Putting Traumatized Cops at Ease

Family of Dead Officer Donates $100K for Free PTSD Therapy

David Anduri was a cop for the City of Santa Barbara for 13 years. Like a lot of cops, Anduri never talked about things. Or at least that’s what his mother, Patti Anduri, said. That silence may well have killed him. Anduri died in October 2014 of liver failure. At only 37 years of age, he had managed to drink himself to death.

Not long afterward, Patti Anduri and her husband, David Anduri Sr., sued City Hall and former police chief Cam Sanchez. Their son, they argued, sustained post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of harrowing on-the-job service calls to which he’d responded. Anduri was pushed to drink, they claimed, because City Hall had effectively prevented him from securing the benefits to which he should have been entitled. Their attorney, Jonathan Miller, filed legal papers in federal court alleging City Hall had violated Anduri’s civil rights. It was, Miller conceded, an untested legal theory. That theory would never get put to the ultimate test. Last year, City Hall settled with the Anduris, agreeing to pay a modest $200,000 to make the case go away.

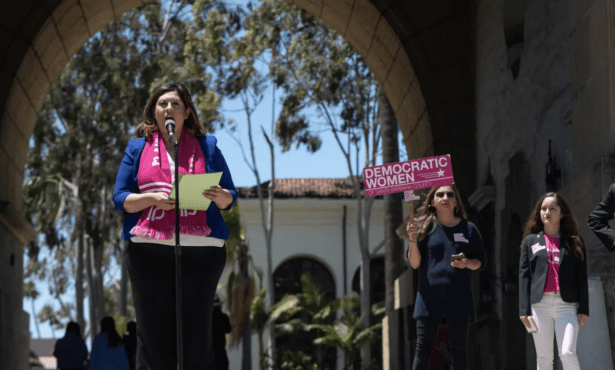

This Monday, Patti and David Anduri returned the favor. At a press conference in front of police headquarters, they presented the Santa Barbara Police Foundation a Prize Patrol–sized check for $100,000 to help sustain a groundbreaking mental-health counseling program for cops, firefighters, and other first responders.

The program, known as At Ease, was started five years ago by retired police sergeant Mike McGrew so that cops, their spouses, and their immediate families could get mental-health treatment, no questions asked and free of charge. That formula appears to be working. This year, 600 first responders have availed themselves of the eight therapists in the tri-county region that the Police Foundation and At Ease have vetted for trauma counseling.

“Five years ago, that number would have been zero,” McGrew said. Typically, after a major disaster, public service agencies might lose up to 10 percent of their employees, McGrew said. After the debris flow, he said that number at the Montecito Fire Department was zero. McGrew attributed that to the PTSD therapy made available.

McGrew worked 33 years for the police department. When he started, the department was dominated by Vietnam-era vets. Feelings were not discussed. “Their attitude was, ‘Suck it up; you’re getting a paycheck,’” McGrew recalled. As leader of the Police Officers Association, McGrew was charismatic, media savvy, and not one to shy away from a fight with city administrators or anyone else. As big and tough as he was, the job took its toll. “After you retire, things have a way of catching up with you. I’ve had 30 years of weird stuff happen.”

In recent years, McGrew has famously found Jesus, become a street preacher, and written a book about his life. And he’s pushed At Ease. Earlier this fall, a benefit event hosted by Pat Nesbitt, the ever-embattled polo-playing hotel tycoon, netted the program $350,000. That — and the Anduris’ $100,000 — will pay for a lot of therapy. McGrew said each session costs $120. But far more critical to the program’s success is the no-questions-asked anonymity of it.

“Your boss doesn’t need to know. Nobody has to clear it. Nobody’s wondering whether something’s wrong with you,” McGrew said.

In the past, cops complaining of PTSD would typically be shunted into the city’s workers’ comp program, a bureaucratic nightmare in and of itself. Either that, or they might be eligible to three sessions, McGrew said, but only after subjecting themselves to the prying eyes of departmental administrators. By pursuing either process, McGrew cautioned, officers knew their fitness to serve might be open to question. Who in their right mind, he asked, would willingly place their careers at risk?

With At Ease, the names of first responders are kept strictly confidential. If that poses a problem for Santa Barbara’s current chief, Lori Luhnow, it’s clearly not a big one. Luhnow was on hand at the Monday press conference, where she spoke glowingly of the program and thanked the Anduris profusely.

“The no-questions-asked aspect is what makes the program so effective and so essential,” Luhnow said. Luhnow cited recent stats indicating that 10 New York City cops killed themselves in the past year. Cops reportedly kill themselves at five times the average rate. Cops also have notoriously high divorce rates.

Luhnow is happy to accept the benefits of the At Ease program, but she’s also trying to change cop culture as it’s practiced in Santa Barbara.

“A lot of us don’t like to ask for help,” she noted.

In response, Luhnow has tried to take the “ask” out of the equation. Officers are now automatically debriefed if they’ve been involved in a potentially traumatic event. No asking is involved. Under Luhnow’s watch, a new peer counseling program has also been initiated. And written into the job description of one sergeant is the oversight of officer wellness.

Patti Anduri said she remembers how surprised she and her husband were when David first joined the Marine reserves and then became a cop. He was, she said, “a naive kid” from Irvine, where he played golf and water polo at the high school where she taught. Anduri’s father was a banker. Their son, she said, was adamant he didn’t want a desk job. Anduri’s first and only cop job was with the Santa Barbara Police Department. There, he saw all kinds of things he couldn’t un-see. He performed mouth to mouth on a man who’d shot himself in the head but managed to live. Blood gushed everywhere. In another instance, he had to deal with a man who’d stabbed himself in the chest and, again, lived. He found his best friend on the force facedown on the pavement, the victim of a work-related traffic accident.

Anduri never talked about any of that with his mom. Not even, she said, when his hands shook so badly he could barely take money out of the ATM machine. Or when he developed a sudden aversion to being in crowds. And certainly not anything about the drinking. Only when he’d been hospitalized for liver failure — and it was clear he was never getting out — did Patti Anduri begin to hear any details. Anduri’s buddies on the force would show up and tell stories. Some his mother found funny, even hilarious. Others, she said were so awful, she’d never repeat them.

“It would give you nightmares if I did,” she said.

Only then did Patti Anduri learn how hard it had been for her son to get treatment and then only from other officers. They encouraged her and her husband to sue. So they did. It was never about the money, she said. From the beginning, the Anduris made it clear they intended to donate any proceeds from the case. That, in part, influenced City Hall’s decision to settle.

“Back then, officers were expected to just bite the bullet,” Patti said. “David just kept it all inside. That’s why At Ease is so important. It allows people to talk about things they wouldn’t share with their family.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.