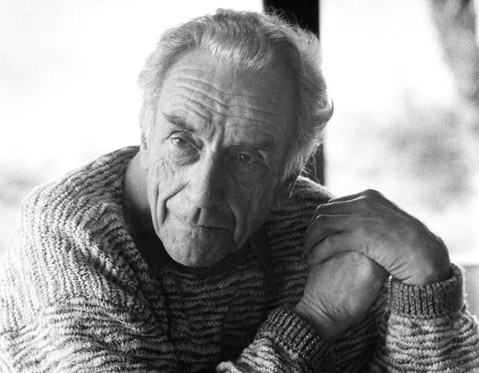

The Fascist grip on Germany was complete after 1934. Leaders of other political parties were jailed or killed; state governments were replaced. It was dangerous to befriend Jews or to associate with those who spoke against the Nazis. George (Jürgen) Wittenstein, studying philosophy, psychology, and medicine at the University of Munich during those dark years, did both. At personal risk and with great loyalty to his friends, he took part in the White Rose resistance, the only German resistance group to publicly condemn the extermination of European Jews. He was one of the few White Rose members to survive and in 1947 published the first report on them: “The Munich Student Movement.”

A longtime Santa Barbara resident, Dr. Wittenstein died on June 14 at age 96. His mother, Elisabeth Vollmoeller, was a successful businesswoman; his father, Oskar Wittenstein, a doctor of chemistry, concert pianist, and aviation pioneer, died six months before George’s birth while testing an airplane. A philosophy of personal responsibility and justice was instilled during Wittenstein’s boyhood by the Vollmoeller family and Schule Schloss Salem, which remains one of the finest schools in Europe. Salem’s revered headmaster, Kurt Hahn, spoke openly against Hitler and fled to England in 1933.

Instead of the ubiquitous swastika, 13-year-old Jürgen’s bicycle flew the flag of the Paneuropean Union, a peaceful unification group banned by Hitler. Compulsory labor and military service preceded his military medic training in Munich, where he befriended Alexander Schmorell, and they shared their hatred of the Nazi regime. His mentor, the art historian Dr. Kurt Badt, was brutalized in 1938’s Kristallnacht attacks on Jewish citizens, and the next day Wittenstein was ordered by the Gestapo, as a German soldier, to stop associating with Jews. More ominously, the Gestapo accused him of homosexuality, a feared Nazi ploy to eliminate enemies.

He began his studies at Munich University in summer 1939, where he met Hellmut Hartert and Hans Scholl. “We had a few magical and exhilarating months,” he said, “free from uniforms, from years of regimentation; free to study, travel, attend concerts, nature; to choose our lodging — wear civilian clothes!”

Warned of his growing Gestapo file, the family made plans for him to leave Germany. In August 1939, after gaining the nearly unobtainable documents, the 20-year-old boarded the Hansa for New York, bringing along a car for his uncle Carl Vollmoeller. A U-turn in the ship’s wake meant they were returning to Germany, and he made a plan to cross the nearest border as quickly as possible. Instead, he drove two stranded and endangered Jewish teens home to Berlin and gave up his last chance to escape Germany. After an intense search by Wittenstein’s wife, the three reunited 70 years later, and Esther and Nat Berkowitz described the terrifying journey, full of flag-downs by police and searches of every car but theirs. They always wondered what kind of high Nazi official or diplomat this elegant and self-assured young man could be who was waved through checkpoints. It turned out their car carried a foreign export license plate and therefore could not be searched.

Back at Munich University, he was redrafted into a medical student company. Constant spying, mail interception, and telephone taps made it dangerous to express opinions and communicate; it wasn’t until after the war that Wittenstein learned that his company commander would mislead the Gestapo if they asked about his soldiers. When their philosophy professor Fritz-Joachim von Rintelen was dismissed, Wittenstein and a friend organized a protest, an unheard-of act in 1941. The first “Leaflet of the White Rose” appeared in spring 1942, denouncing Nazi crimes and appealing to German citizens to defy Hitler’s dictatorship. A call for active resistance followed the friends’ experiences at the Russian front in 1942. Wittenstein took more than 100 photos of the trip, including of the Warsaw Ghetto and the iconic photos that are in nearly all White Rose publications, exhibits, and films of the past 65 years on the subject.

The tragic demise of the White Rose is well-known. Triggered by the arrests of Hans Scholl and his sister Sophie as they distributed the sixth leaflet early in 1943, the Scholls and Christoph Probst were executed, only hours after their trial. Alerted to the trial by a friend, Wittenstein was able to bring the Scholls’ parents to the Palace of Justice, and they saw their children alive one last time. Professor Kurt Huber and Schmorell were executed several months later. Walking past a waiting Gestapo agent to deliver the message, Wittenstein tried to send rescue information to Schmorell via his father, and he smuggled clandestinely collected money to Huber’s destitute family. He was interrogated by the Gestapo in November and by the military court in March 1944, but he disproved their accusations. When later asked why he risked his life repeatedly, Wittenstein, always surprised at the question, would answer “Someone had to do it.”

To be safer from the Gestapo, he volunteered for the front and was posted as a medic to Italy, where he was wounded. He collected weapons from wounded soldiers for Freedom Action Bavaria, a resistance group that saved Munich from Hitler’s order for destruction as the war ended.

It was always with tears in his eyes that he recalled getting his U.S. visa. McCarthyism had made emigrating difficult, as all resistance members were assumed to be communists, but he could no longer live in a country of such horrors. He left Germany with temporary papers for England, but not before marrying Elisabeth Sophie Hartert, though it was two long years until they reunited in the U.S. He also met with students to make plans for a New Germany. In England, he spoke at universities about his disillusioned generation of Germans and about their duty to contribute to the reconstruction of Europe.

Wittenstein continued his surgical training at Harvard and the universities of Rochester and Colorado. Once Elisabeth completed her medical specialization, she became chief of anesthesiology at Denver General Hospital in 1950. George taught at the University of Colorado’s medical school, simultaneously enrolling to get his U.S. medical degree. During their residencies, they were so poor they built their own furniture, a skill George had learned at Salem. He joined the UCLA medical faculty in 1964, serving as professor and chair of the Department of Surgery at UCLA/LAC Olive View Medical Center from 1976-1991, when he retired to private practice. His work as a general, cardiovascular, and thoracic surgeon included returning to Europe to teach and perform the latest complex heart operations in 1956, as well as in China in 1973.

He and Elisabeth had four children, all born in Denver between 1952 and 1955. The family moved to Santa Barbara in 1960, where Wittenstein practiced medicine for 35 years. He loved camping and hiking with them in the backcountry. After Elisabeth’s death in 1966, he married Christel J. Bejenke, MD, an anesthesiologist who helped raise his four young children. He and Bejenke were instrumental in preparing Cottage Hospital to perform cardiac surgery and trained its first “pump-team” in extra-corporeal circulation. He served in various capacities at four Santa Barbara hospitals and UCSB Affiliates. Also a writer and a poet, he was pleased to serve on the boards of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and Friends of the UCSB Library.

His wartime experiences were always painful to recall, and he was haunted by flashbacks and nightmares until the end of his life. For 40 or more years, he did not speak about his experiences. Only when some White Rose relatives were concerned the story was not being told in full, he felt he had to contribute what he knew and give equal voice and respect to all who had done so much and given their lives. He inspired countless students, in classroom visits to schools and colleges, through lectures about the White Rose.

In recognition of his involvement in the resistance, for contributions to German cardiac surgery, and for promoting scientific exchange between the United States and Germany, Wittenstein was awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Federal Republic of Germany and the Bavarian Service Medal, Bavaria’s highest honor.

He is survived by his wife, Christel J. Bejenke; his children Eva Munday, Nemone Wittenstein-Helmling, Andreas Wittenstein, and Catharina Wittenstein-Garrow; nine grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren. In lieu of flowers, a contribution to Planned Parenthood, Domestic Violence Solutions, Sarah House, or a homeless shelter would be appreciated.

To honor George Wittenstein’s life, a memorial will take place at Santa Barbara’s Museum of Natural History on October 11, 3-5 p.m.