SBMA Mounts Delacroix to Monet

Major Exhibition of 19th-Century Paintings from the Walters Art Museum

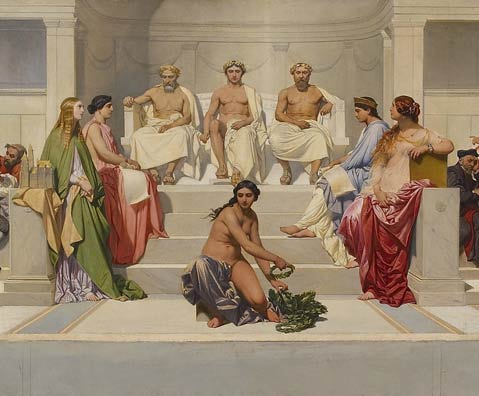

As we enter cinema’s awards season, it’s worth considering the cultural origins of artistic awards. In the upcoming exhibit Delacroix to Monet: Masterpieces of 19th-Century Painting from the Walters Art Museum, opening at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art on January 30, one painting in particular calls to mind this urge to honor artists, and puts them on the most exalted stage imaginable. Called “Replica of the Hémicycle,” this neo-classical masterpiece by two artists, Paul Delaroche and his student, Charles Béranger, represents the pantheon of the world’s greatest artists, who are gathered as if to honor you, the viewer, as the latest inductee to their hall of fame. The original mural, of which this important oil painting is the only other version, occupies 27 meters of wall space at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and functions as an integral part of the school’s graduation ceremony.

Laurels Earned

For the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (SBMA), Delacroix to Monet represents a similar kind of moment for the institution — a graduation to the very highest level of achievement in the category of regional museums. It demonstrates more clearly than anything that SBMA has done exactly what director Larry Feinberg meant by the “post-blockbuster” medium-sized tour de force shows he’s been promising since his arrival in March 2008. The 41 paintings that make up Delacroix to Monet not only represent all the major movements of 19th-century French art, from Neo-Classicism through Impressionism, they also stage the fundamental rivalry between neo-classicists such as Ingres and romantics such as Delacroix. Important paintings from outside of France — including a major work by J.M.W. Turner, a view of the Catskills by American Asher Durand, and Gilbert Stuart’s iconic 1835 portrait of George Washington — complete this staggeringly comprehensive view of Western art from 1795 (the date of the show’s earliest work, Rembrandt Peale’s “Portrait of Dr. Meer”) to the show’s latest work, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s “The Triumph of Titus: The Flavians” of 1885.

The Walters Art Museum reflects the taste and collecting habits of William T. Walters (1819-1894) and his son, Henry (1848-1931), a Baltimore-based father-and-son team primarily funded by successful investment in American railroads and commerce. A self-made millionaire by 1860, William Walters began collecting art with the Hudson River school, but soon found his way to Paris, where he developed a lifelong friendship and client relationship with another son of Baltimore, connoisseur and expatriate George A. Lucas. Together, they commissioned and bid on the works of virtually all the important contemporary French painters of the second half of the 19th century. What separates William Walters and his son from almost every other collector of the period is also what makes this show so exciting. The Walters, despite an early and lasting interest in the rival academic schools of Neo-Classicism and Romanticism, nevertheless understood and bought the Impressionists right from their controversial beginnings. Not only did Walters appreciate, for instance, the strikingly modern perspective of early Claude Monet, as one can see in the show’s lovely portrait “Springtime” (1872), he also had the nerve to go out in 1883 and have his portrait painted in the exaggeratedly modern manner of Edouard Manet by Impressionist Léon Joseph Florentin Bonnat.

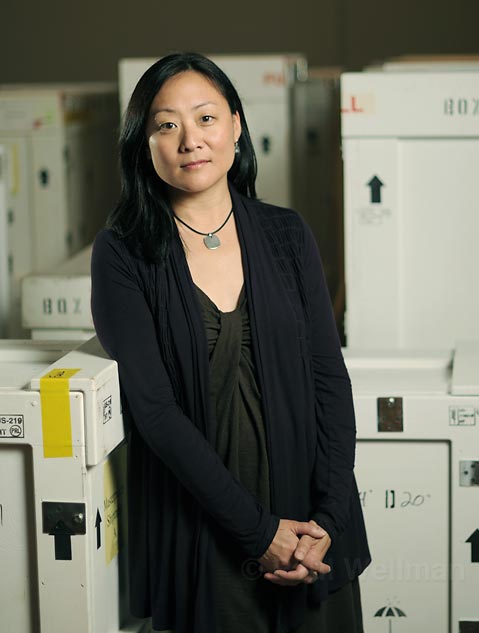

The curator of Delacroix to Monet, Eik Kahng, is new to the museum, but she is intimately familiar with these paintings, having curated the collection at the Walters prior to taking the position here. As SBMA’s new chief curator and curator of 19th- and early-20th-century European art, Kahng will play a major role in the direction of the museum in years to come. When she put together these pictures as a traveling representation of the Walters’ holdings, she had no idea that she would be joining them on the road, never mind in Santa Barbara, which is the exhibition’s only West Coast stop. For Kahng, installing Delacroix to Monet in Santa Barbara has been like unwrapping the best gift you ever picked out — and without knowing in advance that you would be receiving it yourself. For Santa Barbara, this fortunate coincidence is also a gift, as we are getting not just a great show and a top curator, but the fruits of a substantial scholarly engagement with one of the world’s most important collections of 19th-century art.

As a result of her keen appreciation not only of the 41 works of art on view, but also of the opportunity to display them at SBMA, Kahng has crafted a bold exhibition plan that takes full advantage of the museum’s two largest adjacent spaces, the McCormick and Davidson galleries. The McCormick will tell the story of French painting as a series of intriguing aesthetic episodes, beginning with Romanticism and Neo-Classicism and progressing through Orientalism to the urban Impressionism of Manet. In the Davidson, the break between two schools of landscape painting, Barbizon and Impressionism, takes center stage. As an example of just how exciting this show will be, imagine this opening sequence: a giant Turner flanked by wall text guarding the entrance to the McCormick Gallery, followed by two important Delacroix paintings of Jesus Christ on one wall, and Gilbert Stuart’s George Washington on the other. And that’s all before you enter the main room.

Portraits in Dialogue

Dominating the longest sightlines of each space are a pair of portraits drawn from the polar oppositions that embody the exhibition’s strongest theme, which is the dawn of modern subjectivity out of the combustible atmosphere of academic competition. At one end of the McCormick Gallery, Oedipus confronts the Sphinx in “Oedipus and the Sphinx” (1864), an eerie picture by neo-classical master Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. It’s an astounding work, and represents a heroic Oedipus who confronts and outwits the Sphinx despite the knowledge that a mistake would certainly cost him his life. Abstract expressionists Willem de Kooning and Barnett Newman worshipped Ingres, whose smooth, luminous surfaces and distorted figures and poses were a kind of abstraction avant la lettre. Curator Kahng, coyly referencing Freud, assured me that “this kind of placement is never an accident.”

Opposite Oedipus, in the analogous position at the end of the show, is a portrait of William T. Walters, the owner of the collection. It’s an extraordinary Impressionist work by Léon Joseph Florentin Bonnat from 1883, and it references an indelible icon of early Modernism, Edouard Manet’s 1880 portrait of the young Georges Clemenceau. Nothing could be more different from Ingres’s highly imaginary Oedipus than Bonnat’s life-sized snapshot of the imposingly real collector Walters. Yet, somehow, in the journey from ancient Greek tragedy to modern selfhood, extremes have been made to meet. Walters’s self-possession before the terrible honesty of the Impressionist gaze mirrors the confident way in which Oedipus confronts the potentially death-dealing Sphinx. It’s as though he were offering the history of painting as a civic gift to a beleaguered Baltimore, the riddle of her modernity to be solved by careful attention to his art collection.

A Metropolitan Museum of Art in Miniature

A wide range of real masterpieces by Pissarro, Degas, Sisley, Millet, and Millais appear throughout this show, lending credence to the Walters Art Museum’s claim to being a kind of mini-Metropolitan. What’s more, old rivalries and recent ideas from art historical scholarship percolate through the installation. In fact, the exhibit recalls an era — the latter half of the 19th century — when serious painting, more than theater, and rivaled only by literature, occupied the prestigious central position in popular culture accorded to motion pictures today. The arrival in Paris of the Napoleonic booty that founded the Louvre collection initiated an access to the masterpieces of the Renaissance and antiquity that in turn begat the French Academy style with its worship of Raphael and the opposing school of Romanticism that looked to Rubens for inspiration. The Paris Salons of the 1860s and 1870s generated the kind of buzz we get today from film festivals, and overflowed with gossip and excitement as well-financed artist/auteurs competed for such public laurels as the prestigious Prix de Rome.

This show really does appear as if it were a red carpet full of stars. There’s Edouard Manet, king of the urban hipsters, or flâneurs as they were known in the Paris of Baudelaire and Balzac. Over there are the Orientalists, masters of the exotic and the vividly sensual fantastic. Once wildly popular, then brushed aside before finally being dismissed as imperialist ideologues, artists such as the Dutch painter Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the Spanish Mariano José María Bernardo Fortuny y Carbó are, alongside the great French Romantic Eugène Delacroix, reemerging as emblematic figures in an ongoing international debate about the meaning of East/West polarity. For younger scholars such as Kahng, Edward Saïd’s critique of Orientalism was the stuff of undergraduate seminars, and these pictures are, through the magic of a generational renewal of perspective, once again available to fresh scholarly eyes and ideas. Where others in an earlier generation might have seen decorative images masking strategies of domination, today’s art historians observe the widening split between the formal ceremonies of cultural identity and the lived realities of mixed messages and indeterminate subjectivities.

Kahng makes a particularly strong case for Fortuny, placing him in a triumvirate between Goya on one side and Picasso on the other as the third most important modern Spanish artist. Certainly his two pictures in this exhibit, along with the reappraisal and celebration of his work going on in places like Southern Methodist University’s Meadows Museum in Texas, bear this judgment out. His “Portrait of an Ecclesiastic” (1874) predicts Francis Bacon’s screaming Pope perhaps more effectively even than its ostensible model by Velázquez. Fortuny painted his portrait of the ravages of religious office in the last year of his own life while in residence in Venice, the city that would provide a home and an atelier to his son, the famous designer and innovator in theatrical lighting.

The Painting of Modern Life

The whole first gallery, the McCormick, thus restages the 19th century’s high-stakes battle for control of and primacy within the visual field. At first it is myth that rivals history as the master subject for painting, then the exotic, and finally the modern and urban, but in a brilliant stroke, the exhibition turns in its second space, the Davidson, and phases from this struggle to another, supposedly more familiar one — the fight for the landscape. The story of 19th-century landscape painting generally is rendered as the displacement of traditional Barbizon landscape by Impressionism, and the exhibit does not so much contradict that version as restage it in a larger context.

In Delacroix to Monet, the familiar “triumph” of Impressionism reclaims its shock of the new from decades of mediocre reproductions and the neutralized homogeneity of endless calendars. Here, the sharp break signaled by technique, rather than promoting a “soft” version of the Impressionist vision, instead implies a fundamental change in world view, the visual equivalent of a scientific paradigm shift, with all the magnitude and consequences of the Copernican or quantum revolutions. In other words, the Impressionists did much more than find pretty ways to paint the atmosphere or let their brushstrokes show. They stepped through the looking glass of history into a radical project to portray the present moment from the point of view of a unique individual. Unlike the schools of the academy, in which deviation from the norm was defined as error, the Impressionists insisted on developing distinct and recognizable individual styles.

Was this emphasis on individuality a protest against the direction of history, with its harbingers of nationalist apocalypse to come? Or was it simply an anti-historical concept reflecting their collective faith in the inherent value of the present moment? Either way, Delacroix to Monet challenges the viewer to return to this watershed aesthetic divide and re-experience it along different and better-informed lines. By understanding the nuances of the academic painting that preceded the familiar Impressionist masters, one may freshen the sense of what Kahng terms “the utter rapidity of change in the art world” so characteristic of the modern era. Like the heroically reticent collector William T. Walters of Bonnat’s portrait, we may now stare the Sphinx of modern life in the eye and utter our own solution to the riddle of its representation.

4•1•1

Delacroix to Monet: Masterpieces of 19th-Century Painting from the Walters Art Museum opens on Saturday, January 30, at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art (1130 State St.) and shows through May 30. Visit sbmuseart.org for more information.