Around the World in Three Vinyls

Curious Music

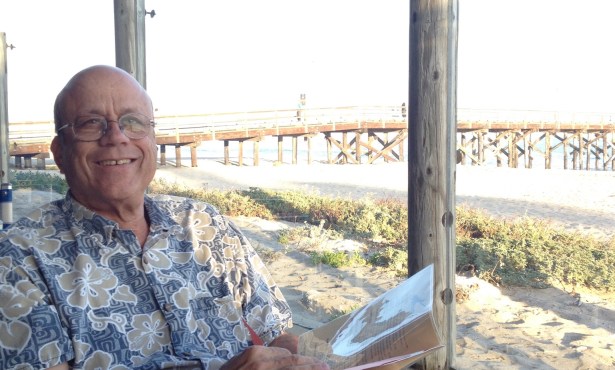

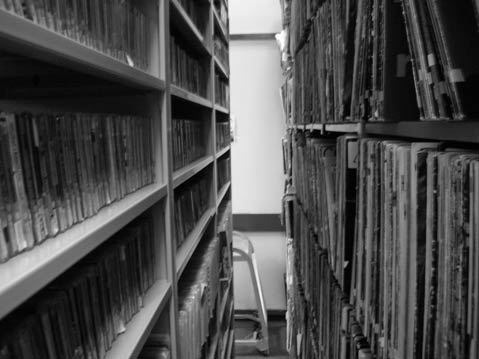

Between KCSB’s lobby and its FM control room sit eight heavy rolling racks, some twice the height of a tall man. Roughly half the shelves brim with CDs, and the other half sag under the weight of thousands of crowded vinyl albums. This is the KCSB music library, a formidable cavern of genres, subgenres, sub-subgenres, and musical curiosities that can’t be pigeonholed into any category no matter how fine-grained the distinction.

For many of the station’s DJs, this is an invaluable resource, a cache of the raw sonic artistry, some of it undeservedly forgotten and some of it deservedly forgotten, from which the most compelling freeform radio is forged. For others, those who program entirely from their own collections or don’t play music at all, the library barely even exists. That, I would submit, is a shame, as there’s much joy to be found—and some pathos—in spending a few hours browsing the stacks and seeing what emerges.

Though the music library is technically broken into separate sections by broad style—rock, jazz, blues, world, electronic (here called “RPM”), hip-hop, soul, classical, and spoken word—you can’t really enter the KCSB music library looking for something specific. While you might find the one record you’re looking for, the odds aren’t in your favor, and you’d do much better to open yourself up to all the unforeseen and indeed unforeseeable possibilities wedged in there. In an attempt to document the mystery and wonder of the music library, I here make my first journalistic foray into the deepest, darkest corners of the vinyl shelves, in search of the sort of stuff that makes it such a delightful place to browse.

I haven’t yet traveled to Japan, but when I do, I’ll organize the trip around visits to its every major jazz club. Friends wonder why I would do this instead of going from shrine to contemplative shrine or high-tech toilet to outlandishly high-tech toilet. They don’t realize that Japan has actually long harbored a thriving jazz culture. Yes, that doesn’t sound like it makes sense. “Jazz and Japan shouldn’t mix,” says All-Japan: The Catalogue of Everything Japanese. “After all,” he goes on, “the essence of jazz lies in improvisation—a concept largely absent from both traditional Japanese music and Japanese society as a whole. Japan may adapt, but it does not improvise.”

But records like the Terumasa Hino Sextet’s Fuji, a 1972 release in Catalyst International’s “Jazz from Japan” series, give the lie to that assumption. Like most of the Japanese jazz I’ve heard, Hino’s wailing trumpet and the studied laid-backness of his rhythm section are both as technically proficient as—and, in fact, often more proficient than—a lot of U.S. jazz groups I could name. But there’s still something inexplicably different about it—an otherness that arises not from the application of cheesy East Asian clichés by way of shamisen strings or shakuhachi flutes. The sound itself convinces me of jazz historian Dan Morgenstern’s assertion on the album’s liner notes: “Japan is a country where interest in and appreciation of jazz is greater than anywhere else, including Europe. Even so, the music on this record may come as a surprise, for we haven’t really heard enough of the sound being created across the Pacific.”

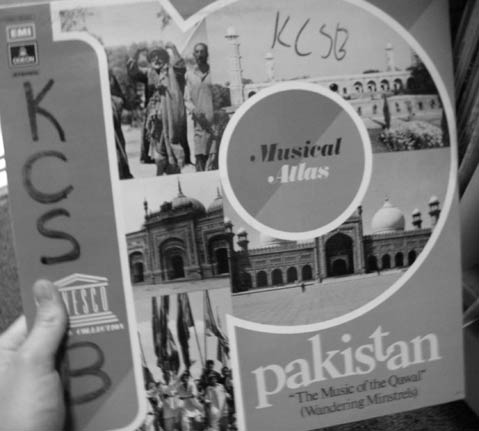

Continuing to flip past sleeve after sleeve, I came across the colorful cover of Pakistan: The Music of the Qawal (Wandering Minstrels). The realization that I had never before knowingly heard Pakistani songs, let along from wandering minstrels, gave me pause. I was also surprised to see that the album was put out by the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization, better known as UNESCO. They don’t make the news very often these days, but, as I understand UNESCO’s purpose, they go around designating various cultural entities as important, as vital, as candidates for the humanity’s vigilant preservation.

Records like this were evidently one way they doled out their imprimatur in 1977. It’s part of their “Musical Atlas” series, which advertises itself on the back cover as also having captured native music from places like Algeria, Benin, Cambodia, “Dahomey” (now Benin), and “Viet-nam” (now Vietnam). There is a certain museum-exhibition quality to records like these, a feeling that their creators took on the quixotic task of somehow “objectively” documenting the ancient, traditional musical ways of the still-pure corners of the globe. The dry trilingual notes on the album’s inside cover support this. But the music itself, a dense braid of vocal and multi-instrumental drones and cries, turns out to be a fascinatingly abstract sonic experience. It’s abstract, at least, to a listener who doesn’t understand the language; the songs themselves seem mostly to be prayers. Perhaps that just makes it even more interesting.

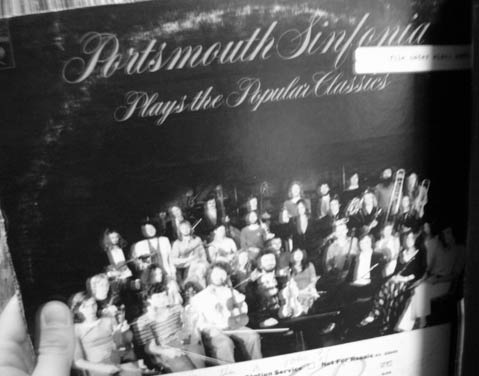

An altogether different brand of density came in the form of the next album I happened across in the library, the Portsmouth Sinfonia’s Portsmouth Sinfonia Plays the Popular Classics. Why would I take this off the shelf? At first glance, it looks like nothing more than one of those cynical, anodyne releases that drains classical music of its essence, gets sold to someone’s grandparents in 1960, and is condemned to eventual dusty damnation in a bin at Goodwill. But upon closer examination, things are much more askew. For one thing, there are an unusually high number of players on the cover, and they don’t look anything like normal symphony orchestra members. In fact, they’re downright ragtag, glazed-eyed caricatures of 1970s slackers bearing violins, trombones, flutes and such as if they didn’t really know what they were. What’s the story?

I admit to cheating a bit here, in that England’s Portsmouth Sinfonia is not completely unknown to me. Squint at the upper right of that musical shambles on the cover and you’ll notice an ethereal, slightly balding figure bearing a clarinet. Why, it’s none other than ambient music inventor, visual artist, record producer, and all-around cultural figure Brian Eno, who’s space-alien look probably owes to the fact that, at the time of Popular Classics’ release, he was still playing synthesizers in the off-kilter rock outfit Roxy Music. Being an insatiable, irrational fan of all Eno has done, I naturally knew about his time as the Portsmouth’s clarinetist, and how neither he nor anyone else in the Sinfonia quite knew what they were doing. This was a take-all-comers group, one that refused to turn anyone away for reasons of skill alone.

In the album’s notes, Eno himself writes, “I notice that many of the more significant contributions to rock music and, to a lesser extent, avant-garde music have been made by enthusiastic amateurs and dabblers. Their strength is that they are able to approach the task of music making without previously acquired solutions and without a too firm concept of what is and what is not musically possible.” Thus do you get, specifically when listening to the Sinfonia’s renditions of the most well-known bits of The Nutcracker Suite and Also Sprach Zarathustra, the feeling that no other process could have achieved such subtly shifting, heartfelt, yet stochastic results.

To get grand for a moment, maybe this is also what KCSB itself allows. Since the station accepts and is home to DJs with the whole range of pre-existing radio experience from zero to lots, it never adheres to ossified concepts of what is and is not possible in radio and the aural media as a whole. Enthusiasm is what counts. If you’ve got enough of it to put on a show revolving around, say, Japanese jazz, Pakistani prayer, or the United Kingdom’s amateur symphonics, nothing’s standing in your way. KCSB takes all comers—and they get full access to the music library.