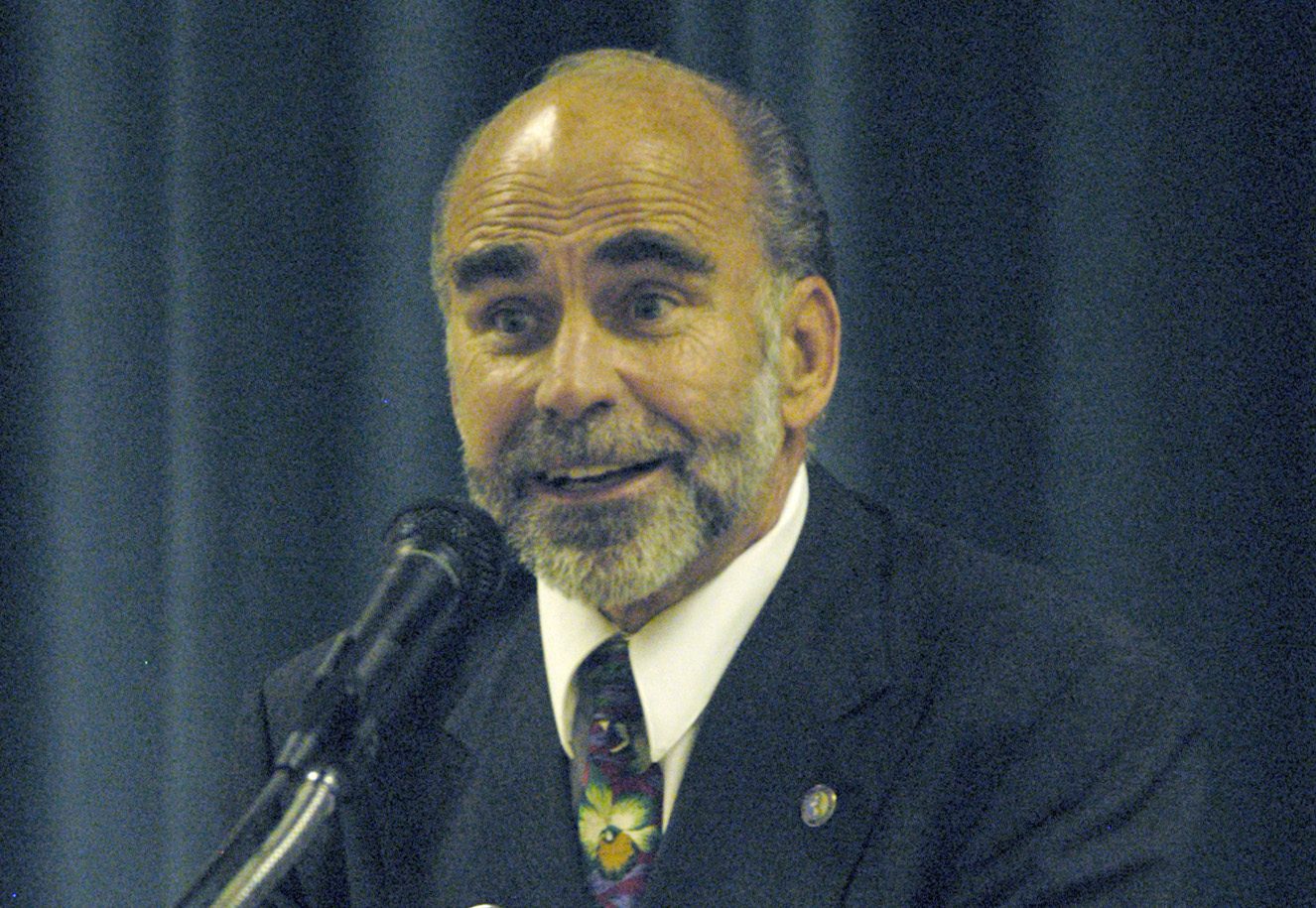

Adios to Bruce Rittenhouse, Seven-Time Santa Barbara City Council Candidate

Out of the Closet and Into the Great Beyond

It took me a while to figure out that Bruce Rittenhouse was not the crypto-fascist megalomaniac I long supposed. First impressions die hard with me. And I had my reasons.

When Bruce exploded upon the Santa Barbara scene in the 1980s, it was as an anti-homeless demagogue and would-be savior of downtown from the unwashed hordes who had, in fact, occupied City Hall for months as a sustained act of political insurrection. Bruce — who ran for a seat on the City Council seven times between 1987 and 2001 — was all glowering indignation and bushy-browed bombast. Back then, he was advocating for a city-wide anti-camping ordinance of questionable constitutionality. Most famously — and ridiculously — he argued City Hall should red-stripe the curbs where panhandling was to be prohibited. As if panhandlers couldn’t move.

Bruce — who died this week in Puerta Vallarta — never pretended his ideas would work, just that he had them. “At least it’s an idea,” he’d shrug. That, in his mind, put him head and shoulders above the competition.

My sense of Bruce changed drastically after I interviewed him in his Westside apartment located above the gas station by Carrillo and San Andres Street. By then, Bruce had emerged as de facto and self-appointed mayor of the Westside, tirelessly harassing city bureaucrats to provide workable and unlocked restrooms in Bohnett Park, where he had built — on his own dime and by his own sweat — a handball court for the neighborhood kids. His apartment was small and cramped. Mostly I remember the large plastic cola bottles stockpiled everywhere. And the endless succession of stray cats who came in through his window, grabbing a bite of kibble and a scratch and a rub from Bruce before heading out on their appointed rounds. For me, it was an epiphany. Sugar. Caffeine. Stray cats. That was Bruce.

Bruce grew up in Dearborn, Michigan, reportedly the son of Henry Ford’s personal plumber. He served a hitch in the military and worked three years as a cop in Dearborn, but for most of his professional life, Bruce worked as a house dick for the global insurance empire. When he first arrived in Santa Barbara, he was all crisp suits. Eventually, he was subverted by Santa Barbara’s shorts-and-sandals culture. Politically, he remained an indefatigable civil libertarian contrarian. Not content to speak truth to power, Bruce kicked its ankles. When city cops got aggressive in their gang sweeps, Bruce accused them of ethnic profiling. He mocked the gang hysteria sweeping the city. Everyone belonged to some sort of gang, even those, he sneered, “who trotted off to Sunday Mass.”

He met with the police chief, demanding the police remove security cameras from Bohnett Park. When the chief said he would not be spoken to “that way in his own house,” Bruce countered the police station was “the people’s house.” In the heat of political battle, Bruce had two speeds: gleefully savage and savagely gleeful. It was hard to tell one from the other.

Bruce knew something about being on the outside looking in. It was well-known that he was gay. He lived with his partner, Mark, who had contracted AIDS. But no one ever mentioned any of this. It was not to be discussed. Certainly Bruce didn’t. Santa Barbara was a don’t-ask-don’t-tell town; the universe was too. Some things were just not mentioned.

[Bruce Rittenhouse’s longtime partner Mark Champion, it turns out, is not dead, as was originally reported. He is in fact alive and well in Sacramento, having left Santa Barbara abruptly in 1998. “It’s not nice to read you’re dead,” Champion said during a recent phone call, alerting the Independent of this mistake. “It was hard enough processing the news about Bruce, and then I heard it was me, too, who died. I said, you know, ‘What?'”]

Over the years, Bruce grew close with another famously closeted gay political personality, the late, great Santa Barbara mayor Harriet Miller. After one candidates’ debate, Miller reportedly asked Bruce if he liked to drink. The rest was history. Over time, he became her chauffeur and confidant. He took care of her plants and pets when she was away. When Miller’s life partner, Elizabeth, was dying of cancer, Bruce made sure Harriet had all the words to “You Are My Sunshine,” so she could sing it to her one last time. Where Harriet exuded all the gruff, tough authority of a get-stuff-done, middle-of-the-road Democrat who broached no nonsense, Bruce functioned as her court jester. He’d say things she couldn’t say and attack people she had to pretend to like.

In turn, she’d look out for him. For a while, Bruce conducted a political graffiti campaign throughout the Westside, painting in seemingly random public locations — like gas station parking lots — horizontal bars stacked on top of one another in the colors of the American and Mexican flags. He did just enough to generate pointed questions. Complaints were filed with the proper department heads. Miller would quietly intervene, and somehow these messages developed a habit of disappearing.

Today, an openly gay presidential candidate, South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, is running for the Democratic Party nomination. It’s a historic first. It’s a big deal. Weirdly, it just doesn’t seem that way, even as Buttigieg defends his sexual identity in much the way John F. Kennedy famously defended his Catholicism nearly 60 years ago. Times have changed. We’ve all moved on. So too has Bruce Rittenhouse, now largely forgotten, who made Santa Barbara infinitely more noisy, fun, and soulful for being here.