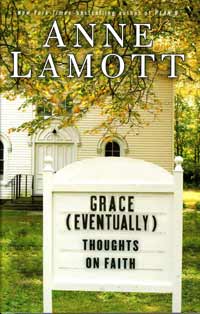

Grace (Eventually) Author Anne Lamott Finds the Holiness in Being Human

Faith in Imperfection

Most of us can name a moment when we realized that perfection was just a fantasy, that the seemingly superhuman being we admired, emulated, even deified, was only human after all. One of my earliest memories of such an awakening involved Mrs. Kircos, my first-grade teacher. Mrs. Kircos seemed to have a never-ending collection of wonderful storybooks. When she read them to us she would let us gather on the floor to listen, and I would be transported, as if the nondescript rug at her feet were a magic carpet. Mrs. Kircos gave us a reading challenge: If you read 20 books by the end of the year, you were invited to a pool party at her house. I imagined a castle with a moat, a palace with formal gardens where I would romp through fields of clover and nap in the shade of ancient trees. I read and read, determined to be chosen. Finally, the day of the pool party arrived, and as I stepped through the front door I experienced something like a paradigm shift: Mrs. Kircos had a suburban house where she did earthly things like eat toast and do laundry. As I stood in her living room holding my threadbare towel, I realized that Mrs. Kircos was human, and what she was sharing with us was, strangely, even better than fantasy-it was her real life.

More than any author I know, Anne Lamott captures just that: the sanctity of our sometimes messy, often flawed, and undeniably real humanity.

Lamott is perhaps best known as the author of Bird by Bird, a compendium of writerly advice taken from every teacher she’d ever had and directed at any would-be author looking for guidance. The title comes from one particular childhood memory: her 10-year-old brother hunched over the kitchen table despairing about a report on birds he had put off until the day before it was due, his father speaking gently to him. “Bird by bird, buddy,” Lamott recounts her father saying. “Just take it bird by bird.” Among the book’s many nuggets of wisdom is the concept of “shitty first drafts,” a piece that forever changed the way I view my own sloppy writing process and earned Lamott a place in my pantheon.

Lamott’s latest book is Grace (Eventually): Thoughts on Faith, a series of short essays in which she explores the human conditions that have always been at the center of her work-desire, loneliness, anger, forgiveness, love, gratitude; in a word, spirituality. Faith is not a new theme for Lamott; her earlier collections, Traveling Mercies and Plan B, both took the same topic as their basis. But in these essays, the author known for wickedly funny writing about her history of alcoholism and substance abuse, the adventures of single motherhood, and becoming a born-again Christian seems tenderer than ever before.

“What aging has taught me,” she told me over the phone from her San Francisco Bay Area home, “is the grace of surrender and letting go. I think the biggest gift of aging is that there used to be all this stuff you cared so much about that you couldn’t care less about when you’re older. Your values become clearer. By the time you’re 50, some of your friends have died, and it helps you experience the preciousness of life and the wild unpredictability of it all. But the most important thing has been that with every decade I have gotten so much freer from the toxic self-consciousness of my youth.”

That’s not to say she’s freed herself from the self-awareness required for astute and disarmingly personal writing-Lamott’s ability to capture in simple language the messy, tragic, joyful, agonizing experience of being human is what makes her work so riotous, and so appealing.

Among the stories in Grace (Eventually) is “Nudges,” in which Lamott describes her own childish behavior, driven by jealousy at her friends’ affluence, and her eventual attempt at reconciliation. I asked her whether she finds readers treat her as a kind of spiritual guidance counselor, and whether she thinks she’s qualified for the job. “I’m a completely unavailable person, except for my work,” she told me, “so I tend to try to share stories and experiences that I know are universal. A lot of people who come to events are people who left the churches of their childhoods and have been looking for a spiritual community where they won’t be shamed, chastised, or judged. I certainly don’t do those things. Mostly, I pass along what I believe to be true.”

For Lamott, human foibles are worthy of celebration as well as ridicule, and her accounts of her own imperfections only endear her to readers who recognize themselves-and humanity as a whole-in hilarious descriptions that are moving precisely because they are true. “I’ve written that laughter is carbonated holiness,” she told me. “I love to make people laugh. I love that people find my writing is useful in terms of saying what the spiritual life is like-that it’s not about tidiness and order. It’s like fits and starts.”

Faith and spirituality, it seems, just like writing, require constant revision. Lamott knows all about that. “My first drafts are really bad, and my second drafts aren’t all that much better,” she said, “but when the first draft is done, I feel a huge amount of relief that it’s out and it looks as if I might just be able to pull it off again. I have to remind myself that it’s all process; it’s incremental and messy, but you just keep having faith that if you’re trying to do it as well as you can, then something will arise from that.”

Amen.

4•1•1

Anne Lamott will read her work on Sunday, April 6, at 4 p.m. at UCSB’s Campbell Hall. For tickets or more information, call 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.ucsb.edu.