Creating Hope

with the Dalai Lama

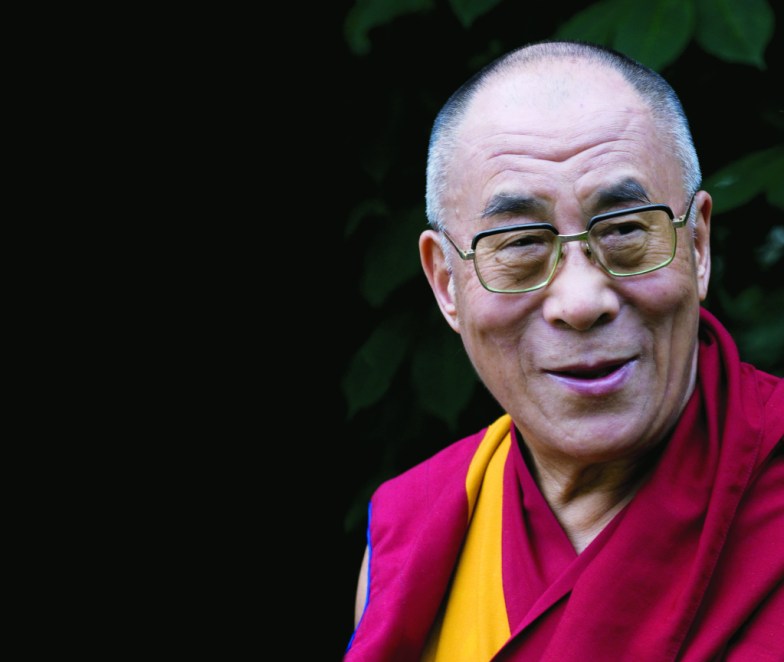

His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama Shares Wisdom through UCSB Arts & Lectures

By Charles Donelan | May 13, 2021

Along with the rush to return to the lives we led prior to the pandemic comes an underlying confusion and fear. While we all yearn to replenish our exhausted supplies of the warmth of human contact through the familiar old repertoire of handshakes and hugs, a bigger potential loss lurks beneath the surface. In the face of so much division in our society, one wonders about the status of the shared assumptions that such habitual greetings represent. As people emerge blinking from this radical social hiatus, will the mutual trust our gestures are understood to signal remain intact? In order to restore the collective emotional foundation on which our habits rest and regain the fullness of connection we crave, we are going to need lots of the world’s most universal value: hope.

The Bodhisattva of Compassion

When it comes to thinking clearly and acting productively in the service of creating hope, one figure occupies a singular place in global consciousness. At age 85, His Holiness, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama has served his nation and humanity for a long lifetime in selfless devotion to the cause of inspiring humans to embrace their innate potential.

To his followers, he is the living manifestation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion, the patron saint of Tibet, and the reincarnation of the 13th Dalai Lama. To the world at large, he commands the kind of respect associated with only a handful of giants who have changed the course of history, people like Mahatma Gandhi and the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. In addition to wielding influence as a political and religious leader, the Dalai Lama occupies an exalted position among the scholars with whom he meets on a regular basis to discuss the latest developments in physics, psychology, and neuroscience.

Equally at home among renowned scientists and his fellow Buddhist monks, the Dalai Lama is perhaps best loved for his exceptional fluency in the everyday language of ordinary people. Steeped in an esoteric tradition with few rivals for complexity, he nevertheless conveys his wisdom with a calm directness and lively humor that has made him among the most popular public figures of our time. When he appears on Tuesday, May 18, as the keynote speaker for UCSB Arts & Lectures’ new programming initiative “Creating Hope,” that’s the voice that you will hear: one attuned to the needs of the broadest possible audience.

It’s a commonplace that so-called natural disasters tend to reveal underlying flaws in society. What’s less frequently acknowledged is the degree to which shifting conditions can uncover untapped strengths. As the leading provider of live cultural events in our region, UCSB Arts & Lectures has a long record of tapping the best talent the world has to offer, regardless of genre, medium, or place of origin. With its emphasis on bringing people together in person, one could reasonably expect that the organization might reduce its programming or even shut down altogether in a time when large gatherings are prohibited as a matter of public safety.

Yet nearly the opposite has proved to be true. Without access to Campbell Hall, the Arlington Theatre, and the Granada Theatre, to name a few of the wonderful venues in which Arts & Lectures ordinarily operates, the organization has nevertheless found multiple ways to continue bringing its message of 21st-century enlightenment to a broad audience.

The Race to Justice series, which featured a galaxy of stars from Bryan Stevenson to Isabel Wilkerson and Wynton Marsalis, initiated an essential conversation that changed the way we think about equality. These events will continue in some form indefinitely as more people discover the powerful network of scholars and activists who are at work redefining American identity from perspectives of knowledge, wisdom, and lived experience. The online House Calls series has reached a global audience while nurturing existing relationships between the Santa Barbara community and the world’s top writers and performers. Rather than disrupting the Arts & Lectures project, the challenges of quarantine have sharpened its focus and renewed its mission.

On Tuesday, May 18, when A&L presents His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama in conversation with Pico Iyer, the program will be available for free to anyone with access to the internet. Iyer, a formidable figure in his own right, is a longtime friend of His Holiness and an adept lay exponent of the Dalai Lama’s Tibetan Buddhist philosophy. The Dalai Lama has long had a special connection to UCSB, the first university in America to establish a chair in his name for the teaching of Tibetan Studies. Professor José Cabezón, the current holder of that position, is both a trained scientist with a degree from Cal Tech and a former Buddhist monk who spent 10 years in a monastery in India.

Over the past few weeks, I have had the pleasure of conversing with Professor Cabezón and Pico Iyer about the upcoming event and about the extraordinary impact the Dalai Lama has had on his constituents and on world history. As the deadline for the story approached, an unexpected blessing took this research process to a higher level. The Dalai Lama found time to send written responses to a series of email questions that Iyer had submitted to him on behalf of the Independent. What follows are some of the highlights of my conversations along with the entire text of our exclusive email interview.

Lives in the Balance

In addition to advising graduate students and advanced undergraduates in the Religious Studies department, José Cabezón teaches one of UCSB’s most popular lecture courses, “The Religions of Tibet.” Speaking with him, it’s easy to understand why so many students, most of whom will never visit this remote place or continue to study Buddhism, are nevertheless attracted to this seemingly esoteric subject. Listening to Professor Cabezón, one begins to get an idea of both the constant threat posed to Tibetan Buddhism by the Chinese occupation of Tibet, and of the strength and resolve of the Dalai Lama as the leader of a nation in exile.

Cabezón’s most recent book, co-authored with Penpa Dorjee, gives a comprehensive history of the Sera Monastery, where he was a monk for 10 years, and which was founded in the 15th century. This ancient institution is now located in India, as are virtually all the principle centers of Tibetan Buddhism. This displacement makes the scholarly work being done at sites such as UCSB all the more important.

Cabezón becomes animated when describing the way that the “religion is dying in Tibet due to restrictions put on monks and lay practitioners” by the Chinese authorities. This is happening despite a “huge growth of interest in Tibetan Buddhism on the part of Han Chinese.” Cabezón said that there have been as many as 10,000 people studying at Larung Gar, a Tibetan Buddhist community that lies within the Chinese prefecture of Sichuan, and that in recent years, the government has sought to reduce their population by bulldozing their homes.

For Cabezón and other Tibetan Buddhists, the threat posed by Chinese interference extends beyond these brutal measures taken on the ground to the very institution of the Dalai Lama itself. China has made its intention clear in regard to the succession of the role. When the time comes for a 15th Dalai Lama to be chosen, China will pick its own candidate, regardless of the fact that, as an avowedly atheist state, it considers the religion of Tibet to be a species of superstition.

The shadow cast by this intention sets off the heroism of the 14th Dalai Lama all the more. For Cabezón, the Dalai Lama’s tremendous optimism about the goodness of human beings is nothing short of amazing. “He doesn’t see the possibility of realizing these ideals as some kind of pie in the sky,” he told me. The Dalai Lama believes that we can change, and despite all that has happened between the two countries, he prays every day for the welfare of China and the lives of the Chinese people.

A Lifelong Friendship

Pico Iyer deserves to be recognized as a key personal and professional liaison between the Dalai Lama and multiple worlds. The two have known one another for four decades and traveled the globe together, including 10 trips to Japan, where Iyer lives most of the year and where the Dalai Lama receives an extraordinary amount of attention and respect.

As the only Buddhist nation willing to stand up to China in order to host the Dalai Lama’s visits — South Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Myanmar have all declined to do so — Japan serves as an important outpost of Tibetan Buddhist worship, with followers traveling from all over Asia to participate in these public events. For Iyer, whose father was also a friend to the 14th Dalai Lama as early as 1960, the opportunity to spend so much time with the man has clearly been a transformative experience.

When I spoke with Iyer by Zoom from his home in Japan, he articulated the logic behind this event with great clarity. In response to the idea of creating hope, he said of the Dalai Lama, “That’s what he’s really done his whole life. He takes very difficult circumstances and finds the hidden pearl of possibility within them.”

Citing the Dalai Lama’s loss of nine of his siblings when he was very young, the task of leading a population of six million people in exile for 50 years, and the burden of carrying out that duty while being opposed by the largest nation on earth, Iyer said that of all the people he’s ever met, “The Dalai Lama has probably suffered the most.” Yet his response to these challenges, according to Iyer, includes what people remember about him most: “his robust confidence, his constant laugh, and his infectious smile.”

He sees the exile of his kingdom to India as an opportunity rather than as a loss. In the wake of recent events, including but not limited to the COVID pandemic, he has a great deal of wisdom to offer because, as Iyer said, “What we’re trying to do is see what good can come out of a seemingly bad event,” and “the Dalai Lama is the past master of that.”

Unlike religious leaders motivated by an evangelical impulse, the Dalai Lama does not seek to convert people. Instead, he sees his mission as spreading a doctrine of secular ethics designed to inculcate universal values of compassion, forgiveness, tolerance, contentment, and self-discipline. Despite a lifetime of rigorous scholarship and a long fascination with difficult concepts in philosophy, psychology, and the sciences, the Dalai Lama speaks plainly and seeks to assist his listeners in becoming more fully themselves, rather than acolytes of him.

When I asked Iyer if the Dalai Lama had changed over the 40-plus years that they have known each other, he said that his fundamental principles remain essentially the same. The methods he uses to communicate them, however, have been modified by the Buddhist concept of “skillful means,” which calls for rhetorical strategies appropriate to the audience at hand.

Iyer also sees this shift as a response to his travels and to the responsibilities he began to shoulder at a young age as the political leader of his people. He is the first Dalai Lama to travel outside of Asia for significant periods of time, and his cosmopolitan experience has had a profound impact not only on his own life, but on the world at large.

For Celesta Billeci, the Miller McCune Executive Director of UCSB Arts & Lectures, this event embodies everything she has sought in establishing this series on the theme of creating hope. “It’s a big honor for Arts & Lectures to be hosting this event,” she told me. “It’s going to be streamed worldwide in 14 languages, and when Pico first proposed it to His Holiness, he responded ‘yes’ within 24 hours.” This willingness on the part of the Dalai Lama to share his thoughts at this time is itself an example of what he will be talking about, which is creating hope.

Direct from the Dalai Lama

The following email dialogue was provided to the Santa Barbara Independent as an exclusive feature in advance of his appearance through UCSB Arts & Lectures on Tuesday, May 18. We present the exchange in its entirety.

What are the most important things those in the West often misunderstand, or don’t know, about Tibet and its culture? In general, prior to 1959, primarily on account of Tibet’s ill-advised determination to isolate itself from the rest of the world, the international community did not have a deep understanding either of our country or our culture. Tibetan Buddhism, for example, was referred to in a derogatory way as Lamaism.

Today, there is an increasing recognition that the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, which adopts the approach of the ancient University of Nalanda in India, extensively promotes the use of reasoning and logic. Currently, a number of scientists are showing interest in aspects of Tibetan Buddhism that correspond to their understanding of the nature and workings of mind and what today is known as neuroscience.

The University of California Santa Barbara is very proud to be home to the 14th Dalai Lama Chair of Tibetan Studies, occupied for 20 years now by Professor José Cabezón. Beyond studying Tibet’s language, its history, and its religion, how can those of us in the West best help sustain both Tibet and Tibetan culture? Nalanda University was a place brimming with intellectual energy. Representatives of a wide range of Indian schools of thought studied there, and through their exchange of ideas enriched each other’s understanding. It was an academic system founded on logic and reason.

Evidence of these processes is reflected in the treatises that have come down to us and which continue to be studied in our monastic centres of learning today. Nagarjuna, for example, elucidated what the Buddha had to say about the correct view of reality. Aryadeva, Bhāvaviveka, Buddhapālita and Chandrakirti in due course built on each other’s work and shed further light on what Nagarjuna revealed.

This system was also sustained in Tibet. Someone like Tsongkhapa, in his youth, travelled to different centres of learning and made himself familiar with the various views being taught. Later in life, when he was preparing to compose his own appraisal of the Madhyamaka school of thought, he first read all the existing Indian commentaries to it and considered the views they contained.

Comparing and exchanging ideas makes a powerful contribution to furthering human understanding. In the present day, this is something we’ve recognised in the fruitful discussions we’ve held with contemporary thinkers and modern scientists.

I know that education is one of Your Holiness’s principal concerns. How can we better train the leaders of tomorrow? It seems to me that modern education by and large fails to foster inner values. Once children enter the education system, there’s not much talk about human values. They become oriented towards material goals, while their natural good qualities lie dormant. Education should help us use our intelligence to good effect, which means applying reason. Then we can distinguish what’s in our short- and long-term interest. Used properly, our intelligence can help us be realistic.

Many of the problems we face in the world today are of our own making. We are afflicted by anger, fear, jealousy, and suspicion. Our modern education has little to offer in terms of achieving peace of mind. Although ways to tackle our destructive emotions are laid out in Buddhist texts, there is no reason why that knowledge can’t be applied in an objective, non-religious way.

Such methods for tackling our destructive emotions are very relevant today. They don’t involve temples, rituals, or prayers, but consist rather of a rational training in a secular context. Therefore, just as children learn the importance of observing physical hygiene, they also need to cultivate an emotional hygiene. This means learning to tackle destructive emotions and cultivate those that are positive, which in the end is what actually helps us achieve peace of mind.

With my encouragement, a new K-12 education program has been developed by Emory University for international use. Social, Emotional, and Ethical Learning (SEE Learning), as it is called, entails a universal, non-sectarian, and science-based approach to the ethical development of the whole child in the course of his or her education. SEE Learning provides educators with a comprehensive framework for nurturing social, emotional, and ethical skills in their students.

If programs such as this can be combined with modern education, they have the potential to be of great benefit. Results will not be seen immediately, but as a new generation is brought up to respect and implement compassion, I’m hopeful that more altruistic leaders will emerge.

Your Holiness always remains very confident about the world and its potential, as well as very realistic. What gives you hope right now? It’s important to recognise that everyone has a right to happiness. There is no room for divisions into us and them. We need to think in terms of the oneness of humanity. Differences of nationality, race, religious faith, level of education are all secondary. We need to realize that other people’s problems are our problems too.

Physical pain can be reduced through mental exertion, but mental unease is not relieved by physical comfort. We need to nurture a concern for others’ well-being. Warm-heartedness reduces stress and brings calm to ourselves and to those around us; it gives rise to trust and trust leads to friendship. This I regard as a source of hope.

CORRECTION: This story was updated on May 18 to correct the photo caption and credit for the picture of Pico Iyer’s father, Raghavan Iyer, with the Dalai Lama.

You must be logged in to post a comment.