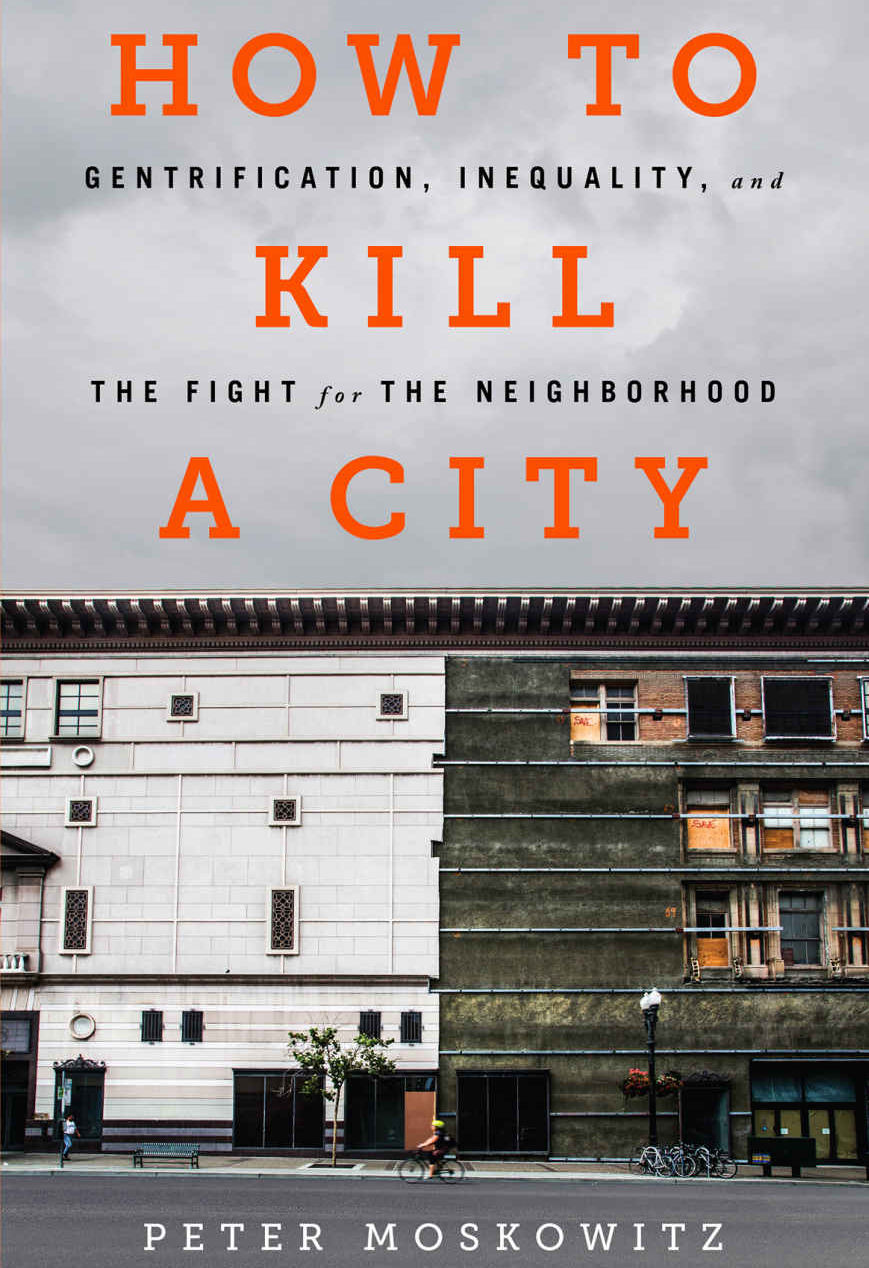

‘How to Kill a City’ Examines Impacts of Gentrification

Peter Moskowitz Writes of Inequality and the Fight for the Neighborhood

Many of us have seen it happen, from the time the first pioneer arrives in a blighted urban area with an idea and some capital and sets to work making the old and dilapidated new and hip, to the day the block boasts an upscale boutique, a trendy café or two, maybe a craft brewery or yoga studio, and the de rigueur gourmet coffeehouse. Eventually, the old neighborhood is completely transformed, decrepit industrial spaces giving way to luxury condos, high-end retail, and a new crop of inhabitants.

In How To Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood, Peter Moskowitz, a New York native who has experienced gentrification firsthand, burrows deep into the forces that drive it and how the transformation of space impacts flesh-and-blood people. There is far more to gentrification than hipsters with money and pluck. Moskowitz wants readers to see how redevelopment produces winners who receive media attention and enthusiastic write-ups in business and lifestyle publications, but also losers who are typically exiled from gentrified spaces and forgotten. What becomes of the losers?

“It’s not a coincidence,” Moskowitz writes, “that cities with disparate economies, demographics, and geographies — Nashville and Miami, Portland and Louisville, Austin and Cleveland, Philadelphia and Los Angeles — are all simultaneously undergoing the same process.” Gentrification is not, Moskowitz argues, about individual acts, though these are often what people notice. Instead, it is “the inevitable result of a political system focused more on the creation and expansion of business opportunity than on the well-being of its citizens.” In other words, the overhaul is about capital, not people or their need for shelter, and decisions about capital are frequently made with little or no regard for social consequences.

Housing policy in the United States is inconsistent, ineffective, and, for more than half a century, riddled with racist practices like redlining. Since the Reagan administration, public housing has also been a perennial target for the budget ax, forcing cities to go it alone. Public housing in New York, New Orleans, and Detroit is synonymous with minorities, poverty, and crime, which is one reason there was such enthusiasm in post-Katrina New Orleans for the demolition of public housing projects. Real estate and business luminaries in New Orleans, along with their allies at all levels of government (allies with the power to bestow tax breaks, subsidies, or zoning relief), seized the opportunity to dislodge the poor and rebuild a swath of the city, something they had dreamed of for decades. Katrina presented the perfect pretext. One result: Roughly 100,000 African-Americans no longer call New Orleans home.

Moskowitz contends that “gentrification almost always takes place on top of someone else’s loss,” whether that is the former renter in San Francisco who, having been priced out of the city, now lives in Richmond or Oakland, or the Detroit resident whose block — which lies just beyond the edge of what is known as the 7.2, Detroit’s heralded locus of investment and renewal — has no working streetlights and sporadic trash collection.

When it comes to housing and urban development, as with other aspects of American life, Moskowitz makes clear that the heft of one’s purse and the color of one’s skin are determinative. How to Kill a City is an indictment of a system that places making a home for capital above making homes for people.