Ann Diener’s Cathedrals of Commerce

At Edward Cella Art + Architecture through November 2

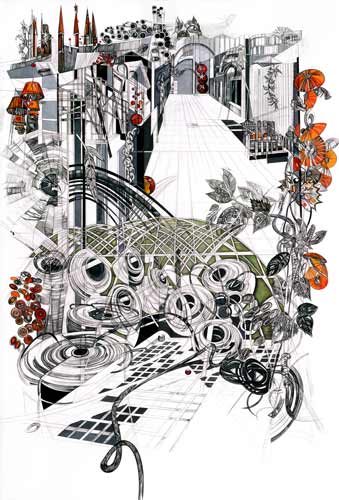

As often as they appear on the roadside, the giant greenhouses of industrial agriculture just don’t stand out anymore. Though they’re still growing larger and more technologically advanced by the year-and indeed, some futurists deem them the wave of the future where feeding the world is concerned-it’s been some time since greenhouses have turned many heads. They’ve been turning Ann Diener’s, though, and her gaze is intense. Long fascinated by modern agriculture, the Santa Barbara artist has created 10 new drawings on various scales, each with its own striking complexity. The series expresses her view of the process that’s brought the industry from subsistence farming by calloused hands and little else to almost completely mechanized operations encased in structures both sprawling and towering. These clean yet cacophonous visions of nature’s coexistence with artifice are now on display at Edward Cella Art + Architecture.

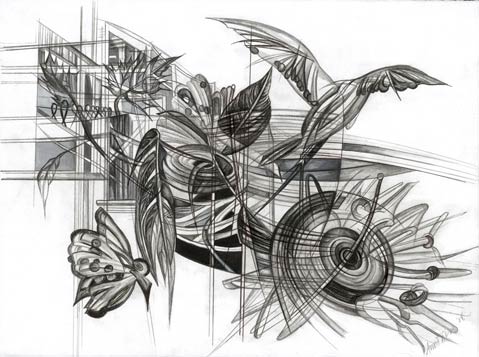

The exhibition, Cathedrals of Commerce, invokes more than enough grandiose architectural elements to merit the name. Walls, ledges, latticework, spires, and glass panes crowd the frames; soaring ceilings spread out up top while the asymmetrical grid lines of an unpainted black-and-white Mondrian etch the floors. Some of these inert components possess a comic book’s futuristic aesthetic, while others feel like yesterday’s vision of tomorrow. Many are pleasing individually, but there’s an undeniable harshness to their agglomeration: each edge juts outward at its own angle as dozens of distinct vanishing points struggle for dominance of perspective. Meanwhile, several hard-to-identify design motifs-perhaps cylindrical discs, perhaps coils, perhaps abstract vortices-reappear in picture after picture, sometimes in teeming numbers. Before considering any individual component, the viewer of these works must allow time simply for the visual noise to settle.

But an aggressive rendering of the built environment is only part of Diener’s concept. Scattered across these layers of panels, beams, and columns lies a biological stratum composed of just about everything one finds in nature, and none of it rigidly angular: insects, leaves, berries, spiders, roots, and honeycombs. Given the artist’s sparing, contained use of color, identifying whether any given element belongs to the biological domain or the synthetic one isn’t always a trivial task, but that may well be the idea: at the same time that humankind’s innovation advances into nature, nature advances into it.