The Fight for State Street

Why Santa Barbara's Main Drag Is Suffering and How to Fix It

To the casual eye, State Street is a sunny, lively avenue of restaurants and shops nestled under red-tile roofs gently sloping toward the Pacific. But look just a little closer at our carefully manicured commercial corridor, and you’ll find real trouble lurking there.

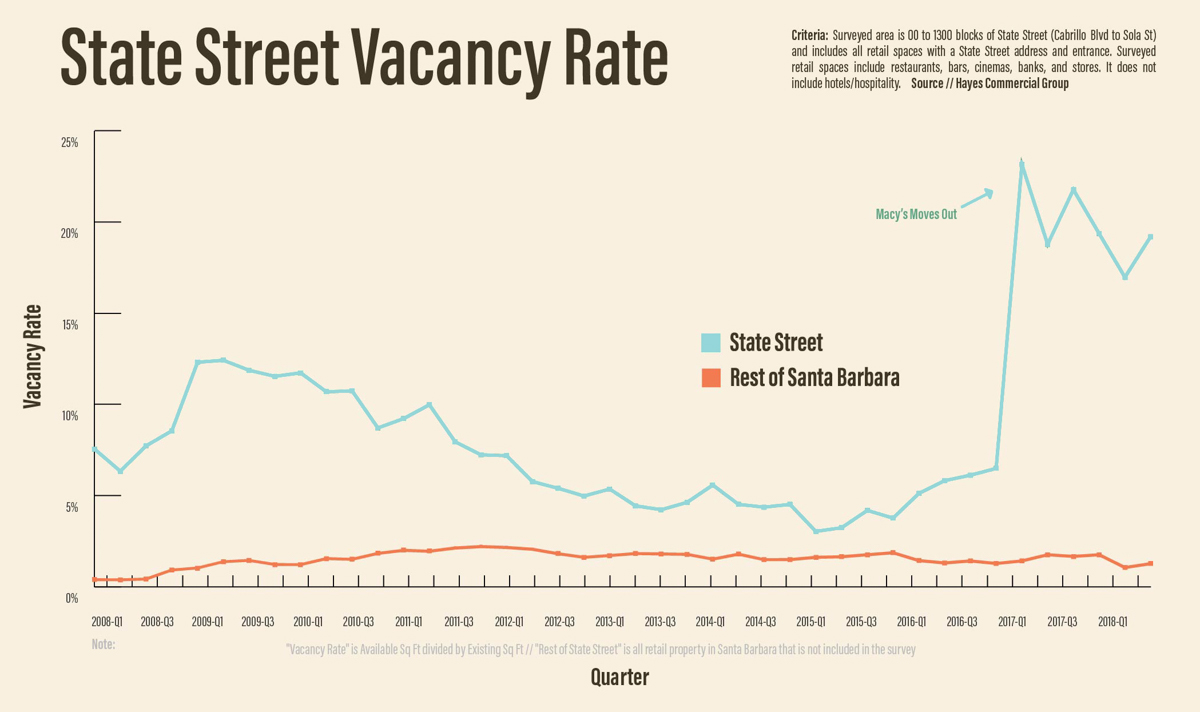

From small family ventures to major retail chains, businesses are folding at an alarming rate. The number of empty State Street storefronts, steadily increasing since 2015, has just reached a record high of 38. Even during the recession, things weren’t this bad.

State Street’s problems are hardly unique. Across the country, brick-and-mortar business districts are feeling the squeeze of e-commerce competition, evolving consumer trends, and the general decline of shopping malls. Downtowns are trying to cope with homeless populations and functional obsolescence, as well as higher overhead from minimum-wage hikes and health-care mandates. But while other communities are adapting to this brave new retail world, Santa Barbara is struggling to keep up. Why?

This report will attempt to answer that question and highlight efforts to save and ultimately reimagine downtown Santa Barbara. It will also draw on the advice from experts in other communities that have successfully revived their main street.

Driving the urgency to solve this dilemma is the understanding that as State Street goes, so does the rest of the city. Sales tax revenues fund schools, parks, and police, among other essential services, and continued bleeding from our primary commercial artery would mean serious financial pain all over. As Plum Goods owner Amy Cooper recently put it: “The fight for State Street is the fight for Santa Barbara.”

Read: Top 10 Tips for Fixing State Street By Matt Kettmann | We asked leaders from thriving downtowns in Boulder, Burlington, San Luis Obispo, and Ventura what Santa Barbara should do. Here’s what they said.

Business Unusual

Michael Martz, a founding partner at Hayes Commercial Group, has watched State Street’s vacancy rate ebb and flow for nearly two decades. “There’s always a fair amount of turnover,” he said. But Martz admitted the recent data, which shows a climbing rate despite an expanding economy and improving consumer confidence, “is cause for concern.”

Back in retail’s go-go days, Martz would get 10 offers on a space as soon as it became available. “Retailers wanted to be in Santa Barbara even if it didn’t make financial sense for them because we’re such a small market,” he explained. “It was a branding move. Santa Barbara has cachet in the world.” All that changed when the economy crashed and companies slowly started closing their vanity stores. So went Borders and Macy’s; shortly after that, Peet’s and Chipotle; and soon to follow, Saks and Staples.

It’s a shame, Martz said, because those downtown vanity stores were the kinds of places that drew a broad range of demographics. They were hubs for all ages and wallet sizes. The types of big chains that replaced them, like Marshalls, “are not nearly as exciting,” he said. “The quality is certainly lacking.”

Martz disputed the popular refrain that Santa Barbara landlords charge exorbitant rents compared to similar coastal communities. “Our rents are commensurate with others,” he said. Indeed, a review of asking prices along State Street (averaging $2-$6 per square foot, depending on the block) shows that they match prices in San Luis Obispo, Ventura, Santa Monica, Pasadena, Malibu, and so on. If rates are set too low, Martz warned, we’ll get more 99-cent stores.

The bigger issue, he explained, is the awkward size of so many State Street spaces. Long, narrow, and typically around 2,000 square feet, they’re two to three times larger than what most small businesses want, and they can’t be easily split in half. A lot of properties also offer second-floor or basement spaces that can’t be leased to different tenants but are useless to street-level retailers.

Some storefronts can stay empty for months or even years because either the landlord is stubborn over terms or they have deep pockets and simply don’t mind money not coming in, Martz said. Others are holding out for a certain type of tenant. And then there are those working hard to fill their spaces by upgrading amenities or taking reduced rates.

Martz confessed he’s a little conflicted over how State Street’s problems are publicized. On one hand, media coverage can kick-start conversations. On the other hand, it can scare away investors. “If you’re from Colorado and thinking about bringing your concept to Santa Barbara, you might scan the headlines and think twice about pulling the trigger,” he said. “It’s important to remember that while we may have our challenges, we have a lot of success stories too ….” A brewery, a seafood restaurant, and a men’s clothing store, all locally owned and operated, are about to open smack in the middle of State Street.

Behind the Curtain

State Street landowners are an eclectic mix of family trusts, wealthy individuals, Los Angeles investment firms, mysterious LLCs, and Santa Barbara foundations: just the kind of consistency you’d expect from a recognizable slice of Central Coast real estate. But as Chamber of Commerce CEO Ken Oplinger pointed out, “We also have more absentee owners than most other places — owners who just don’t care.”

Many of the vacant spaces, Oplinger explained, belong to family trusts and LLCs located outside Santa Barbara. “Nine times out of 10, they’re the problem,” he said. “You get enough of those in a community, and it can really hurt.” According to county tax rolls, 927 State Street, which has been empty since December 2016, is owned by State Street Enterprises LLC out of San Diego. The Chaffee Family Survivor’s Trust in Escondido owns 623 State Street, vacant since December 2017. More than a quarter of the 204 frontage properties recorded on State Street list owners with out-of-town addresses.

To help guide State Street back on course, Gene Deering, senior vice president of Radius Group Commercial Real Estate, suggested property owners take on a more dynamic role. “If owners are proactive on upgrades for their building and provide improvements or free rent to prospective tenants, this will increase the chances of them taking a risk on State Street,” he explained. “If you haven’t upgraded your property in the last 15 years, it’s time to see what you can do.” Deering also encouraged landlords to collaborate with their neighbors on modernization projects. “You have more influence than you think.”

Throughout two dozen private conversations with State Street tenants about their landlords, three names came up often. Jim Knell, founder and chair of SIMA Corporation, was described as particularly difficult to work with, allegedly bargaining in bad faith and squeezing every possible penny out of his tenants. He disputed these accounts. “It’s real easy to make generalizations without facts,” Knell said. “Of course that is the essence of ‘fake news,’ isn’t it?”

Richard Berti was also described as challenging, reportedly charging high rents for outmoded spaces. Berti countered that he’s in fact lowered his rates in response to State Street’s troubles and worked with tenants to keep their stores open. Berti instead blamed the Funk Zone for diverting foot traffic away from State, and he criticized the city for its inaction. “The city has done almost nothing to help, other than to hold meetings,” he said. “The benches are gathering places for vagrants. The sidewalks, streets, and lighting are not well maintained.”

The third name mentioned was often Lynne Tahmisian, owner of the retail and office property La Arcada on the corner of State and Figueroa streets. Tahmisian’s tenants — and those around town who simply know her by reputation — are quick to sing her praises. She blends a sharp business wit with empathy for her fellow Santa Barbarans, they say, and finds ways to make deals to everyone’s benefit. Tahmisian said she inherited her management chops from her late uncle Hugh Petersen, who bought the property in 1972. “His philosophy and mine are to [rent to] local entrepreneurs,” she explained. “I often say it’s difficult to get into La Arcada, but once you do, we will do just about anything to keep you and help you succeed.”

Tahmisian maintains low rents to help La Arcada’s family — “Because that’s really what we are,” she said — and will sometimes waive monthly payments altogether. “Compassion has to start at home,” she said, acknowledging the steep hill State Street must climb. “Yes, I am very concerned about our retail future,” she said. “We have to develop new mindsets that center on our community rather than on ourselves individually.”

The Viejo Look

There is a reason State Street feels preserved — though some would say hung up — in white-stucco time. Since 1960, a quietly powerful group of volunteer architects, historians, and planners has closely guarded the heritage of what’s called El Pueblo Viejo (The Old Town). They designate landmarks and scrutinize new building projects to be sure they keep within the city’s classic Spanish Colonial aesthetic. Any landowner or developer wanting to alter an exterior or build something new in this highly protected area of downtown must win the approval of the nine-member Historic Landmarks Commission (HLC).

The HLC is often credited with keeping Santa Barbara from looking like Newport Beach, but it’s just as frequently derided as unnecessarily difficult and unfairly capricious, as well as a potential impediment to the kinds of development projects needed to breathe new life into the State Street corridor. The Santa Barbara Independent spoke with four applicants in various stages of review with the HLC who discussed their experiences on the condition of anonymity so as not to jeopardize their projects. All four described costly delays in the process and hostile attitudes by certain commission members. There was also a consensus that the HLC, largely composed of retirees, is driven by personal no-growth agendas that are setting up the city for further failure. Said one particularly annoyed applicant: “They’ve got one foot in the grave and another on a banana peel.”

In April, the HLC denied a request by the Montecito Inn — still recovering from Thomas Fire and debris-flow fallout — to install a black awning over its new Franklin’s Crab & Co. restaurant. The commission demanded that the awning be dark green instead. Inn owner Danny Copus appealed the decision with a blistering letter to the City Council. “In all of the city’s good work that it does to keep our town looking beautiful, it is at times notoriously obsessive compulsive,” he wrote. This kind of arbitrary decision-making, he said, is “holding back people from even wanting to do business at all in our fine community because of the occasional absurdity of process to get anything approved.” And that, Copus concluded, “is partly why we have so many vacant storefronts.” The council voted unanimously to grant his appeal.

During the HLC hearing on June 27, chair William La Voie chastised a designer hired by City Hall to develop its “No Smoking” signs. It was a classic example of La Voie’s style, which so many have described as aggressive and condescending. (Originally appointed in 1993, La Voie was temporarily suspended at least once before for similar behavior.) At this particular hearing, after vigorous debate over a specific shade of brown, La Voie jumped in: “Did you look at the sign sections in the EPV [El Pueblo Viejo] guidelines? Did you?” Before she could answer, he continued: “You did not. We have extensive guidelines on what signs are supposed to look like. We can control the font, color, and shape. … We are not Los Angeles. We are Santa Barbara. We are creating old Spain in America.”

Raising his voice over fellow commissioners now chuckling at the one-sided exchange, La Voie went on berating the stunned designer. When she asked to respond, La Voie told her no. City leaders have privately expressed a desire to replace La Voie and other members of the commission, but they say it’s difficult to find younger experts willing to donate their time. Three of the commissioners’ four-year terms, including La Voie’s, end in December 2018.

Time = Money

Follow any State Street business story long enough, and you’ll wind up at 630 Garden Street. That’s the home of the city’s Community Development Department (CDD), where a staff of 75 planners, building inspectors, and safety officers oversee almost every aspect of Santa Barbara assembly, from grand new edifices to retiled bathroom floors. Employees there work particularly hard, and these days even harder, just to keep pace with recent housing initiatives.

Ray Mahboob, who in the last few years has become one of Santa Barbara’s more prolific developers, respects staff as individuals. “They’re all good people,” he said. “Everyone is doing their best.” But the department’s permitting and approval process is nothing short of a slow-moving disaster, he declared. “The whole system is broken. It needs a complete overhaul.”

This sentiment is shared by many other developers, architects, contractors — nearly everyone who brushes against the CDD. Even a few City Hall leaders privately acknowledged the morass of confusion and inefficiency within the department, but they’re loath to spend the political capital or retirement pension it would cost to blow the whistle. “We need to be willing to ask uncomfortable questions,” said one city official who asked to remain anonymous. “The first step is to even admit we have a problem.”

Commercial investor Jason Jaeger of Jaeger Partners agreed with Mahboob. “Every step of approval is excruciating,” he said, explaining that projects in Santa Barbara take three, four, or five times as long to get off the ground as they do in other communities. He talked about how one client — the small AH Juice Organics café on Haley Street — had to wait 18 months to open its doors. Another client — this one on State Street — has been on ice for more than a year and is still counting the days. They’ve spent $1 million more than they’d budgeted to reach this point. “Our permitting process is the kiss of death,” said Jaeger.

In a July 20 letter, an architect vented to city officials his “extreme” disappointment and frustration with the permitting process, explaining his clients had endured seven rounds of plan checks for a minor permit revision. “Each submittal costs us thousands of dollars and weeks of time,” he said. “At this point, we cannot afford to do another.” The problem was not limited to this particular project, he went on. “[It] is substantive enough to significantly dissuade architects and business owners from doing business in this city. … We have worked with many agencies throughout California and have never experienced this level of capricious, unending bureaucracy.”

Store and restaurant operators have also recounted instances where planning staff made errors that cost them tens of thousands of dollars with no avenue for recourse. Other common complaints involve multiple planners interpreting the same building code in different ways, as well as massive projects and minor requests clogging the department’s narrow workflow.

Mahboob told his own story to illustrate the dilemma. Not long ago, one of his new State Street tenants was trying desperately to connect with a city planner for final sign-off. They were never able to reach the proper person, so the tenant demanded that Mahboob include a provision in the lease that stated if the city didn’t respond within 60 days, they could break their contract without penalty. “I’d never seen that before,” said Mahboob. “We’re building a reputation. The tenants all talk.” Beyond these procedural frustrations, Mahboob and others worry the CDD may lack the youthful energy and radical revisioning ability needed to resurrect State Street.

CDD director George Buell defended his department. Though he conceded its permitting process is “rigorous” and at times “extensive” (especially when there’s a difference in design opinion among a project applicant, a review board, or a neighbor), it has also set “a high bar that has played an appropriate role in ensuring new development remains quintessentially ‘Santa Barbara.’ My advice to the project proponent who is frustrated with these things,” he went on, “is to seek advice from planning staff and a local design professional who has a proven track record in achieving timely project approvals.”

Councilmember Randy Rowse stuck up for the CDD as well. “I’ve gone through the permitting process a few times between my house and my business,” he said. “It can seem intimidating and arcane to the uninitiated, [but] if the rules and pathways [are] very clear from the beginning, the process can work.” Rowse suggested perhaps creating a new staff position to act as a facilitator between business enterprises and the planning department. “While I hesitate to pile on more government, the right person might be able to help manage expectations and clarify the path toward completion,” he said.

Developer Neil Dipaola declined to say anything critical about the planning department, but he did emphasize a need for honest assessments of customer experience. “Let’s get some objective data,” he said. “Let’s find out who’s been applying for permits and see how the process went for them, because the first step is understanding the problem. And if there’s no problem, fine, we’ll explore other issues. But let’s get the data first.”

Two years ago, Buell heard a similar suggestion but took it a different direction. Instead of polling planning customers, he surveyed planning staff. He asked them to assess their own abilities and performance. The results showed the department was executing its duties exceedingly well.

The Blame Game

If there is one thing all State Street stakeholders can agree on, it’s that homelessness is a complicated societal ill that’s bad for business. Landlords and storeowners frequently claim that homeless people scare away tourists and keep families from venturing downtown. Maggie Campbell, director of the Downtown Organization until her abrupt departure in January, partially out of exasperation over this very issue, pushed hard for an increased police presence as well as the removal of the sidewalk benches where panhandlers perch. She commissioned a “Retail Strategy” study that supported her efforts by concluding the concentration of loiterers was a “GIGANTIC issue.”

After a homeless man killed a 35-year-old man in front of his wife and 5-year-old daughter as they were having dinner at a restaurant in Ventura this April, Santa Barbara landlords began warning City Hall that a similar tragedy was waiting to happen here. One merchant owning a lower State Street candy store waved an adult toy in front of the City Council to graphically describe how a homeless man accosted one of his customers. Frustration is at a boiling point.

SIMA’s Jim Knell described downtown’s homeless people this week as a “major, major” contributor to vacancies. “Especially when you see these guys who sit around with all their belongings and a pit bull and smoke dope.” The police, Knell said, echoing other landlords, don’t act on complaints strongly enough. “The cops only say, ‘No begging.’ They don’t actually say, ‘Move on.’”

Santa Barbara Police Department spokesperson Anthony Wagner addressed this common criticism of the police. “When you hear an uproar about what the police are or aren’t doing, it often means people just want the problem to go away,” he said. Wagner acknowledged officers often receive calls about disheveled or odorous people lingering outside doorways, but he explained police can only ask them to move away. “It’s not illegal to be unsightly in public,” Wagner explained. “There’s integrity to upholding the law, and part of that is recognizing all human beings have rights.”

In 2015, Santa Barbara’s main tool for patrolling the behavior of people living on the street was stripped of its legal teeth. The Supreme Court ruled that asking for money is protected by the Constitution as free speech. That happened in the same year the City Council had updated its toughened “abusive panhandling” ordinance. “So we’re not going to police our way out of this,” Wagner said.

The department is now focusing on other deterrent strategies, including its Restorative Policing team, which diverts homeless offenders out of jail and into support services. Over the last year, 38 clients, a few of whom were responsible for hundreds of police calls, were successfully shepherded through the program. None has received any new citations, and all have agreed to work for at least six months with a caseworker. “We are very proud of our graduates,” said Sergeant Bryan Jensen. “They are some of our best success stories.” The department is also growing the ranks of its civilian Ambassadors and Volunteers in Policing programs. According to the most recent data, homeless-related crime is at a four-year low.

“On balance, we have to acknowledge that people living on State Street is a problem,” said Eddie Taylor, CEO of United Way Northern Santa Barbara County. “But blaming people for what we consider to be complex economic issues is not the solution.” Jeff Shaffer leads United Way’s Home for Good initiative, which connects homeless people with family members, aid programs, and work opportunities. Next weekend, he’ll host a reunification blitz, hoping to help 15-20 people. Shaffer has been encouraged by a recent shift in tone among business owners who seem less quick to scapegoat people living in transience and more willing to collaborate with social workers. “We advocate for people on the street, but we also advocate for businesses,” he said. “We recognize they’re suffering too. It’s a work in progress, this relationship, but we’re already seeing positive changes.”

Follow the Leader

Right now, State Street is a hot potato of a problem. Everyone’s looking to someone else for the solution. But in the end, said the Chamber’s Ken Oplinger, it’s up to City Hall to lead the charge with relentless buy-in from the rest of community.

The last time State Street was brought back from the brink was almost 30 years ago, when then-mayor Hal Conklin rallied Santa Barbara’s citizens to reenvision downtown. The effort successfully swept away adult bookstores and nighttime crime creeping up the blocks and replaced them with Paseo Nuevo and a bustling arts district. “It’s time to do something like that again,” said Oplinger. “It’s time to push the political leadership to make this a priority.”

Mayor Cathy Murillo and Councilmember Rowse, typically on opposite ends of the political spectrum, have joined forces under the common banner of State Street. “We’re working really well together,” Murillo said. Both cited a design charette hosted by the Santa Barbara chapter of the American Institute of Architects as a sign of positive momentum. Out of it came a rich collection of ideas on how to integrate housing into commercial spaces, which has been almost unanimously endorsed as a critical part of any State Street plan. But for it to be feasible, developers have warned, parking requirements must be significantly reduced.

The architects also brainstormed ways to repurpose Macy’s, the biggest and most daunting black hole in town, including the creation of a graduate business wing from UCSB or Westmont. More recently, rumors have started to swirl that an IMAX movie theater is being considered. AIA Boardmember Barry Winick said his group will host their ArchitecTours 2018 in early October with the theme of rediscovering life, work, and play opportunities downtown. “We’ll focus on projects that show an imaginative use of space,” he said. “SBCAST is a good example.”

Murillo said she’s busy on a whole host of State Street fronts. She’s working with the Downtown Organization on a new window-dressing program, starting conversations with commercial brokers about a potential vacancy tax, and mulling more permanent public art. She’s also in early talks about expanding the Farmers Market to include restaurants, coordinating with Women’s Economic Ventures on a buy-local program, and organizing housing workshops. “The point of the workshops,” she explained, “is to hear from the community: ‘We’re giving you political permission to pursue this.”’ In September, she and the council will also get an update on the Accelerate permit-expediting program.

Murillo credited Assistant City Administrator Nina Johnson for doing a lot of the city’s heavy State Street lifting. “She doesn’t toot her horn enough,” Murillo said. Dispensing with the doom and gloom that tends to dominate discussions about the downtown, Johnson called the high number of vacancies “a huge opportunity to change the retail mix downtown.”

Johnson said it’s incumbent upon the city to minimize the financial gamble for hopeful State Street tenants. “All of us need to focus on lowering the risk environment to help new businesses get started,” she said. To that end, she’s organizing a speed-dating-style event next month that will link entrepreneurs looking for space with property owners and brokers with downtown availabilities. “This model would help us reduce the number of vacancies quickly, bypass the permitting process, and add new shopping excitement to State Street,” Johnson said. “It might even lead to a long-term arrangement.”