Wandering Mountain Drive’s Wacky Hermitage

Despite Disaster, Theodore Roosevelt Gardner II’s Sculpture Garden Lives Whimsically On

Ever since the naked grape-crushing and pioneering hot-tubbing days of the 1950s, Mountain Drive has been celebrated as Santa Barbara’s wackiest neighborhood. But it wasn’t until the early 1990s that the road’s most visibly bizarre resident moved to town and proceeded to build a brightly colored house perched above Parma Park and to erect countless crazy sculptures around his property for all to gawk at.

This is the tale of Theodore Roosevelt Gardner II, whose home—known simply as “The Hermitage”—was consumed by the Tea Fire in 2008, but whose wild artistic spirit and wildly spirited art continue on. Today, while most of the sculptures remain standing but scarred and his new home arises slowly from the ashes, Gardner’s legacy is best remembered in The Hermitage Santa Barbara at 20, a photography book laden with anecdotal memoirs that Allen A. Knoll Publishers released earlier this year.

“It’s not much, but it’s home,” Gardner tells me one morning in a subdued, ironic tone that persisted throughout our stroll around his 18-plus acres, a place where garden jockeys are buried like China’s terra-cotta warriors and the remnants of a crashed UFO abut citrus trees, rare cycads, and even a redwood grove. “We wanted to build a little retreat,” he said of buying the property 20 years ago, after having visited Santa Barbara from his Palos Verdes home for nearly four decades. “It was too cheap to be true, and then I discovered why.” The “why” was partly because of the property’s steep slopes, but also because of stringent city regulations and vigilant neighbors who objected to almost everything Gardner proposed. Was he too weird for Mountain Drive? “You’d be surprised,” said Gardner, whose home is most easily located by looking for the bent-over-bicyclist mailbox. “If you’re different than they are …”

In time, his house took shape, and he began collecting and creating odd works of art, some of it beautiful, much of it gaudy, all of it seemingly tongue-in-cheek. “Now they park their cars and stare,” he said dismissively of his former critics, who couldn’t do much at all about Gardner’s penchant for sculpture. “You don’t need a building permit for sculpture, fortunately, or we’d have a lot less stuff.”

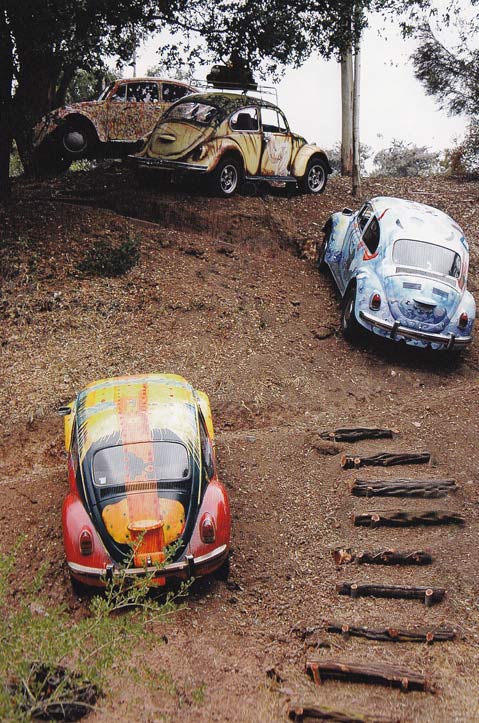

There’s a garden of composers’ busts, a circle of presidents’ faces, two chess players stuck forever in limbo, a fat Fanny Farmer, a majorette who’s skewered the head of a soldier, and, in homage to Rodin, “The Slow Learner” (compared to “The Thinker”) and “The Wives of Calais” (instead of the “The Burghers of Calais”). There are discarded but vividly adorned VW Beetles here and armies of nearly 200 tossed-aside bicycles there, dozens hanging from a torched tree, others aligned to make the property’s fence. The fire destroyed many of the animal sculptures and erased the children’s playhouse, but a post-blaze looter was responsible for the loss of the burger man. Another survivor was Gardner’s studio, which he built when he realized that it would be cheaper to make his own art than to keep buying it. Designed by “brilliant, unsung” architect Jerome Landfield, the upside-down children’s top with glass walls remains a centerpiece of The Hermitage, an example of whimsy come to life. Meanwhile, the property’s rare plants are creeping back to life, promising to bring back nature’s own art in due time.

Despite the obvious allure a visit to this bizarre land would have for anyone interested in creativity and imagination, Gardner only shares it with his family, which includes eight grandkids, who’ve been immortalized in a front-yard sculpture. “It’s a personal garden,” he pledged, later adding with paradoxical pleasure, “I don’t really want people around, but we keep getting all this publicity.” That includes a recent photo spread in the Los Angeles Times and the publication of the book, which is just one of nearly 40 that Gardner—a former TV writer—has penned over the years under various aliases, from fictional detective novels and love stories to nonfiction works on Lotusland and the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden.

By the end of our walk, Gardner seems like a perfectly normal fellow, for why wouldn’t one fill their gardens with art if they had the means to do so? But why not share it, I wondered? Then, while thumbing through the book in between writing these very sentences, I came upon the page filled with photographs of the composers’ busts. There, in a bubble floating above the head of Arnold Schoenberg, appeared an answer. “If it is art, it is not for all. And if it is for all, it is not art.” In the case of The Hermitage, that’s as perfect an explanation as any.

4•1•1

The Hermitage Santa Barbara at 20 (Allen A. Knoll Publishers; 2010) features the writing of Theodore Roosevelt Gardner II and photographs by Susan Levin, Stephen G. Schott, Robert Haller, Mary Andrews, Marlene Khoury, Nancy Vivrette, and Wayne McCall. Visit knollpublishers.com to purchase.