San Antonio Mental Health Guru Speaks in Santa Barbara

Leon Evans Explains How to Turn Futile Efforts into a Success

Of course, Leon Evans wrestled a bear before. Not just once, but twice. The first time, Evans — now in his seventies — took on a 1,200-pound Kodiak from Alaska and got swatted clear across the stage at the Houston Astrodome. That was about 1973. Ten years later, Evans — then in his forties and the senior mental-health administrator in Houston — went up against a 500-pound black bear named Ginger. This time, Evans — an accomplished college wrestler — managed to take the bear down but never managed to pin her, thus losing out on the $10,000 prize money. Both bears, he explained during a recent interview, were muzzled and declawed. “I only look stupid,” he said.

Not even hardly.

Evans has since emerged as a semi-mythological character in the field of mental-health-care administration. He is frequently credited for the screaming success enjoyed by Bexar County (pronounced “bear,” by the way) for its Restoration Center, a sprawling one-stop-shop mental-health and homeless-services program that’s managed to divert 60,000 people into treatment who would otherwise have wound up in jail.

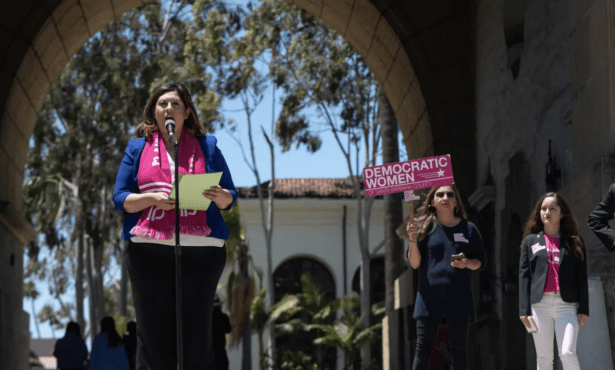

Santa Barbara’s Sheriff Bill Brown — who was appointed by then-governor Jerry Brown to serve on a statewide panel of experts on the subject of mental-health services — describes San Antonio’s mental-health system as “the gold standard.” Brown brought Evans to Santa Barbara to preach the gospel of collaboration and diversion to a choir of highly interested stakeholders participating in Santa Barbara County’s Stepping Up program, which Brown chairs. Attending were a smattering of law enforcement officers, court officials, high-octane county administrators, mental-health providers, prosecutors, and many mental-health advocates. A Texas yarn spinner, Evans knows how to tell stories. “We were a 17-year overnight success,” he cautioned. Collaboration, he stressed, was absolutely key, though it is “an unnatural act by un-consenting partners.” But behind Evan’s practiced patter — his words may twinkle, but his eyes don’t — lie some seriously hard-to-come by accomplishments.

The Restoration Center started off in 2008 with a crisis care center — 16 beds — for the most seriously mentally ill people in San Antonio. Eventually it picked up a detox unit — 28 beds of medically supervised care — that offered 120 days’ worth of supportive inpatient treatment, including an opioid addiction center. Initially, law enforcement figured about 16 percent of the people behind bars had some form of serious mental illness; they quickly figured out the real number is closer to 40 percent. None of this was cheap or easy.

It began when a Bexar County judge invited hospital administrators, medical staff, law enforcement, and mental-health workers to get together. Backing the effort was a retired executive from Valero oil, who had the money and political connections to match his commitment. The judge ordered Evans — then the senior mental-health-care administrator in the county — to make everyone work together. “We discovered we actually liked each other,” Evans said. More important was the fact that everyone was spending millions to treat or incarcerate a relatively small minority of mentally ill patients. The hospitals alone, Evans said, were hemorrhaging more than $1 billion a year because of 2,000 repeat patients, who choked up their emergency rooms on their way back to the streets and to jail. Mentally ill inmates tend to get arrested more, stay longer, and require more expensive custody services. Armed with rigorously collected data, the parties involved discovered that treatment worked. It saved lives and it saved money.

Evans’s arrival in Santa Barbara coincides with many smaller but significant mental initiatives bubbling to the surface simultaneously. The county just got a $6 million state grant to help pay for a new sobering center, 20 beds of step-down mental-health housing, and funding to sustain a second co-response unit, made up of a mental-health crisis worker and a county sheriff’s deputy. The first such unit — part of the Sheriff’s Behavioral Sciences Unit — has enjoyed some high-profile interventions in situations that otherwise could have turned violent. The county just committed another $3 million of state funds to create a new eight- to 15-bed mental-health treatment facility for patients who might have wound up as inmates instead. Even with more programs and better collaboration, the county struggles to find enough places with the right treatment for people with chronic mental illnesses.

Evans shared not only his inspiring success story but also some keen-eyed advice. Data, he said repeatedly, is key to funding, performance, and outcomes. Santa Barbara’s data collection system, he said gently, is archaic and needs an expensive upgrade. “And you need to be operating more as one system, not so many individual systems.”

Mostly, he stressed, “You guys are so close. You’re almost there.”

Of course, Leon Evans wrestled bears.

You must be logged in to post a comment.