L’uomo e il suo ambiente nel duemila

Humanity and Its Environment in the Second Millenium

I was fortunate to work with Robert Huttenback, during his tenure as UCSB chancellor, on an idea that seemed to offer a second great step for the university following the establishment of the National Science Foundation-sponsored Institute for Theoretical Physics. It began one day in 1982, when a contingent of leading citizens of Venice, Italy, arrived on campus, led by Piero Mainardis, one of that city’s best-known architects, and including various dukes and duchesses, public officials, and members of the faculty of the University of Venice.

The delegation had recently written to the University of California’s president in Oakland, asking whether University of California would assist in developing an International Center for Environmental Studies on Sacca Sessola, one of the islands in the Venetian Lagoon. They said that Venetians looked to the United States for leadership in science, technology, and environmental improvement, and especially to the state of California, which they believed to be at the forefront of America’s leadership in these fields.

The proposal was for a partnership between UCSB and the University of Venice’s environmental scientists, the latter led by Professor Angelo Orio, a chemist. We would provide expertise where it was not available in Italy, and the Venetians and the city of Venice would provide the place and assist with the funding. The request filtered down to each of the campuses and intrigued then-UCSB Chancellor Robert Huttenback.

He sent it over to me, as I had recently become chairman of the university’s Environmental Studies Program. The timing seemed perfect because a major emphasis was developing at UCSB in the applications of NASA’s satellites to study Earth’s ecological systems and environments from space. Faculty from Biology, Environmental Studies, and Geography were among those taking the lead. NASA and other federal agencies were beginning to provide funding for research related to these concerns, and the then-new idea of a global ecology was assuming greater importance in the minds of ecologists. An international institute to pursue these global questions did not yet exist, but it seemed inevitable that one would get going somewhere in the not-too-distant future.

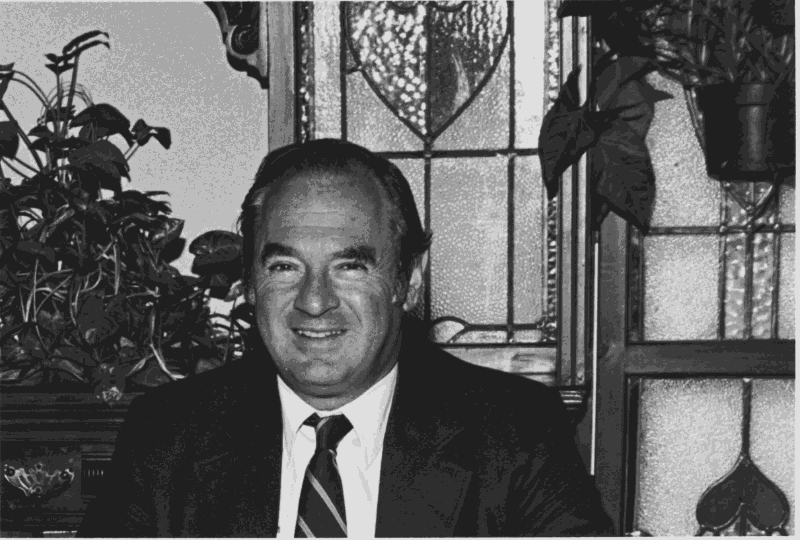

With worldwide concern about the environment growing rapidly, and given that UCSB had one of the few environmental studies programs in the nation, Huttenback saw this as a natural extension of his efforts to turn UCSB into one of America’s leading universities. He was devoted to intellectual quality across all disciplines and, as with the Institute of Theoretical Physics, he realized that an internationally renowned institute or department in one area, especially one that dealt with a major growing interest around the world, could help UCSB directly and also help to foster excellence across the campus. As a historian doing what he could to promote science, the interdisciplinary aspects of the new institute were especially appealing to Huttenback. The request came at an opportune time, just as Jack Estes of Geography, several other faculty, and I were seeking a site for what would be the world’s first international center for the study of global environmental issues.

We had come to understand that as the Twentieth century was ending, our technological civilization was changing the environment at a global level, and new tools were, for the first time, making it possible for us to study and respond to the global changes.

The Venetians explained that Sacca Sessola had numerous unused buildings, which would make the island all the more suitable as the campus of the new institute. We agreed. Indeed, we thought no place in the world would be better than Venice for this international institute. This was still the time of the USSR, and with concern about global environmental problems just beginning, it seemed important that communication extend to both sides of the Iron Curtain. Venice’s long history as a center for international trade and for communication of ideas in the arts and sciences, coupled with its location on the Adriatic Coast, seemed ideal.

This was also an opportunity for Venice to once again play an important role on the world’s stage as an international center for communication, for the best that civilization can offer, as a symbol of the height of human creativity in contact, and in harmony, with nature.

Thus began a cooperative venture that involved the University of Padua in addition to the University of Venice and UCSB. Huttenback’s lively enthusiasm encouraged everyone to get through the inevitably intense and often difficult series of negotiations, involving not just citizens, university faculty, and government officials of Venice, but extending to Italy’s central government. Three years of hard work went into this attempt to establish the institute, culminating in an international conference, “Man and His Environment in the Year 2000,” held in Venice in 1985. Nobel Laureate physicist Roman Prigogine gave one of the keynote speeches, and participants came from 70 nations. Discussions were held broadly with leaders in environmental sciences, including the president of the Ecological Society of America. Out of this came a book, Changing the Global Environment: Perspectives on Human Involvement, published in 1989 by Academic Press, New York.

Returning to Venice for that conference, I was reminded that no one can live in Venice without being an “environmentalist.” For here, perhaps more than anywhere else, the beauty that human beings had created over the centuries was touched by continual environmental changes: the daily tides that flushed wastes from the city out into the Adriatic and brought fish, and nutrients for them, into the lagoon; the seasonal changes, such as the aqua alta of winter storms that flooded famous St. Mark’s square. What better place, it seemed, for people from all over the world to come together to contemplate how we and our environment, having affected each other in the Twentieth century, would travel together into the Twenty-first?

During the first three years of discussions and development, everything looked good for the establishment of the institute. However, this proposed international environmental institute lacked two things that the Institute for Theoretical Physics had: an assured external source of funding, and a scientific field with several centuries of great prestige. Although the Venetians offered to help with fund-raising and did provide funds to help with the planning for the center, they were not able to provide large-scale initial funding. Also, the world was just beginning to recognize the importance of environmental sciences and environmental studies, and these were not yet everywhere considered legitimate university fields. And so a strange thing happened.

It was of course necessary that the idea and plan for this international institute be discussed and approved by faculty and administration of the three universities. The University of Padua saw no problems. Oddly enough, it was academic politics at both the University of Venice and UCSB that interceded. At faculty meetings I attended on both campuses, far distant from each other both geographically and in spoken language and many cultural attributes, the simultaneous rise of these attitudes shocked me. Apparently some faculty, who had no interest in the subject and saw no advantages to be gained for themselves, opposed the new and creative idea, and in the end the Venetian International Institute did not come about.

Although I was saddened by the demise of what I and many others considered an exciting and creative idea, I look back on the time I spent with Bob Huttenback as one of the highlights of my career. In my many decades as a faculty member, at UCSB, at Yale University, and at George Mason University, I never met anyone with Bob Huttenback’s wonderful combination of abilities. He could evaluate excellent scholarship and recognize what was going to be important in the future. His hard work and devotion to improving the university, coupled with his enthusiasm and great personal charm, enabled him to raise funds and attract interest widely. It was a privilege to work with him. Thank goodness that the Bren School, developed on the UCSB campus subsequently, provides a place where many of the ideas that were yet unborn in the early 1980s have blossomed.

Daniel Botkin is professor (emeritus) in the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He joined the UCSB faculty in 1978 and was chairman of the Environmental Studies Program from that year to 1986. Professor Botkin remained on the faculty in that program and in Biology until 1999, when he became emeritus. He continues to be active in research and writing. His forthcoming book, The Moon in the Nautilus Shell: Discordant Harmonies Reconsidered, will be published this August 22 by Oxford University Press.