following year he returned bearing wagons full of trade goods. He found the wagon route passable despite the 800-mile route, 230 of which along the Arkansas River stretching from Fort Larned and Fort Lyon in Colorado.

Within three years the route was so popular the U.S. government had negotiated a treaty with the Osage Indians and by 1827 surveys had been completed that established the Santa Fe Trail as the first “public highway” in the American southwest. In the 1830s this would be followed by the development of the Oregon Trail. Together they would make it possible for more than a half million people to head west over the next forty years.

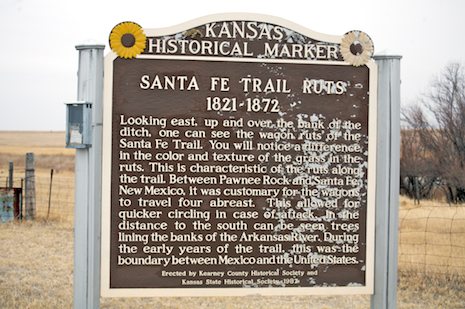

At one point I spot a turnout that advertises the opportunity to see the ruts made by the original Conestoga wagons as they made their way along the Santa Fe Trail. They aren’t much, just faint depressions that would go unnoticed if it weren’t for the signs marking them. Still I find the scene impressive. The American frontier – ranging in earlier periods through the Appalachia Mountains through Kentucky and Tennessee to Saint Louis and then beyond along the Santa Fe and Oregon trails – is intimately tied to the development of the American character. Hardy, tough, self-reliant – all characteristics of the American spirit that has formed the backbone of who we are.

I can almost imagine the sound of the wagon trains, four abreast, the pounding of the horse’s feet, the creaking of the huge wooden wheels, the shouts of the wagon masters urging the stock on. Or perhaps it’s just the sound of the cars and trucks behind me, cruising along so effortlessly on Highway 400.

For me the journey across this part of the Plains will take less than four hours. For those hardy pioneers, the 800 mile trip from Independence, Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico might take as much as eight weeks. The journeys were unpredictable at best – intense spring and summer storms, flooded rivers, buffalo stampedes, intense heat – and of course the ever present danger of Indian attack. Tough life.

But like my parents in the 1950s, the promise of a better life lured them west. No matter the hardships: some came for the easy buck, their eyes glazed over by gold fever, but most came looking for land to settle, a place to live, the promise of something better than they had before.

There were those, too, who believed that it was our destiny to settle the west. In 1845 journalist John O’Sullivan expressed the sentiments of many when he declared that it was “our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” Regardless of the motivation, the westward movement was on.

I’m on to Dodge City – home of Matt Dillon, mythical sheriff and justice of the peace – who I grew up with in my early teens. A rough cowboy town a hundred years or so ago, its prosperity was first tied to the massive cattle drives that would be taken each year to Kansas City where the railroads were located. The town appears to be peaceful enough now as I drive through. I’m impressed by the fact that all of the city’s streets are paved with brick, set diagonally in a pattern that provides a beautiful juxtaposition to the charming wood and brick homes that line them.

Finally, the sun has come out and I can get out and stretch without the fear of being assaulted by the bone chilling winds I’ve experienced the last two days. Just a few miles ahead of me is the town of Ford, Kansas. The town was named after someone else with the same last name of course, but it’s kind of neat, nevertheless to see the sign welcoming me. Beyond are a handful of other small towns – Mullinsville, Greensburg, Cullison – that don’t mean much to me now but which will leave a lasting impression once I’ve passed them by.