Anthony Doerr Coming Up in Conversations with Pico

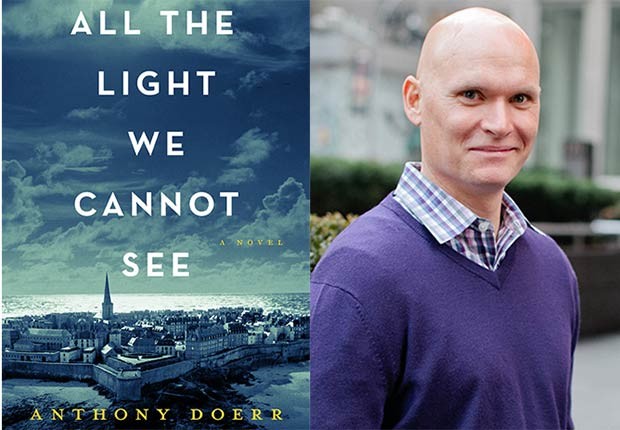

Pulitzer Prize–Winning Author Chats with the Independent Before His Arts & Lectures Event

Anthony Doerr, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of All the Light We Cannot See, will join Pico Iyer for the third installment of the popular Arts & Lectures series, Speaking with Pico, at 7:30 p.m. on May 3 at UCSB’s Campbell Hall. Doerr, whose work has been translated into more than 40 languages, spoke with us recently from his home in Idaho.

What were your early literary influences? When I was seven or eight my mom read us The Chronicles of Narnia. I couldn’t believe that one person created this entire world. As I got older, I went through a Stephen King phase, and then I fell in love with the Beats, Kerouac, even William Burroughs. There was something transgressive about reading Burroughs ― all that drinking and drug use ― while my mom was downstairs fixing dinner.

As a World War II novel, All the Light We Cannot See is unusual in that it centers on two children, Marie-Laure, a French girl, and Werner, a German boy. How did you decide to build the novel around these two characters? Early on all I had was this girl who couldn’t see reading a Braille book over the radio and a boy listening on the other end. I hadn’t placed them in the World War II period at this point. But as I was writing I realized they had to live in a time when radio — one of the most amazing discoveries in human history — was the paramount technology, one that was used in spreading propaganda and organizing resistance.

What was the research like for All the Light We Cannot See? Ongoing. It happened almost all the time I was writing. When I discovered that a natural history museum was central to the story, it led to learning about all different kinds of keys, and the invasion of Paris and what became of all the artwork. Zora Neale Hurston said that research is formalized curiosity. There’s a wonderful serendipity to it.

You wrote a book of short stories called “The Shell Collector” and in All the Light We Cannot See there are numerous references to sea shells. Is there something about shells that fascinates you? Yes, I keep returning to them. I grew up landlocked in Ohio. My mother was a science teacher and every spring break she’d pile my brothers and me into this rusted Suburban and off we’d go to Florida. I was on the beach every day, looking at shells, tiny skeletons, pieces of bone and beauty. The symmetry of shells fascinates me.

Though Werner is very young he grasps the absurdity and futility of war. Did you know that about him from the beginning or did you discover it while writing about him? In almost every case I never quite know characters until I’m writing about them. Writing is an act of empathy, so in the process of imagining characters I’m learning about them. Werner’s a bit like me in the sense that he struggles to do the right thing, like noticing that some of his neighbors were being hauled away and not returning, but he’s also complicit in a way because he’s not willing to protest against what is happening.

After winning the Pulitzer Prize and many other literary awards, do you feel pressured to repeat the success of All the Light We Cannot See? I have this imposter syndrome sometimes. I’m just a Caucasian guy who lives in Idaho and goes to the grocery store and can’t solve the sudoku puzzle in the Saturday paper. I don’t think of myself as some elite intellectual. On the other hand, there’s a feeling of ratification when your work is recognized.