Saying Goodbye to the Great Gary K. Hart

A Politician Who Pushed Educational, Environmental, and Legislative Innovation

In Santa Barbara, Gary K. Hart walked on water. Unfailingly dignified, off-the-charts smart, thoughtful, serious to a fault, and solidly progressive, he represented this region in the California legislature first in the Assembly and then as senator. In 1998, he was appointed state Secretary of Education.

Every year — without fail — the California Journal would report that Hart ranked number one on matters of personal integrity in its much-awaited annual poll of statehouse pols, as well as their staff and the lobbyists paid to bend their ears.

Even for Hart, it got a bit much. “I think this integrity thing is overplayed,” he would say with some exasperation during an interview with reporter Jerry Cornfield shortly after Hart retired from office in 1994. “I’m not a saint. I’m a practicing politician.”

Saints aren’t necessarily that interesting. Good politicians almost always are.

I mention this because Hart died last Thursday after a losing fight with pancreatic cancer. He was 78. The weird thing is how poorly he is remembered by residents of the district he did so much to change during the 20 years he represented the area in Sacramento.

Maybe that’s partly because he decided early on to move with his wife, Cary, and their three daughters to Sacramento so they could have an actual family life, rather than commute back and forth as legislators regularly did.

Time is to blame as well. The Santa Barbara we’ve become — solidly, overwhelmingly, don’t-even-bother-talking-about-it Blue — wouldn’t recognize the Santa Barbara we used to be: Republican Red to its very marrow. That’s when Hart started his political career.

Hart was just 26 years old when he decided to run for Congress in 1970 against conservative Republican incumbent Chuck Teague. Hart’s only elected experience was as senior class president at Santa Barbara High School. And at the height of the Vietnam War, Hart campaigned as an antiwar candidate.

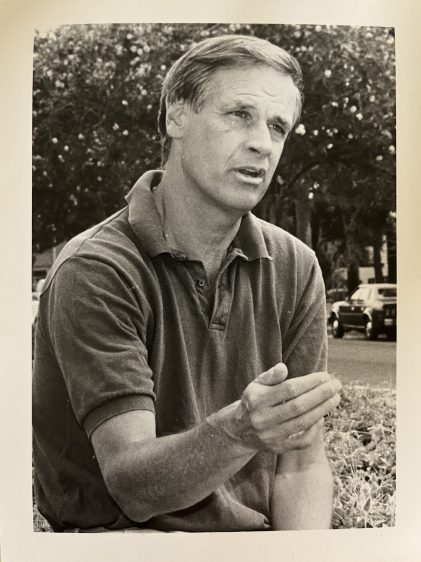

Hart had grown up in a Republican household himself. He was a high school football hero on Santa Barbara’s 1960 championship team. He was strait-laced and had short hair. He wore jackets and ties. He was a big guy — 6’4” — narrowly rescued from movie-star good looks by a big smile just shy of being goofy. In person, he was warm but reserved. He had a sense of humor but didn’t joke around.

Like many other young otherwise sensible overachievers in the 1960s, Hart got infected with that Kennedy bug that made him believe he could change the world. After graduating from Stanford and attending Harvard, Hart spent the Freedom Summer of 1964 in Mississippi. There he taught at an all-Black college and helped register Black voters. He also experienced the unholy terror that came with being a White teacher driving alone in a car with his Black students.

While still at Stanford, Hart met Allard Lowenstein — a talented political organizer focused on civil rights and ending the Vietnam War — who launched the unlikely Dump Johnson campaign in 1967 against President Lyndon Johnson. Hart spearheaded Lowenstein’s only successful campaign for Congress and also organized the presidential campaign of Senator Eugene McCarthy — outspoken against the war — in the New Hampshire primaries. Against all odds, McCarthy won more than 40 percent of the vote in that race. Not long after, Johnson announced he would not seek reelection.

That was before Hart ever ran for office.

Hart lost to Teague but posted a respectable 42 percent. He ran for State Assembly two years later against an incumbent who would later be named dumbest member of the legislator. He lost that one by just 700 votes. In 1974, he ran again for Assembly, this time for an open seat against a Republican insurance broker. He won.

Ronald Reagan — then governor — would question Hart’s “personal loyalty” as an American because he’d turned in his draft card while demonstrating against the war. (In almost every campaign since, Hart would face false accusation he’d “burned” his draft card.)

Sign up for Indy Today to receive fresh news from Independent.com, in your inbox, every morning.

At one point, Santa Barbara’s District Attorney — then a hardline Republican — launched a raid on Hart’s campaign headquarters here, alleging voter registration fraud. They came away empty-handed. But that didn’t stop KEYT News — then acridly hostile to Hart — from giving the story top billing. In North County, the masthead of the Lompoc newspaper read, “Missile Capital of the Free World,” with an illustration of two missiles forming the letter X. How could he connect with voters?

Hart’s strategy was simple: be straight and up-front. He never shied away from his antiwar, pro-choice, pro-gun-control, pro-feminist, anti-oil, pro-environment, anti-death-penalty, pro-decriminalization-of-pot positions.

He explained his beliefs with the clarity of the high school history teacher he’d been. But he didn’t preach. Instead, he reached out, forming alliances on specific issues with even infamous right-wingers such as Republican Assemblymember Ed Davis, the former police chief of Los Angeles. Everyone, Hart quickly came to understand, cared deeply about education. It happened to be something he knew about. It would become his signature issue.

As legislator, he surrounded himself with a smart, tough, get-shit-done, squeaky-clean staff of idealists. The most obvious example was Naomi Schwartz, who ran his district offices for years before embarking on her own political career. (As a county supervisor, Schwartz hired and mentored Salud Carbajal, who has since been elected three times to Congress.)

Among Hart’s first bills was a measure creating tax credits for solar energy — later amending it to include wind energy. It was the first such bill in the nation. He pushed a single-payer health insurance bill; that one — like the one proposed this year — went nowhere. He did, however, carry the legislation that created the Santa Barbara Health Authority.

He was big on childcare funding and child poverty issues. He got a bill passed prohibiting landlords from evicting tenants because they complained about sub-par conditions. He was forever clipping the wings of offshore oil development but also passed a bill giving county governments a cut in oil profits for the first time.

It’s for his education bills, however, that he’s most deservedly famous. In 1983, Hart got a major educational reform package approved, complete with the tax increase necessary to cover the $800 million in additional costs. He passed bills establishing competency requirements for graduating students and another requiring teachers to pass a competency test, known as the CBEST. (Both have since been repealed.) During the height of “The War on Drugs,” one of his opponents — former county supervisor DeWayne Holmdahl — challenged Hart to take a urine test for drugs. Hart replied he’d be happy to take the piss test if Holmdahl would take the CBEST test.

Hart’s signature bill — the one most mentioned in all the obituaries — was the one he passed in 1992 that would allow the for formation of 100 charter schools. The bill was bitterly opposed by the teachers’ unions because it did not require that charter schoolteachers be covered by collective bargaining agreements. Hart insisted the bill was necessary because it would give poor parents an element of educational choice. In addition, it would allow a desperately needed opportunity for innovation at a massive, notoriously dysfunctional bureaucracy. Today, there are around 1,300 charter schools, something over which Hart had expressed serious concern.

At the 11th hour and 59th minute, House Speaker Willie Brown — a rare genius when it came to Parliamentary procedure — announced that he killed the bill. But Hart — who played poker with Brown regularly — waited until most senators had left the chamber and then introduced the bill and won approval without debate. Before the lobbyists knew what happened, Hart had secured the signature of Governor Pete Wilson. As Hart noted, he was not a saint. He was a practicing politician.

And a damn great one.

I had the luxury of taking Hart for granted. So did we all. We should all be so lucky.

CORRECTION 2/7/22: Gary Hart took part in the Freedom Summer of 1964 not the Freedom Rides of 1961 as stated in an earlier version of this story. Also, Eugene McCarthy did not win the presidential nomination in 1968 but garnered enough of the vote to cause LBJ not to seek reelection.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.