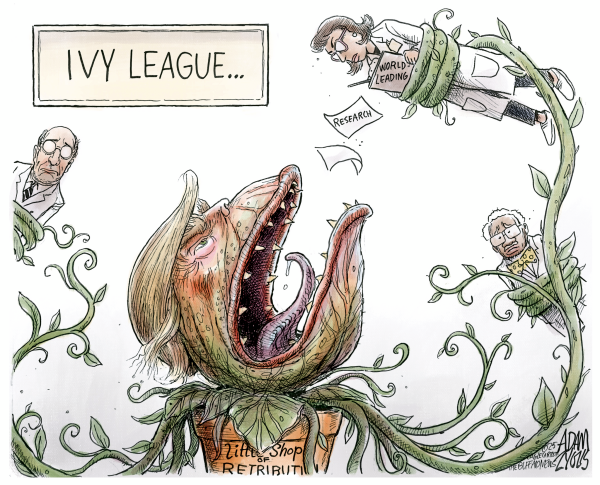

An important implication of President Trump’s escalating pressure on public universities points to a serious consequence for the quality of science that can be expected from American universities. Much of the economic and political status of our nation can be traced to the quality of research carried out here since the end of WWII. Public funding of cutting-edge research has led our universities to attract some of the best minds in the world to join these efforts. Trump’s punishment of leading universities by cutting research grant funding has potential implications for both our education and our economic future.

Ironically, we are also facing a parallel threat to the quality of our workforce from what is happening at the other end of the educational spectrum. For the past two or three decades, there has been a growing decline in the educational preparation of children entering our school systems. In California and in much of the nation, more than half of the children at any elementary school level cannot pass the state reading or math proficiency levels in yearly testing. Interestingly, longitudinal research from Great Britain has demonstrated that reading proficiency predicts math proficiency and not the converse. Literacy is at the core of educational success for most children, and probably this is true for their economic success, as well.

This problem has a history that goes back to a disagreement among reading specialists about the importance of young children entering kindergarten and first grade with a basic awareness of phonics, the code that links printed alphabet symbols to speech sounds. Data from neurological and learning developmentdicates that the age of four to five is the point at which the human brain is ready to begin to master this code. Unfortunately, the failure of our educational system to resolve this problem adequately means that about half the children entering our schools did not have parents with sufficient skills in reading to enable them to help their children enter school with basic prereading skills.

It is important to understand that there is now a readily available solution to this widespread developmental problem. The problem is that in many or most schools, the numbers of children entering school without these basic skills has increased to the point that it cannot be readily handled by teachers in the classroom. Acquiring skills in phonics is something that requires memorization and one-on-one instruction, preferably by the time they enter school. This is not when most preschool or kindergarten teachers have the time for a great deal of individual instruction.

Fortunately, there are now many individualized computer programs available to teach young children these skills, and there is good evidence that they work very well. The Utah state school board recently published the results of a controlled study of the effectiveness of eight computer-based programs for teaching young children basic phonics. All of them were found to be effective, statistically, and two of them had substantial effect sizes. One of these two programs was used in low-performing Santa Barbara preschool classrooms and reduced reading proficiency failure rates by as much as 80 percent, compared with a matched set of control schools.

Unfortunately, currently there is considerable resistance to using such computer programs with young children in schools. Some of this resistance may be linked to the earlier dispute about the current basis for literacy failure in our nation, but much of this resistance seems to be related to the idea that computers are replacing teachers in the classroom.

Ironically, the fact is that computers are making it possible for teachers to do the jobs for which they have been trained. Certainly, individual teachers could do one-on-one tutoring with young children, but then they would leave the rest of their class to someone not as well prepped to conduct group teaching.

The importance of attaining a high-quality workforce for the future is far too important to allow ideological and political disputes to stand in the way of recovering our national leadership in education and science. This statement applies to both national support for world-leading scientific research and to prepare young children with the skills to keep our economy strong. Both are concerns that have heightened significance currently.

John Coie is an Emeritus Professor of Developmental Psychology at Duke University. He lives in Santa Barbara.