Dogs Versus Hunters in the Backcountry

A Closer Look at the Issues Facing Two Groups of Trail Users

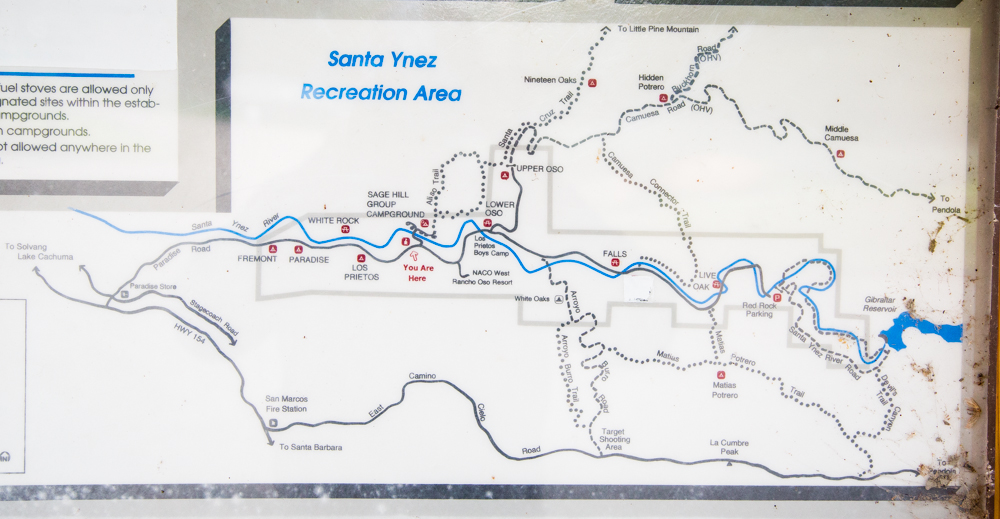

When 25-year-old Nick Krueter and 32-year-old Samuel Lowe got up early on Tuesday morning, January 15, in Brea, California, they were heading up to the Santa Barbara backcountry for a day of hunting. From various accounts, it appears they arrived at the Upper Oso area about dawn and headed up the Santa Cruz Trail to hunt for pigs.

Though not a particularly good area for pig hunting, apparently the nearby private land at Rancho San Fernando Rey is. Stephen Nellis, a hunter and a dog owner, described Santa Barbara County as one of the “top five” spots for pigs. “But more than 90 percent of the land where you’ll find them is private,” he noted. “There’s some thought that some of the pigs may wander off San Fernando Rey and down into the drainage where the Santa Cruz Trail climbs up to Little Pine Mountain.”

Kreuter and Lowe spent the morning somewhere in the vicinity of a small hiker’s camp known as Nineteen Oaks or in the area above it. At some point in the early morning, they decided to head back to Upper Oso. At about 11 a.m. as they rounded a corner, they spotted two dogs heading toward them. According to the Sheriff’s report, one of the dogs barked and acted in an aggressive manner, frightening the hunters enough that one of them took aim and fired, resulting in the death of a 40-pound dog named Billy.

Though the two hunters have not responded to repeated requests to discuss the incident or share their side of the story, the shooting ignited a firestorm of controversy. Many blamed the hunters, with others faulting the dog owner for not having the two animals on a leash. Mostly, though, the incident brought up a boatload of questions: Why hunt so close to a high-use recreation area and on one of the most popular trails in the Santa Ynez River area? Did the pair have hunting licenses? Pig tags? Were they required to have some sort of hunter education? What type of threat would be required for the hunter to take a dog’s life? What type of responsibility does the Forest Service have to monitor either hunters or dog users? Should the dogs have been on leash?

Forest Rules

I sat down with Pancho Smith, district ranger for the Santa Barbara District of Los Padres Forest, to discuss some of these issues. “It was a tragic situation,” Smith explained. “Two hunters on the trail in an area where it was perfectly legal to hunt, a trail runner coming up the trail with his dogs, both off leash, but also perfectly legal to do — an incredibly sad and emotionally impacting thing for both sides.”

“There are restrictions for both when they’re within the Santa Ynez Recreation Area,” Smith added. “Inside it dogs are required to be on leash, and it is illegal to discharge a weapon there, as well.” In addition, in 2011, after receiving complaints from a number of canyon visitors, bow hunting was also prohibited in the most highly used parts of the recreation area where the campgrounds are located.

Outside the area, while hunting is legal during the appropriate seasons (pig season is year-round), there is a prohibition on shooting in Los Padres Forest within 150 yards of a residence, building, campsite, on or across a road or body of water, or in any manner or place where a person or property is exposed to injury or damage as a result of such discharge.

“I’ve always wondered what exactly these words mean?” Nellis questioned. “Do trails count as developed sites or potentially occupied areas where a person or property could be exposed to injury?” No, according to the district ranger.

While it is clear that the hunters were on a part of the Santa Cruz Trail that was outside the recreation area and well beyond Nineteen Oaks Camp, some questioned if it was appropriate for them to be carrying loaded weapons on the way back to their cars, had an awareness that they might meet other users on the trail, or were prepared for such an encounter.

“That brings me to another point,” Nellis added. “We shouldn’t be talking just about what’s legal, but what’s wise. I rarely, if ever, hunt on weekends, and I never, ever hunt except in the designated wilderness areas. Even then, there are some wilderness areas — Manzana Creek out in San Rafael is a good example — where I only go when I know the traffic will be low. I also always go off-trail to do my shooting and keep track of where the trail is so I’m not shooting toward it. That’s basic safety stuff.”

Nellis also emphasized the idea of “positive target identification” — a concept that focuses on shooting only when you are 100 percent sure of your target. “I heard that one of the hunters thought he was about to be attacked by a wild dog,” he said, “but I don’t know of too many wild dogs out there with bright orange collars around their necks. I’ve certainly been spooked by people’s dogs while on the trail, but I’ve never come close to shooting one, especially on a trail where you would expect to see them.”

According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, all hunters are required to have a valid hunting license, and to get one, a California certificate of hunter education completion or equivalent with a unique number imprinted on it is required. There are numerous online courses. Hunter-ed.com, for instance, offers courses in 33 states, including California. The class costs $24.50, and you aren’t required to pay until you pass and want to download the certificate required for a license.

However, in surveying the course outline at Hunter-ed and others, while they appear to be well designed, none of them provide information about interacting with other recreational users or their dogs. “There’s a really heavy burden on the hunter to know where people are and to plan accordingly,” Nellis explained, “In the Southern California forests, hunters are out in places where there are a lot of other people, especially where there are trails like Santa Cruz that lead directly out of popular recreation areas. The safety courses ought to include issues relating to those type of areas.”

Dog Owner Responsibilities

Not everyone feels the hunters were the problem, however. “I’m not making a judgment on this particular situation, but it has been my experience that most dog owners believe their animal can do no wrong,” an online Independent reader who goes by the handle “Igj” commented. “The owners know the personality of their animal, strangers don’t. When an owner says his animal ‘would have stopped barking,’ is there some reason that the person that was being barked at should have known that?

“If an owner can’t keep his animal within sight, it’s prudent to keep it on a leash. This is a very unfortunate accident,” Igj continued, “but to make the assumption that this hunter should have known that this large barking dog was ‘harmless’ without having seen it before is not right.”

As it turns out, having off-leash dogs in the forest is completely legal as long as they are outside the recreation area. “There is no leash requirement in general forest areas,” said Andrew Madsen, Los Padres Forest public information officer. “The key concept is that forests are natural open areas, unlike parks which are controlled and have a different purpose.” Ranger Smith echoed that but also noted the importance of dogs being under owner control. “It’s both a health and safety issue,” he explained, “and there should be enough control that they aren’t chasing wildlife.”

Smith uses what he called an “electronic collar” on his own dog. The collar is capable of providing a small shock that can be used as a type of adverse therapy to control behavior. The more expensive ones also can be set to vibrate or beep modes as well. “It only took using the shock button twice when the dog took off after a jack rabbit,” Smith noted. “Now I have it set so that it beeps. Any time I need him to come back to me, I hit the button.”

Use of shock collars are extremely controversial, and a number of animal welfare organizations, among them the Humane Society, warn against their use or actively support a ban on their use or sale. “At best, they are unpleasant for your dog,” the Humane Society says, “and at worst, they may cause your dog to act aggressively and even bite you. Positive training methods should always be your first choice.”

Agency Rules — Lax Enforcement

One of the major issues creating confusion regarding leash laws is the multiplicity of agencies responsible for managing public lands in Santa Barbara County and the relatively lax enforcement of leash laws by most of the agencies. Though dogs may be off leash in a good part of Los Padres Forest, that isn’t the case when it comes to California State Parks, Santa Barbara County Parks, or any of the various city parks. Almost universally, with the exception of specific open space areas such as the Douglas Preserve, private preserves like Elings Park, or a section of the shoreline east of Arroyo Burro Beach, dogs are required to be on a leash no more than six feet long.

However, the problem is that, for the most part, in almost all publicly managed areas with leash laws, they are not enforced. “We just don’t have the park resources to enforce leash laws,” says Jill Zachary, assistant director of Parks & Recreation for the City of Santa Barbara. “We deal with dogs off leash on a complaint-driven basis. When there’s a problem, we deal with it.” Zachary also added that City Parks does encourage dogs to be on leash when in any of their parks, including ones such as Rattlesnake Canyon, which is officially a city-designated wilderness park, and expect dogs to be under control whether on or off leash.

Off-Leash Norm

This lack of enforcement has led most dog owners to assume that it’s okay to have their dogs off leash. Because the Forest Service has maintained front country trails such as Tunnel, Rattlesnake, Cold Springs, San Ysidro, and others for decades, most users assume Los Padres Forest off-leash rules apply on these trails as well as the backcountry areas. But that isn’t true. Almost 70 percent of the front-country trails are actually on City of Santa Barbara land and, as such, are subject to the city’s leash laws.

Many of these trails also cross over multiple jurisdictions, confusing things even further. Jesusita Trail, for instance, begins on Bureau of Reclamation land, then crosses city property, heads through land under county jurisdiction, enters Los Padres Forest, and then crosses back into the city at the other end in Mission Canyon.

Jurisdictional confusion and lack of enforcement have effectively led to a system of public trails on which most of the dogs are off leash and where few of the dog owners have a clear understanding of what the rules are. While this has worked for the most part on the more urban trails, in the case of the backcountry trails — especially those where hunting is allowed — this may not be the case.

Need to Increase Awareness

The trip over San Marcos Pass and down Paradise Road a few miles to the beginning of the Santa Ynez Recreation Area is a short one, less than a half hour from downtown to the edge of wilderness. There is a distinct difference on this side of the mountain. The feeling is much more rural — there’s an actual river that flows through the area and campgrounds and picnic areas abound. The Santa Ynez Recreation Area is host to a hundred thousand or more visitors a year, a great many of them in the spring and summer, but a good number in the winter months as well. You’ll not only find campers but fishermen, mountain bikers heading up to Little Pine Mountain, off-highway vehicle (OHV) enthusiasts, and plenty of hikers. And hunters, too.

Unfortunately, information relating to hunting — either for hunters or the general public — is hard to come by. Not too far into the river canyon there’s a huge sign near the start of the Snyder Trail proclaiming “NO HUNTING WITHIN THE RECREATION AREA” and an additional kiosk with other signs posted on it. It has information about the Adventure Pass, fire danger, cultural resources, and the like but nothing about the “rules of the road” relating to hunting.

Los Prietos Ranger Station, where one might expect to get more information, is just further up the road. While there are maps and other flyers on the kiosk boards outside the office, including a faded notice that bow hunting is illegal inside the recreation area, there is little else to make visitors aware that hunters could pose a danger to them or their dogs if they hike or bike the trails leading out of the recreation area. Nor is their any information on the kiosk at Upper Oso, the trailhead leading to the Santa Cruz Trail where Billy the dog was shot and killed.

“The Santa Barbara Ranger District is basically a day-use area,” District Ranger Pancho Smith said. “Many who come up to the Santa Ynez River do so on the spur of the moment, when they have a few hours for a short hike or bike ride. Often they’ll have their dogs with them and are focused on enjoying a few minutes in the forest not the potential dangers that they might encounter.”

I asked District Ranger Pancho Smith about what he thinks the Forest Service can do to prevent something like a dog being shot from happening again. He sat back and thought about it for a minute. “It’s really tough to figure out what to do about something that appears to be an isolated incident,” he admitted. “I’m not trying to be callous, but there are so many things we’re expected to do and we have so few staff.” He noted that there hasn’t been a recreation officer for the Santa Barbara District for more than a year, and there are no plans to hire one any time soon. Then he paused for another moment and added, “I know people won’t want to hear this, but how much time can I spend on something that almost never is likely to happen again?”

I suggested to him that he may be right, but what if information were provided at the trailheads so that everyone is aware of the potential dangers relating to hunting and be able to prepare better for them? I ran through a number of suggestions that have been passed on to me: Small kiosks at each of the trailheads that lead outside the recreation area where hunting is legal with maps clearly delineating the boundary; signs at the actual boundaries so that hunters, hikers, and mountain bikers know where they are; and perhaps an 8.5” x 11” pamphlet available outside the district office and at the trailheads designed to share information about hunting and what everyone can do to ensure another accident like this doesn’t happen again.

Smith pointed to a chalkboard near his office door. There is a list of four or five things he’s prioritized for action in the near future. “First thing on that list is to work on rewriting the description for the Lower Santa Ynez Recreation boundary so everyone — hunters, hikers, and other users — will know exactly where the boundary is. I’m open to whatever we can do to ensure an accident like this doesn’t happen again,” Smith said. “If there is something we can make work with the limited resources I have available to me, let’s see what we can do.”