Hooked on Frack?

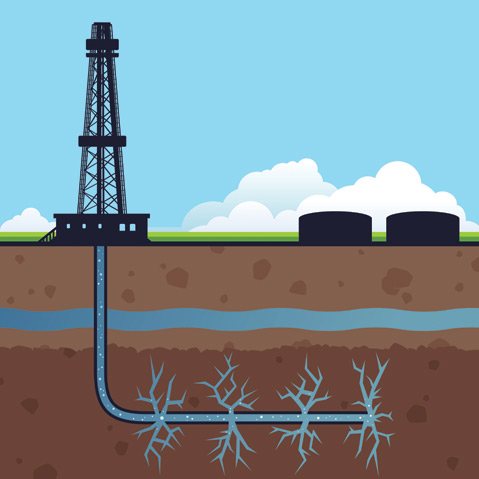

Where Oil Companies Could Be Fracking in Santa Barbara County

By now, due to footage from the northeastern United States of methane-soaked wells catching fire and kitchen faucets spewing chunky brown water, “fracking” has become a bad word nationwide. It’s industry slang for hydraulic fracturing, a practice developed in the 1940s and revolutionized in the 1990s, in which oil companies extract hard-to-reach fuel resources by drilling deep holes, dropping mini bombs, and then pumping in a cocktail of water, sand, and toxic, safe, and unknown chemicals to break up the earth and release the oil. The problem is that the fluid doesn’t just evaporate. Instead, it’s contaminating farms, wells, and aquifers, and has the potential to poison the water supply.

With conventional drilling options drying up fast, Santa Barbara County could be a hotbed for a new wave of fracking, thanks in large part to the underground shale formations that can be tapped by the method. That realization, triggered by evidence of fracking near agricultural land in Los Alamos, caused the Board of Supervisors in December 2011 to mandate that all future fracking practices on unincorporated county land be reviewed and approved. But finding out where fracking occurred prior to that date is nearly impossible because the State of California does not require companies to reveal the location or number of wells. Even more troubling for many people is that neither the state nor the federal government requires oil companies to divulge what they’re pumping into the soil, a mixture that investigative reports have discovered may include everything from run-of-the-mill toxins like lead and formaldehyde to known cancer causers arsenic and benzene to radioactive substances such as radon and uranium.

Set against a backdrop of government-approved confidentiality, a landscape of undisclosed sites, and a very real set of lethal stakes, it’s no wonder that rumors about where fracking might be happening are swirling. So in an attempt to cut through the haze — and based on the latest academic publications, industry communications, and anecdotal accounts — what follows is a quick tour of where fracking could have and may one day occur in Santa Barbara County.

Wine Country

The buzz about fracking in Santa Barbara County started in early 2011 when officials learned that Carpinteria-based Venoco, Inc. was using the method on two wells 11,000 or so feet deep off of Highway 135 near Vandenberg Air Force Base. Extra controversy ensued when it was discovered that the fracking occurred on leases without the knowledge of property owners.

One of those was Steve Lyons, whose Kick On Ranch features a vineyard of riesling grapes that are coveted by such celebrated vintners as Tatomer, The Ojai Vineyard, and Municipal Winemakers. Lyons claims that Venoco’s fracking endangered his grapes, well water, and livelihood, explaining that a pipeline to dispose toxic liquid waste ran through his vines. He believes that the water his family drinks is unsafe and would like to see further cleanup.

Though the science is not yet conclusive on whether food and drink made from agriculture exposed to fracking fluid is unsafe, the fracking cleanup business has blossomed in hopes of a second-wave oil rush, with one Texas waste company purchasing a fracking cleanup company for $1.3 billion.

A few miles south of the Kick On Ranch lies Bedford Winery, whose owner Stephan Bedford believes that the nearby fracking jobs are a threat not only to his grapes but to the entire Central Coast wine industry, and worries that a higher-than-usual amount of truck traffic on Highway 135 is related to increased oil production. According to attorney Nathan Alley of the Environmental Defense Center, the increased traffic might be related to cyclic steam injection, another form of advanced oil recovery designed to get at hard-to-reach shale oil that uses brine water that may be filled with toxic substances.

When asked about the suspicions of Bedford, Lyons, and Alley, Venoco spokesperson Lisa Rivas would only confirm that the company had fracked “three wells in north Santa Barbara County in 2011” and would not provide their exact locations.

Up the road toward the town of Orcutt, the best information on fracking comes from academia. In 2002, scientists from Stanford University wrote a detailed paper in the Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering about the geology and engineering of a Nuevo Energy frack job in the Orcutt Hill Oil Field right outside the city limits. Nuevo Energy is now owned by Plains Exploration & Production (PXP), whose regional headquarters sits squarely in the middle of Orcutt’s quaint old town.

Carpinteria Coast

With more rigs and other operations on the Carpinteria coastline, Venoco, Inc. touts its location atop a rich geological formation known as the Monterey Shale, which the company’s chief, Tim Marquez, told the Oil & Gas Financial Journal offered “the most exciting and promising opportunities at Venoco, and for that matter, the entire industry.” The company — which has admitted to fracking into the Ventura County seafloor off of Platform Gail — is advertising the potential value of the shale’s resources at $1.4 billion, recently posted job offers for shale experts, and, according to promotional literature, has executed a “multi well and multi $100 million” exploration of the formation.

That has Carpinteria residents worried, including former mayor Dick Weinberg and Miguel Checa of the Carpinteria Valley Association. Both report an increase in trucking activity in the Venoco area, which they believe is evidence of new types of drilling operations. Longtime Carp activist Ted Rhodes fears that, if the company does start fracking nearby, it could contaminate the city’s drinking water.

So, are Carpinteria’s concerns premature or prescient? “We do hold a lease offshore of Carpinteria,” said Venoco spokesperson Rivas when asked about plans for the area. “We have no final plans for developing that lease, but we are in discussions with multiple parties.”

Front-Country Foothills

The coast of Carpinteria isn’t the only target for possible fracking. According to the Environmental Defense Center, Occidental Petroleum fracked just a few miles south of the city in the Rincon Hills on May 2011, drilling 8,474 feet and using 360,000 gallons of water. Though Occidental did not reveal its Rincon fluid, the company did disclose some substances used in a frack job last year off the coast of Long Beach: the highly toxic and flammable chemical methanol and the carcinogenic 2-butoxyethanol.

Though the government protects fracking fluid ingredients as proprietary information, the oil-and-gas industry has started to self-report a fraction of its frack jobs through the website FracFocus.org, on which 200 companies have listed 15,000 sites so far. But such information can be incomplete or inaccurate.

Take a FracFocus report by ExxonMobil that listed a site near Highway 154 above Foothill Road in Santa Barbara last January: After several emails to ExxonMobil, spokesperson David Eglinton explained that “the wrong longitude” was entered in the geographical mapping database and that ExxonMobil is not reporting any fracking locations in Santa Barbara County. He clarified that the frack job was actually in Kern County but gave no other information. The Foothill frack job is no longer displayed on FracFocus.

And even the few regulatory agencies that focus on fracking sometimes post inaccurate information. Recently, the Division of Oil, Gas, and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR) showed on its website that Aera had a new water flow well, which can indicate fracking, offshore of Oxnard. Only after several calls and emails to Aera and the state’s Department of Conservation, which oversees the oil industry, was it learned that Aera had sold its offshore interests. The records have since been changed.

Federal oversight is also questionable. Two years after Venoco admitted fracking from Platform Gail, Nick Pardi of the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, which regulates offshore resources, explained, “There are no fracking operations occurring offshore California in federal waters.”

When even the regulators are ill-informed, it’s easy to see why trying to determine which company is fracking with what and where remains a difficult proposition. The steps taken by the County of Santa Barbara should help inform at least this region, and the California Department of Conservation’s ongoing development of fracking rules, which is still open for public input, will also help. But with billions of dollars to be made and plenty of oil needed to make the world go ’round, fracking will certainly continue into the future.