Retain Oil Rigs for Sealife

Reenvision Platforms as Habitat for Endangered Ocean Creatures

In 2014, I proposed to the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum that they share Marine Megatropolis, an exhibit inspired by the seven years Andy McMullen and I logged 850 dives documenting marine life, fishery enhancement projects, and research beneath the offshore oil platforms of the Santa Barbara Channel. By 2018, when the show was up, the decommissioning of Platform Holly catapulted my wife, Susanne Chess, and I into the surrounding controversy.

Some of our environmental leaders are recalcitrant in their position that the platforms be completely removed, their foundations blown up from 15 feet below the seafloor’s mudline and dragged away, out of our backyard. In 1997, platforms Hazel, Heidi, Hilda, and Hope were decommissioned. In so doing, 4,000 tons of marine life were sent to rot in a Long Beach landfill. Much of my photographic work, part of a study with Scripps Institution of Oceanography in natural biofouling and the feasibility study that led to California mussel harvesting, had been with Hilda. The deaths of millions of sea creatures broke my heart.

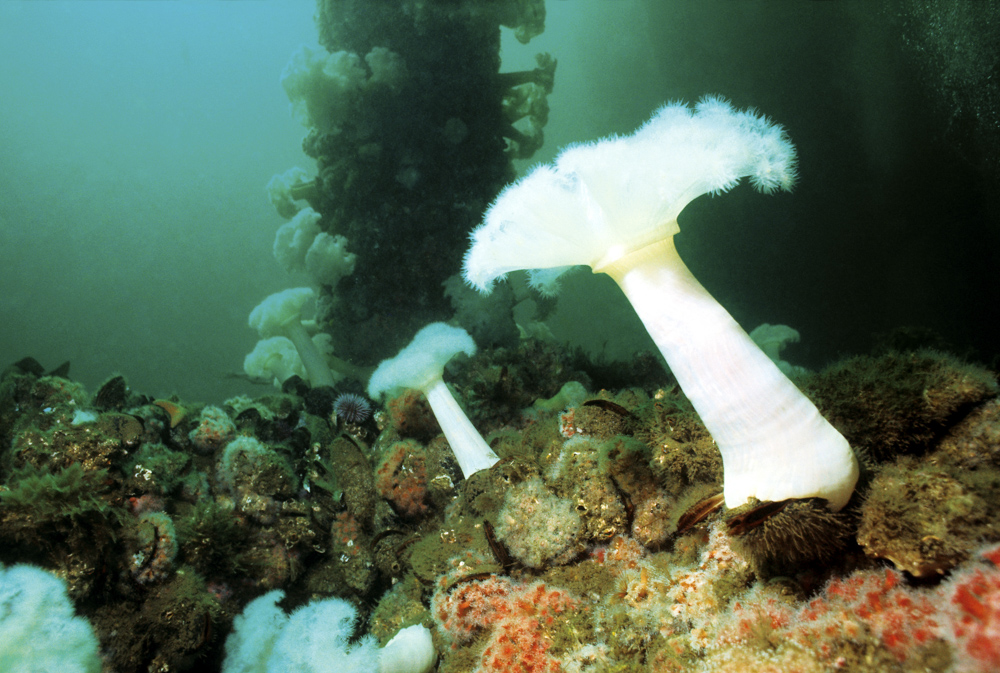

We all know our oceans are in peril; it’s not something we knew when the platforms were towed into place. It is incumbent upon us to protect life wherever it finds sanctuary, even on the legs of offshore oil platforms in the Pacific Ocean. Below Platform Holly is a marine ecosystem 12 times more productive than any reef (see tinyurl.com/platformhabitat). The marine community below, established more than 50 years ago, enhances the Santa Barbara Channel and Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary.

Plug the wells. Remove the rig. But preserve the jacket, the structure life settles on, swims about, and crawls under. Our offshore platforms are hundreds of feet of vertical reef in open water, allowing the current to carry food through continuously.

“Rigs to Reefs” generally involves dumping the jacket in an approved location or cutting off a rig’s marine-life-rich upper 80 feet for navigational safety. Let’s rethink this. Leaving the platform, cleaned of its oil production hardware, preserves the reef and the marine life that depend on it. Bocaccio rockfish, a species of concern in Southern California waters, are plentiful under the rigs.

Reuse the lower decks for staging cage-free fish farming, research, and recreation. Use the infrastructure of cables and pipelines between the vertical reef and the shore to transport energy to and from safe undersea storage of clean saltwater batteries that do not disrupt the ocean or benthic communities. Move water from desalination facilities designed to comply with newly published UN Sustainable Development Goals. Repurpose as an offshore transportation hub. This is where new ideas come in. Collaborative uses can contribute to the hefty maintenance costs.

It is the responsibility of the State of California to decommission Platform Holly. This offers a historic opportunity to reenvision the reef it’s become, to embrace what we see as the social legacy of the environmental movement: “P” for Preserve, Protect; “R” for Recycle, Reuse, Repurpose, Reclaim, Reinvent.

All that stands in the way is reenvisioning our offshore platforms as irreplaceable assets, as launchpads for exploration, for a new offshore economy. For our lawmakers to pave the way with policies necessary to make it happen.

“Marine Megatropolis (1974-1981): Photographs by Bob Evans” exhibits at the Channel Islands Maritime Museum in Oxnard, May 15-August 26. It is the first exhibit to travel from the Santa Barbara Maritime Museum. Evans will give a talk on May 15 and on July 17, both 6:30-8 p.m. See marinemegatropolis.com for more.