Let the Sun Shine In

Inside Old Mission Santa Barbara's Plight to Bring Back Solstice Sunlight

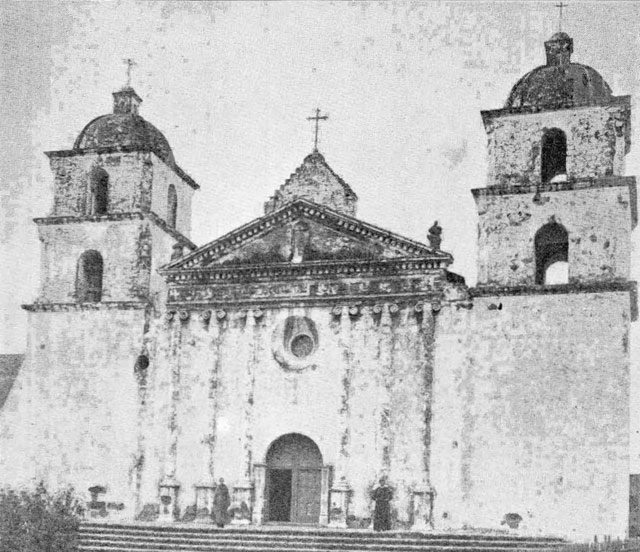

On the dawn of the winter solstice, the sun rises in the east above the mountains of Montecito, casts hues of golden pink on the crags of La Cumbre Peak, and sparkles across the swells of the Santa Barbara Channel. Sunlight creeps through the oak trees and into the canyons, melting the frost on the meadows of yesteryear and lawns of today, eventually cresting the Riviera and shining upon the towers of Mission Santa Barbara, a symbol of our town since its founding.

As the sun continues to rise, it splashes rays of light down the church’s central aisle, and as a full house of observers stare toward the altar, a powerful beam burns through the rose-shaped window on the mission’s facade. Then, for a few magical minutes, the solstice sunlight settles on the Chumash-built tabernacle, whose inlay of abalone shell and three polished mirrors reflect blasts of light back toward the congregation. No matter which spirits you hold dear — be it Jesus Christ of the Catholic Church or Kakunupmawa, the Chumash people’s notion of the winter solstice — the twinkling intersection of celestial orbits and manmade architecture is bound to trigger a sense of wonder.

“As the parishioners sat there and witnessed the illumination,” explained Ruben Mendoza, an archaeology professor at California State University, Monterey Bay, who’s spent the past decade researching illumination windows throughout Spanish-built structures in the Western Hemisphere, “it had to inspire them and make them feel part of something much bigger.”

Mendoza first stumbled upon the architectural phenomenon at Mission San Juan Bautista in the 1990s; he was further convinced these elements were not coincidences during a summer solstice illumination at Mission Carmel in 2003. Mendoza has since identified “sacred geometry” in 14 of the 21 California missions — including all three in Santa Barbara County, if you include the original site of Lompoc’s La Purísima prior to its 1812 relocation — as well as in the East Canon Perdido Street chapel of El Presidio de Santa Bárbara.

Based on his own findings, as well as those from a growing body of researchers throughout the Southwest, Mexico, and the rest of Latin America (including the most recent discovery in Lima, Peru), Mendoza believes that as many as half of the more than 100,000 structures built from 1521 to 1821 during Spain’s colonial era feature some form of calendar-based architecture, a revelation that’s rooted in very technical astronomical measurements but manages to trigger grander, sometimes controversial notions of spirituality and faith.

When it was reconstructed in 1820 — but likely before then, too, as the original’s axis was aligned similarly — Mission Santa Bárbara offered one of the more glorious winter solstice illuminations, but the tradition was slowly forgotten, as it has been in most sites. So during another renovation in 1952, the church’s pipe organ — which had been donated in 1905 by Andrew Carnegie — was set across the back wall of the choir loft, thereby blocking the circular window and ending the phenomenon.

Today, the mission is moving to let the sun shine back in, starting last month with the replacement of the former solstice window with a rose-shaped one, and continuing through this year with a fundraising campaign aimed at restoring and reconfiguring the organ. The ambitious hope is that, by December 21, 2012, the winter solstice sunbeams will once again enter the church, shine on the Chumash tabernacle, and inspire all who come to bear witness to the illumination.

“We’ve lost the light,” said Tina Foss, the mission’s museum director and cultural resource manager, who’s spearheading the project. “We want it back.”

Holy Light?

A Catholic himself, Mendoza appreciates the light as a reaffirmation of his own faith and has witnessed others succumb to its power, as well. “I’ve literally seen people fall to their knees or shout ‘Hallelujah!’ when they see this during Mass,” said Mendoza, who’s been an archaeologist at San Juan Bautista since 1995. “It’s like an apparition.”

Awe aside, Mendoza believes that there are more practical reasons to explain why the Franciscan friars living in the wilds of Alta California in the late 1700s and early 1800s would have incorporated complicated calendrical designs in the construction of churches: primarily, to keep track of the many holy days observed by the Catholic Church, and with the added benefit of converting natives who already attributed mystical and religious meanings to the winter and summer solstices.

“There are hundreds of feast and saint days, so how do you maintain them without a system?” Mendoza asked during a telephone conversation in early December, as he was readying for the San Juan Bautista solstice, which has become quite a community event. “I believe that system was introduced into America and used in the frontier missions in order to literally keep track of the accurate observance of Easter and a host of other feast days.”

That explanation doesn’t spark much controversy, but Mendoza’s theory about the architecture as a religious conversion technique treads on more sensitive ground. “How do you convey a message for people who have a very different worldview and for whom only the sun and heavens are god?” asked Mendoza. “These [solstice events] become teachable moments. I see illumination of churches in much the same way.” In other words, people who are already worshiping the sun and aware of the winter solstice’s annual importance would be mighty impressed when the new religion in town was able to light up the altar on the holiest day of the year. Of course, it could also backfire. “When the light didn’t come, as a result of winter conditions, it might have inspired fear and dread in the coming year,” admitted Mendoza.

His ideas fetch fiery reactions from opposing directions: Some Catholic diehards refuse to believe that the missionaries would have strayed from the traditional means of spreading the gospel, whereas those critical of the church’s role in conquering indigenous peoples are reluctant to consider that the friars may have employed a more peaceful and accommodating strategy in pacifying the natives.

But Mendoza doesn’t budge and cites the increasingly accepted idea that Christianity has a long tradition of conflating its beliefs with those of “pagans,” particularly in equating the son of God with the sun of our sky, a strategy used as far back as Roman times. He explained, “Contrary to much of what has been said, especially in the revisionist literature, I do believe that the church went to great lengths to accommodate indigenous beliefs way beyond what’s been accounted for.”

The Old Mission’s Foss, a walking California history encyclopedia who’s also taught a class in Native American studies at Santa Barbara City College for decades, is a proponent of this new way of thinking, one that is largely supported by the written evidence of the mission era. She also believes that, to many Chumash and other California natives, the Catholic Church simply offered another way to access the divine, but not the only way, as many continued their traditions of worship while adopting Christian practices. In return, the friars allowed their neophytes to occasionally syncretize otherwise competing beliefs.

Nowhere is this idea more visible than in the Chumash tabernacle, which was built in the 1790s and has remained pretty much the same ever since (despite some scoundrel stealing a wooden arm from the piece during the I Madonnari festival in 2010). In addition to the abalone inlay and the mirrors that are thought to have been an integral part of the solstice phenomenon — the light coming off the three mirrors, Mendoza suggests, may be a visual metaphor of the Catholics’ Father/Son/Holy Spirit trinity — the vibrantly decorated redwood altarpiece features plenty of red ochre-like paint (which is the sacred color of Chumash shamanism), a mother-of-pearl Jerusalem cross (which was imported from the Holy Land by Franciscans), and icons from the Christian crucifixion saga that were likely copied off of an old gazette drawing from inside a cathedral in Salamanca, Spain. Altogether, said Foss, “It’s a very interesting cross-cultural piece.”

After the 2010 vandalism, the Chumash tabernacle — which is the centerpiece of the only Native American–built altar to survive from California’s mission era — was tucked into a hard-to-see corner of the mission church. But next month, it will be on full display once again, as Foss converted her own office into a special showcase for the altar as part of the mission museum. When it comes time for the solstice light to return to the mission, it’s probable that the Chumash altar will, at least temporarily, be returned to the front of the church, ready to accept the sun and spread it for all to see, as it had done for more than 150 years.

Rose-Shaped Glass and Musical Magic, Too

Putting the tabernacle back is the easy part, especially since it has wooden handles that still work more than two centuries after it was crafted. The bigger challenges will be reopening the window to the church, which has required the replacement of the old window — the cracked corner of which was actually what launched this entire restoration effort — and the reconfiguring of the pipe organ, which is expected to cost at least $150,000.

The first step in the process was a bit of archival detective work to determine what the original window looked like. The 1952 window’s design of a cross connecting four panes made no sense for letting direct sunlight in, so Foss, Mendoza, and a team of historical experts at Chattel Architecture in Sherman Oaks investigated old photographs to find the former pattern. An 1870 shot by Carleton Watkins, when subjected to filtering and focusing, revealed a rose window, where petals surround a circular center pane. Judson Studios, near Pasadena, was hired to craft the replacement window, and two weeks ago on December 22, the old window was taken down and the rose-petal one was installed.

That leaves the reconfiguration of the pipe organ, which is historic in its own right, having been donated by “Andrew Carnegie and the People of Santa Barbara” in 1905. Up in the loft one afternoon in early December, Roy Spicer, the mission’s liturgy and music director, explained how sensitive the organ is to temperature and movement, but he also pointed to a blower that was held together with duct tape. “It’s not really a great sounding organ,” admitted Spicer, explaining it needs work even aside from the solstice window project. “It really doesn’t compare to some of the other organs in town.”

It’s not the first time organ restoration has been recommended. Eight years ago, Keith Paulson-Thorp, the mission’s former music director, who now works for a church in Delray Beach, Florida, suggested the organ and loft be rearranged to reflect the original layout and even brought in an organ expert, who had ideas of how to make it look and sound like an organ with 19th-century Mexican origins. “In spite of its size limitations, the mission organ has some very satisfying attributes, including some really gorgeous stops, and it is certainly large enough for the room with its superior acoustics,” said Paulson-Thorp. “I always loved playing it, and there wasn’t much repertoire that I could not make work on it. The current chambers are not very intelligently thought out, however, and there is a lot of wasted space.”

Spicer is hoping that the reconfiguration will open extra room in the tight choir loft for more instruments and singers, allowing the mission to be used as a classical music venue. An outreach to Santa Barbara’s vast music-loving community might make raising the big bucks a tad easier than if it were simply a parish effort. Both Justin Rizzo-Weaver of CAMA (Community Arts Music Association) and Joan Rutkowski, whose Esperia Foundation once put on concerts there, see potential for the venue. “Personally, I find it an acoustically superb venue and a great place for concerts, especially vocal music,” said Rizzo-Weaver, who used to sing there. Added Rutkowski of her experience, “The ambiance and acoustics of the Old Mission Santa Barbara were special, inviting, and very appropriate.”

The Unsolved Mysteries

Assuming the sun is shining on that glorious solstice-to-be and everything lights up as planned, there’s certain to be a celebration and lots of congratulations to go around. But as the evidence for these illuminations continue to grow each year, two big mysteries remain: Given that the frontier friars produced extensive records and detailed correspondence about all aspects of missionary life, why hasn’t anyone found a written record of these architectural techniques? And, perhaps more intriguingly, why were these events simply forgotten?

There are a few answers to the former question. According to Jarrell Jackman, the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation’s director, who witnessed the Presidio’s illumination this past December 21, one reason is that those records simply have not been found yet among the 25 million pages of documents located in archives throughout California, New Mexico, Mexico, and Spain. “It probably is written down somewhere but has yet to be found or looked for,” explained Jackman, calling the documentation a “needle in a haystack.”

But Mendoza isn’t even sure the missionaries would have written it down. “They weren’t into the PR end of it,” he said. “They weren’t going to wave the banner and say, ‘This is unique.’ They just did it.”

As to why these reportedly awesome illuminations slipped from the collective memory, Mendoza believes that much information faded when the Mexican government took over from Spain in the 1830s. “At least for California,” said Mendoza, “a lot of this understanding died with the Franciscan missionaries during the period of Mexican secularization.” When new missionaries eventually returned, they were disconnected from the illumination tradition. “Not to say that people haven’t seen this since,” said Mendoza, “but rarely did they equate it with anything significant.”

Come December 21, 2012, though, Santa Barbarans should hopefully be able to see the significance of the winter solstice illumination in our own mission. And even if you aren’t down with the religious or heavenly implications, you can at least take pride in the historical ones. Explained Foss, “To reopen that window will be a true restoration of the original architecture of the church.”

Mission Maintenance

The return of the winter solstice phenomenon is a small part of Mission Santa Barbara’s ongoing renovations, which will probably cost more than $1.5 million and are partly being funded by a $650,000 matching grant from the National Park Service’s Save America’s Treasures program as well as donations from the Santa Barbara Foundation, the California Missions Foundation, and the Stinehart family. Here are some other needed repairs:

• Structural improvements to the crypt beneath the church floor, where lie some of the oldest and most important graves.

• Structural improvements to the convento wing; its sandstone walls are being eroded by water seepage from the ground.

• Hydrology studies to determine structural water impacts.

• Replacement of the brickwork on the lavandería.

To contribute to these causes and/or the solstice window reopening, see santabarbaramission.org.