The (Un)natural Disaster of California Fires

Severity Will Increase as Society Changes the Global Climate

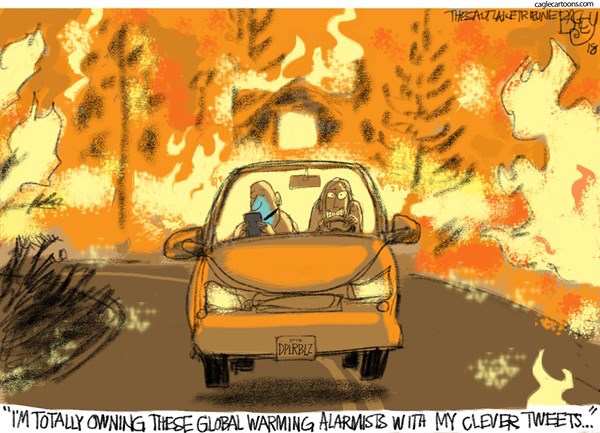

Earlier this month, with hundreds of people missing and over 85 killed by forest fires throughout California, the President of the United States used Twitter to threaten to withhold federal aid. His reasoning almost brushed reality. He was correct that the disasters burning throughout California are rooted in human factors. He is wrong if he thinks he is not complicit.

I thought about his statement as I climbed Montecito Peak the next morning. The journey was sobering. My drive to the trailhead was blocked, the road closed to repair damage from the January disaster which left 21 dead and two still missing. Taking a detour, I passed boulders stacked alongside vacant houses. Eventually I joined the hiking trail, rising into a charred landscape of still-blackened brush. At the peak, I was struck by two views. Below, construction crews rebuilt and repaired houses. South, a pillar of smoke rose near Los Angeles.

This is all new to me. Growing up in the Midwest, I frequently watched green clouds spin into funnels overhead, and a friend lost everything when his town was obliterated by a tornado. But California is different. The scale and frequency of destruction seems unprecedented.

I interrogated friends, colleagues, and experts in Santa Barbara for explanations. The most common reasoning is that California’s current disasters are caused by reckless real estate practices. A co-worker told me fires are natural, but the populations of people living in burn zones are not. There is some truth to this. A recent study in Science found that the burgeoning housing crisis and lucrative real estate market will spur the construction of approximately 645,000 houses in “high severity burn zones” in the next 30 years, meaning that every succeeding burn will take an increased human (and economic) toll. But how “natural” are the fires themselves?

To find out, I contacted Chumash expert Jan Timbrook. While fires have burned in California for millennia, her work clarifies, different methods of managing fires can change the ecology and flammability of the land itself. According to Timbrook, the Chumash used very different fire management techniques. They would frequently start small fires, burning underbrush as part of a sustainable agroforestry cycle. These small fires incidentally kept fuel from accumulating, minimizing the possibility massive fires could erupt.

This management changed when the U.S. government took over. By 1935, the Forest Service had instituted a “10 a.m. policy,” dictating that every fire should be suppressed by the morning after it was reported. Over the course of a century, with this unique view of fire as a foe to be vanquished, the United States shifted the ecology of forest fires. According to Forest Service researcher Mark Finney, this approach facilitates the buildup of flammable plants, turning swaths of the American West into a giant tinderbox. Over the years, the question has shifted from not if, a massive fire would break out, but when.

By most projections, these fires will continue increasing in severity as our society alters the global environment. While many Americans hope that the GOP and fossil-fuel industry possess some hidden scientific knowledge that the rest of the world lacks, outside this bubble it is widely accepted that humans are driving global warming. With atmospheric carbon levels roughly double what they have been in 400,000 years and rising precipitously, it has become impossible to understand any weather event without accounting for the social processes that fill the atmosphere with carbon.

In this context, does global warming cause forest fires? This question is off the mark, according to environmental consultant Joe Romm. Instead, the relationship between natural disasters and global warming is similar to that of a baseball player on steroids. Did the player break homerun records because of steroids? While this is difficult to judge, the player’s performance cannot be understood apart from the drugs enhancing his performance. Similarly, our disasters are indelibly intertwined with global warming, and the social processes causing it.

These issues are not likely to improve. Several months before the Camp Fire was sparked, the Trump administration released a report that admitted that global warming is occurring, yet embraced the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s worst-case-scenario of 7 degrees Fahrenheit of warming. In fact, this administration seems eager to hasten these processes by freezing fuel-efficiency standards, reviving coal, granting tens of billions in fossil-fuel subsidies, and allowing fossil-fuel pundits like the Koch brothers to spend hundreds of millions of dollars shaping legislation, information, and elections.

Standing on Montecito Peak as the fires rage, the drought deepens, and the climate crisis worsens, Trump’s tweet reminded me that people are at the root of the devastation. In this light, I found myself asking: How many lives and homes are the Trump administration and fossil-fuel industry willing to cannibalize before change is enacted? Would they burn the world if it meant they would be kings of the ash?

Jordan Thomas is an environmental anthropologist and Marshall Scholar with graduate degrees from the University of Cambridge and Durham University. He is currently transitioning to Santa Barbara to study forest fires.