Why the Biggest Acts Love to Play in Our Backyard

The Bowl Alternative

There’s one near virtually every American city-an outdoor amphitheater designed to hold thousands of people and host touring rock shows during the summer. From the Alltel Pavilion in Walnut Creek (that’s in North Carolina) to the Waikiki Shell, these giant facilities, with their oversized parking lots and “great lawns,” usually promise the moon, but can’t always deliver the stars. For every sold-out jam band show at Colorado’s famous Red Rocks, there are a dozen anonymous pavilions where road-weary oldies acts headline for half-full houses.

Not here, though. The Santa Barbara Bowl, which is entering its 72nd season, only holds a relatively modest 4,562 seats. But tucked away at 1122 Milpas Street, on the top of a busy city street and 15 blocks from the nearest freeway, our Bowl, nestled among Riviera family homes and Eastside Craftsman cottages, routinely delivers the most sought-after entertainers in the world. Far removed from the suburban sprawl of ordinary outdoor concert venues, the stars come out to play. In recent seasons, audiences at the Bowl have thrilled to concerts by the biggest names in popular music, including Stevie Wonder, Paul Simon, Rod Stewart, Gwen Stefani, Pearl Jam, the Eagles, and Radiohead. Any of these acts could easily fill their touring schedules exclusively with larger venues, but thanks to a dedicated and experienced team of people working 52 weeks a year to create the peculiar magic that is the Santa Barbara Bowl experience, we get to see acts up close and personal who would otherwise only play the major urban markets and the big festivals.

The Moon Is Free

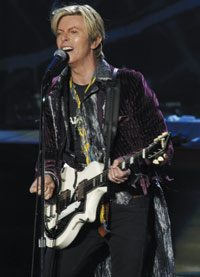

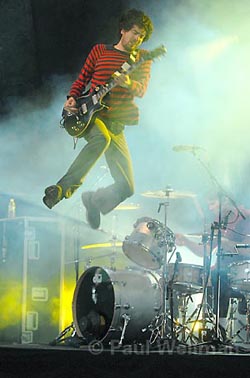

Outdoor shows like the ones that start this weekend, when ’80s titans Duran Duran open the Bowl season on Saturday night, answer a kind of primitive need. When summer comes, and the late afternoon sun lasts for hours, the act of gathering in large groups outdoors takes on special meaning. For the ancient Greeks, amphitheaters like the Bowl served both acoustic and spiritual purposes, amplifying the sound of the human voice while promising potential communion with Dionysius, the god of intoxication and revelry.

As a visit to any of this season’s Bowl concerts will reveal, the spirit of Bacchus is alive and kicking. When the sun goes down and the moon comes up, you can be sure the concession area will be busy and the crowd will be dancing. Whether it is to blissful standards with Tony Bennett, or the crunching rock anthems of 311, people come out to the Bowl to get their summertime groove on, and the performers notice the vibe.

Disco diva supreme Donna Summer remembers the first time she saw a show at the Bowl: “It was in the late 1980s, and my husband and I drove up from Los Angeles to see Sting. The music was great, and just when I thought it couldn’t possibly get any better, sitting there listening to this great band and looking at the ocean, out came a beautiful full moon, and I thought, ‘How much extra does that cost?'”

The moon, of course, is free, but nothing else in the high-flying world of big-time concert promotion comes without a price tag. Although the beleaguered music industry has taken heart at the relative strength of concert ticket sales amid otherwise dwindling revenues from traditional markets, the community that organizes and books the major tours remains a small and select group. Agents, tour packagers, and talent buyers all know each other, and together they play a high-stakes game with no limit and few hard-and-fast rules. To succeed in this competitive environment, talent buyers have to know and leverage every available angle.

Bidding on Talent

No one in the music industry today plays the game any better than Moss Jacobs, vice president of talent at Nederlander Concerts, Inc. This Los Angeles-based arm of the venerable, privately held entertainment company has become the gold standard for many top acts when they consider their options for outdoor venues, and Jacobs is an acknowledged expert, one of the few people in the business able to make the kind of multi-city, multi-venue offers that get major artists out on the road. For example, the recently announced Sheryl Crow concert at the Bowl is part of a three-venue deal that Jacobs put together in which Crow and Los Lonely Boys will perform at Red Rocks outside Denver on Monday, June 9, at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles on Wednesday, June 11, and at the Santa Barbara Bowl on Thursday, June 12. As the price of going on a traditional national tour continues to rise, these multi-city mini-tours are fast replacing the financially riskier and infinitely more arduous months-long road shows of the past.

According to Nederlander Concerts CEO Adam Friedman, this kind of imaginative, fully realized multi-venue booking is what sets his company apart: “The multi-city offer allows the artist to capture a string of dates in a single offer, which saves time, creates unique routing, and forges a stronger bond with a promoter who’s dedicated to making sure the entire run is successful since we’re not handing it off. Even if we’re booking multiple venues or cities at once, we’re still focused on the success of every single show. We’re able to do this because we’re not consumed by the national footprint” of booking full tours. In other words, Nederlander is now committed to a corporate strategy that Moss Jacobs has been implementing all along.

An empire and a reputation the size of Jacobs’s is not something that can be put together overnight, and part of the reason he works so well in Santa Barbara is that he got his start here. Raised in Miami, Jacobs attended UCSB and dates his concert promoting career to his undergraduate adventures running street parties in Isla Vista. He was one of the first people to realize the potential market for reggae, a music he says he developed a feeling for when he was a teenager in Florida. His Bob Marley Festivals, done in Los Angeles, San Diego, and Long Beach under the umbrella of “Moss Jacobs Presents,” were the largest reggae concerts in America, drawing as many as 36,000 people during the course of President’s Day weekend. Earlier efforts were even more grassroots. Jacobs remembers the 1980s, when he was just out of college, as a great time for music. “I did a whole bunch of shows at La Casa de la Raza-the Red Hot Chili Peppers, X, and Los Lobos.” His first professional engagement with the Bowl was in the ’80s as well, distributing promotional flyers for a concert by Van Morrison. Soon his talent was recognized, and by 1990 he had joined the Avalon Attractions organization and met up with current Bowl General Manager Sam Scranton. Together they have weathered many changes in management, and continue to persevere in a field littered with the abandoned logos of one-season promotional wonders.

David Books Goliath

But, wait a minute, back to the current season and the recently announced Sheryl Crow tour-isn’t there something wrong with this picture? Red Rocks has 9,450 seats and the Greek Theatre has 5,700. How is it that Santa Barbara, with less than half the capacity of the Colorado venue, merits the Thursday night show at the end of this high-profile run?

That, according to Jacobs, is where the Bowl’s special magic comes into play. When I asked him to describe the way he woos the stars to Santa Barbara, he responded with a characteristic wariness and intensity. “It was a long journey to get it that way. For years in the winter, when it was time to think about touring, nobody in Los Angeles or New York or London-where these decisions typically get made-ever thought about Santa Barbara. The Bowl was not in the kind of shape then that it is today. But now, thanks to the efforts of the Bowl Foundation, I can honestly say that we are taken just as seriously as many venues that are twice the size, and there are four main reasons why that’s the case,” he explained. “First, there’s the physical, technical side of things. With the pavilion and the new backstage, we can load in even the biggest shows and satisfy the pickiest crews because we are now state-of-the-art in the back of the house. Second, there’s the staff. Most large concert venues are fairly anonymous. You load in with a bunch of grim, unsmiling union guys and you see the same old concrete walls until it’s time to go onstage. But here, I have both the Bowl staff and my own people from Nederlander and together they offer a totally different experience. It’s not that it’s not professional; it’s that it is more than professional. From the moment bands arrive, they notice the difference. We just project a very specific vibe, one that is more fun and laid-back. People who tour a lot love to come here because of the community feeling backstage.”

The last two reasons get even more complex, and I listen in wonder as Jacobs warms to the pitch, saying that “the geographical setting, well that’s just unparalleled. Where else are you going to see the ocean from the stage in front of 4,500 cheering, happy fans? No place. Finally, though, it comes down to the fact that we can pull off the financial piece of it. The personal treatment and the down-home atmosphere wouldn’t mean a thing if we didn’t know our business and our market as well as we do. And it’s not just about the big names, the acts that could obviously sell out even at much larger venues. Where we really excel business-wise is with those shows that don’t sell out, yet still reward the acts that come financially. Ultimately, that’s our core strength-that we have the promotional know-how and the marketing focus to make every show work for every artist we book. It’s that reputation for delivering on the business side, combined with the incredible quality of the experience that brings bands, and their managers, back. I just hope that people understand and appreciate how unusual the Bowl is in this; that it is only through a very magical combination of forces coming together during a long period of time that such things are possible here.”

From the Depression to Woodstock Nation

The details of the Santa Barbara Bowl’s fabulous past are truly fascinating. There’s an American epic here waiting to be written, about the changing role of civic pageantry in the California imagination. When Riviera developer George A. Batchelder first proposed that the watery gorge at the corner of Milpas and Anapamu streets might make a good location for an outdoor amphitheater, the Great Depression was at its height, and skilled craftsmen of every description were out of work and hungry for a chance to get involved with one of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal WPA projects. By the time the money came through in 1936, enough skilled Italian stonemasons had gathered in Santa Barbara to erect a latter-day coliseum. Using only the giant sandstone rocks they found on the site, these men built the acoustical and architectural marvel that still stands today. The first shows presented at the Bowl were associated with Fiesta, and involved thousands of community members-many in costume and on horseback-in an outdoor extravaganza celebrating the myth of Santa Barbara’s supposed Spanish origins. These early festivals, like those held in Los Angeles throughout the 1920s and 1930s, were an odd amalgam of civic pride, religious fervor, and naive expressionism. Like the Old Spanish Days Fiesta it was eventually to support, the early Bowl was a fantasy space allied to a vision of the past as it had never been, the Hispanic metaphor of a land apart from the pulling and hauling of commercial America, where gracious ladies and dashing gentlemen could carry on their romantic lives under the stars and in sight of the mighty ocean.

All told, this golden era of the early Bowl lasted less than a decade. It was not just World War II, which shut down the Bowl for the only lost seasons in its entire 72-year history, but also the elements, which wreaked havoc with the ravine, uncovering new boulders every winter and sending them tumbling down through the seating area toward the stage. By 1947, scarcely 10 years after it was opened, the Bowl was already going through the first of many community crises of confidence. Maintenance was more than the city felt it could handle, and many civic leaders indicated that they would be just as glad to see the hillside marvel dismantled and developed to resemble the rest of the Riviera.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, promoters tried everything and anything to get the Bowl to catch on. Early performances of world music were held there, alongside Western-themed Broadway shows like Annie Get Your Gun. In 1962, there was even an attempt at creating a home-grown, Spanish-themed version of Oklahoma!, something called Royal Rancho that promised to do for Santa Barbara what Rodgers and Hammerstein did for Tulsa. But none of this could possibly have prepared the residents of Santa Barbara, and in particular the Riviera neighbors of the Bowl, for what would come next-rock ‘n’ roll.

To many long-time followers of the Santa Barbara concert scene, the late 1960s through the 1970s were the golden era. Steve Cloud, manager of jazz pianist Keith Jarrett and an important player in concert promotion here and worldwide for several decades, says that he sometimes misses the old, run-down Bowl of the 1970s. “The Bowl was a very soulful place when it was in ruins, and as such it was a great antidote to the music industry. The afternoon shows of the ’70s were really special because they were a direct extension of the original festival concept, which was kind of utopian. It couldn’t last that way, and what has been done out there by the [Bowl] Foundation is magnificent, but for those of us who saw it back in the day, that Bowl period will never be forgotten.”

Nor will it be forgotten by the neighbors, who put up one of the fiercest fights in all of Santa Barbara preservationist history, not to have the Bowl preserved and restored, but instead to have it torn down and its site developed. To understand the furor the Bowl concerts of the 1970s caused in the neighborhood, it is important to recover the social and historical context of the period. This was the height of Joan Didion’s White Album California, a place where the hippie movement of the late 1960s had morphed into a decadent, outlaw popular culture that seemed to know no limits either of action or of age. Teenagers with long hair would climb down over the rim of the Bowl through the poison oak and hop the fences to catch shows, bringing their bottles and pipes with them. Community reaction to the Dionysian frenzy was sudden and vehement. A Grand Jury was impaneled to examine the situation, and its report reads today as though it were taken from one of the Hollywood movies of the period, something like Wild in the Streets. In December 1976, the Grand Jury wrote that the Bowl was a haven for “purveyors of discord,” a “young, bottle-throwing mob driven insane by dope, booze, and noise.” Who were these scary kids? The children of Santa Barbarans? Not according to the Grand Jury report, which stated that “hoodlums from L.A.” intended nothing less than to “ravage the countryside and drive Riviera residents into nervous breakdowns.”

When the countercultural dust had cleared, the Grand Jury was ultimately unsuccessful in removing a festive facility that some saw as a public nuisance.

What came next-an external audit of the Bowl’s books-revealed conspicuous gaps in the Bowl’s often sketchy financial accounting. The county had leased the Bowl to Old Spanish Days as a way to underwrite Fiesta. Old Spanish Days’ leader, J.J. Hollister, took an attitude of extreme independence, wondering loudly and often if the county had any right to question his management. The immediate issue in question, as of 1990, was a Bowl “restoration account” held by Old Spanish Days and containing $96,000, the revenue from a 50-cent ticket surcharge that had been in force for several years. Accounting firm MacFarlane, Spengler, and Lynn discovered that, despite having made millions of dollars in gross profits since the mid 1970s, Old Spanish Days had not tracked the Bowl’s revenues with conventional financial scrutiny. In fact, for the period 1978-1982, there were no accounting records of any kind.

The stage was set for the Battle of the Bowl. County Supervisor Gloria Ochoa squared off against Old Spanish Days president Hollister, and they began a duel for control of the Bowl that would continue for four long years of seemingly endless wrangling and hand-wringing. Only at the last minute, with the Old Spanish Days lease about to expire, did the Santa Barbara Bowl Foundation, the nonprofit that is responsible for the massive renovations and improvements of the last 15 years, come to the rescue.

Former county arts commissioner Patrick Davis remembers the era well, and so do Bowl Foundation Boardmembers Paul Dore and Scott Brittingham. Patty Clarke, a tireless advocate for the foundation, was there as well, and took a substantial role in the capital campaign that followed.

During the 14-year period since the foundation obtained its 45-year lease on the Bowl, the community has rallied to support the organization and the facility in a way that is nothing less than spectacular. In August 2000, you could have purchased the right to name the Bowl after yourself for 10 years for a measly $4 million, but Santa Barbara donors mostly don’t roll that way. Dore is struck not only by how many people are willing to make very generous donations anonymously, but also by how little they expect in return. “Some of our biggest donors who are anonymous, when I asked them what they wanted, they just said, ‘I don’t know, maybe some tickets once in a while.’ It’s just incredible how enthusiastic and supportive the community has been.”

A Sense of Arrival

Each recent season has seen the introduction of another piece of the Bowl’s master plan. Ever since the Roman-spa like bathrooms rolled out in 2004, there have been new things to look at and enjoy along with the music and the company. This year is no exception, and visitors this weekend can look forward to seeing the beginning of the Bowl’s latest renovation, the Angie and Stephen Redding Main Gate. Although it will not be finished in time for opening night on Saturday, the “sense of arrival” that Bowl organizers are looking to create with it should be palpable enough.

Hearing this phrase-“a sense of arrival”-from both Scranton and Dore, I was struck by the extraordinary persistence of this core group who have stayed with the Bowl through the years, watching and learning from the various masters who have come and gone during their tenure. Under the leadership of the current board, there’s no longer any question about what will happen next. Sam Scranton remarks with pride that renovations continue apace, with no lost seasons and no blown budgets after more than 14 years of fundraising and several phases of building. Unlike so many other big projects, here and elsewhere, the Bowl renovation has stayed steady on the course as it was originally set, and a lot of that has to do with the dedication of those who have assumed its stewardship.

With Duran Duran in the house this weekend, there’s no question that there will be plenty of excitement in the air. As for the rest of the season, Moss Jacobs says we can expect “many more big announcements soon.” And in the future, we can look forward to more years of the same, big-league acts in a (relatively) small-sized venue, because, thanks to the Santa Barbara Bowl Foundation, Moss Jacobs, and Nederlander Concerts, the Bowl has arrived.