Review: The Paintings of Moholy-Nagy: The Shape of Things to Come

Santa Barbara Museum of Art Shines Light on Hungarian Artist’s Postmodern Abstract Paintings

In 1969, when the Bauhaus-trained Hungarian émigré László Moholy-Nagy received his first career retrospective, the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (SBMA) was one of several West Coast stops for a show that many critics considered the most prescient of that tumultuous year. Moholy-Nagy pointed the way toward several of the dominant themes emerging in the art of the 1970s, and he appears to have left a particularly sharp impression on the hard-edge abstractionists and finish fetish artists of Southern California. For Karl Benjamin, Frederick Hammersley, and John McLaughlin, among many others, Moholy’s take on constructivism became a landmark for the lineup.

In The Paintings of Moholy-Nagy: The Shape of Things to Come, the SBMA revisits this fascinating and influential figure with the benefit of another 45 years of cultural perspective and scholarship, and the result is a paradigm shift. Where Moholy-Nagy was once primarily understood as a pioneer in the nascent genres of kinetic sculpture, abstract photography, and light and space art, today his oeuvre looks just as central to another, perhaps more familiar, but no less ambitious form — postmodern abstract painting.

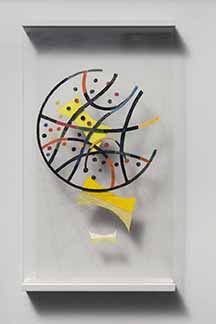

Steering by the light of his own early experiments with emerging technologies, Moholy-Nagy used painting to address the imposing questions raised about fine art by what his contemporary Walter Benjamin called “the age of mechanical reproduction.” Able to imagine such technological developments as television well in advance of their realization, Moholy-Nagy fashioned futuristic worlds in a bewildering array of media. He titled his compositions using combinations of letters and numbers along with terms like “Space Modulator” and “Photogram” that are straight out of science fiction. His appetite for new materials and processes led him to create paintings on laboratory-fresh sheets of Plexiglas and Formica.

Thrown from the wreckage of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of the First World War, Moholy-Nagy landed in Weimar Germany, where he became an influential member of the Bauhaus collective led by Walter Gropius. The clean lines and hard edges of his paintings of the 1920s earned Moholy-Nagy a reputation as a constructivist, and his work was compared to and shown alongside that of the Soviet constructivist master El Lissitzky. In pursuit of the utopian Bauhaus goal of a fully designed world reflecting the unity of all the arts, Moholy-Nagy enlisted the engineers and craftspeople at German lighting manufacturer AEG in 1931 to help him realize what would become the great landmark object of his career, “Light Prop for an Electric Stage.”

The “Light Prop,” which has been re-created in facsimile for this exhibition and is on display in the museum’s Emmons Gallery, is one of those utopian projects that were intended to render all previous artistic media obsolete. A mechanical assemblage of metal, glass, and plastic, it is programmed by a primitive “switchboard” to spin, glow, shimmer, and flash in an unending set of variations intended to engage anyone within its firing range in an immersive aesthetic experience.

At one point, Moholy-Nagy imagined producing “Light Props” as consumer products for people to enjoy in their homes. In practice, the finicky machine tends to break down nearly as often as it works, and the model constructed for this exhibition is true to the original in this feature as well as all the others. When I visited the museum last week, the staff had blocked off the room to see if they could tweak “Light Prop” back into working order again.