Tales from Quintero’s Cave

Santa Rosa Island Dwelling Housed Otter Hunters, Sheep Shearers, and a Hermit

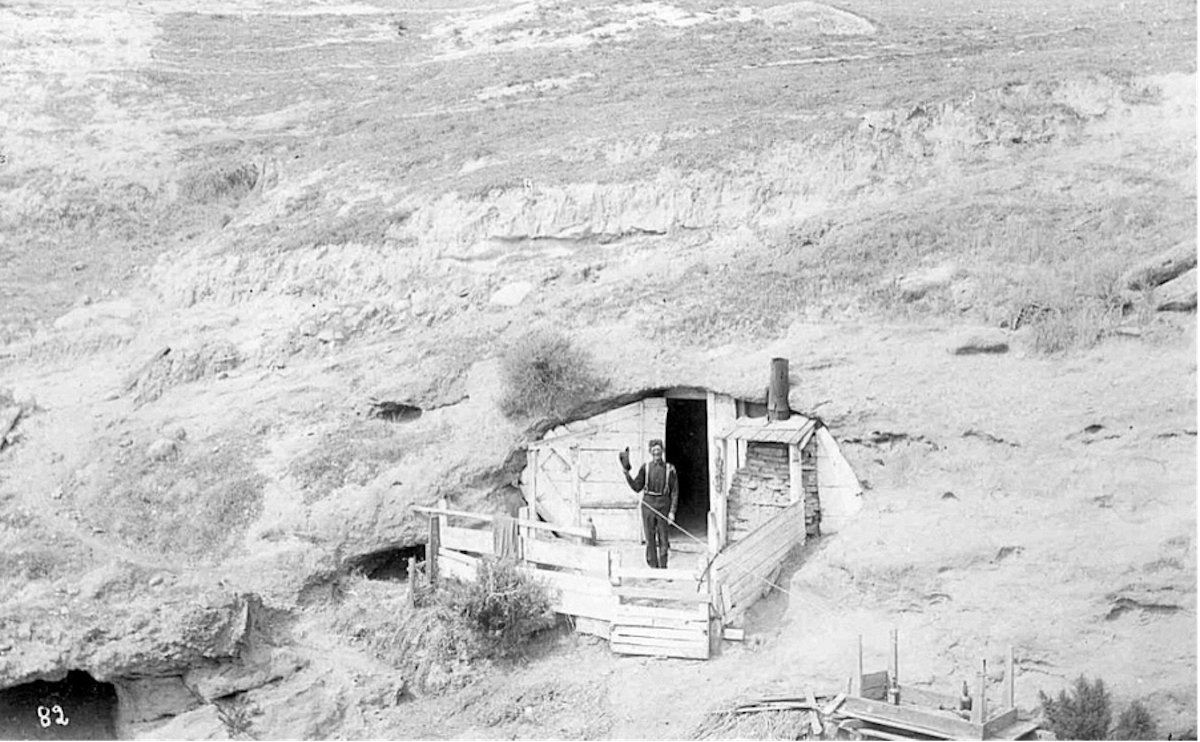

Mention of this Santa Rosa Island cave’s earliest use comes from pioneer otter hunter George Nidever’s recollections, The Life and Adventures of George Nidever (1802-1883). Nidever recounts using this cave to store gear and hide out from an attack by Aleut otter hunters in 1835. He described the cave as “so large inside that a hundred persons could occupy it with ease.”

Swedish zoologist Gustav Eisen visited the island in 1897 and wrote of the cave and its occupant:

“The strangest man of the few who live on Santa Rosa Island is Santiago Quintero. But Santiago might also be said to be one of the strangest men in the country. He is a hermit from choice and lives in a cave because he would rather live there than any other place in the world. Santiago is a man of some means and also earns some money from the estate, but he often spends months in his cave without seeing a person. He has a couple of dogs, who live in small caves near his, and together they are a happy family. Santiago’s cave is a natural hole in the rock, with the front boarded up and fixed with a door. He has a stove and plenty of good furniture, so that he is absolutely comfortable. He has lived alone in his cave for over thirty years.” [Overland Monthly, 1893.]

Quintero built a brick fireplace, the back of which closed off part of the cave entrance and had functional handmade furniture inside. Roughly 20 by 30 feet, the cave served as a cozy residence, complete with a fenced front yard and a wooden front door.

Quintero’s island residency spanned both the More years — during which time, according to naturalist and author Charles Frederick Holder, the cave was also occupied by sheep shearers — and the early part of Vail & Vickers island ownership. The 1910 U.S. Census lists him as age 73, living on Santa Rosa Island as a hired man and farm laborer. Seven years later, the Santa Barbara Morning Press (April 28, 1917) reports that Santiago Quintero was committed to the Patton State Hospital in San Bernardino County, the same hospital where Alonzo Wheeler of Santa Catalina Island ended up in 1894. According to the California death index, Santiago Quintero died on April 17, 1918.

The cave’s last use was as a cool storage place for dynamite used by Vail & Vickers for their road-building. When they constructed Smith Highway across Ranch House Creek, the road was placed directly over the top of Quintero’s Cave. Smith Highway is one of the key roads on the island. Leading from the ranch complex to the Arlington roundup and beyond to the west end, the road is named after C.W. Smith, longtime ranch foreman and dynamite expert. Smith built much of the road in the 1920s, blasting through rocky sections in Lobo Canyon and pulling the roadway in and out of deep ravines with precipitous entries and exits. Smith Highway follows the route dating from the mid-1800s that appears on Stehman Forney’s 1872-1873 topographic map of the island, which was used for sheep and cattle drives across the island for about 150 years, until the U.S. government ended cattle operations in 1998.

Today this intriguing cave is somewhat intact on the slope across Ranch House Creek from the barn complex, although it has largely filled with dirt because of holes that have developed in its ceiling, exacerbated by the construction of Smith Highway over the top. The ceiling is now between two feet and four feet high due to siltation. It has exceptional historic significance, and may contain layers of three or four cultures, from Chumash to otter hunters to sheep men and a hermit. Read more California Island history at islapedia.com.

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.