Purple Poo Bugs

Monitoring the Creek

One day, not too long after reading the Indy report about the Goleta Beach sewage spill, I took my four-year old son to visit his favorite splashing zones. What was unique about this outing was that, along with the sunscreen, hats and snacks, I brought the sterile tubes of a water monitoring kit.

At Goleta Beach, while I waded ankle deep to fill the first container, my son squatted barefoot to study a sideways-scuttling crab.

At La Cumbre Plaza, in front of the star-shaped bubbling fountain, I promised to bring enough bottles for the both of us next time.

At Devereux Beach, I forgot to lather the boy’s grubby fingers before handing him a quesadilla.

And at El Capitan State Beach, after balancing on a log to retrieve water from the deep part of the creek, I shook my wet hands before picking up the whining, cold, spent child. He curled his arm, which had gotten wet in the process, and wiped it on my shoulder. I thought nothing of it.

Back at home, I took two more samples, one from our drinking water. The last was from a place I’d never let any child play, our toilet bowl. Then I combined each sample with a specialized growth medium, poured them into Petri dishes, and put the lot into an incubator heated to body temperature. My plan was to grow bacteria associated with, well, poo.

High fecal bacterial levels detected in local creeks and beaches occur often after those much-looked-for rainfalls. In our area, one source is likely agricultural land: When manure from farmland is washed away during rain showers, associated bacteria find their way downstream to many prized play spots.

But sewage spills and faulty sewage or septic systems are also probable sources. Eww. In fact, a recent Northern California study showed that the septic system for a public beach was responsible for contaminating ground water that eventually spilled into the ocean. This report is significant because, despite lots of finger pointing, it’s one of the few that confirms such a connection scientifically.

Locally, stream and beach tests are performed weekly from April through October by the County of Santa Barbara Public Health Department’s Ocean Monitoring Program. As a consequence of budget cuts, testing during the winter (ahem, rainy) months no longer occurs. Now, the nonprofit organization, Santa Barbara Channelkeeper, picks up the remaining months. The data is a bit nauseating. Multiple local beaches routinely exceed California standards for bacteria associated with fecal pollution.

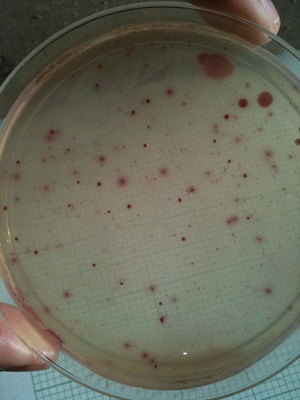

Back in my garage and 24 hours later, some plates were growing the nasty poo bugs. The test’s color indicator showed purple spots for E. coli. And pink colonies represented the more general coliforms (often associated with fecal waste but also found in soil). While the bacteria themselves can cause illness and infection, their presence also indicates a risk for other serious pathogens such as hepatitis.

As expected, and despite the chlorination of household water, our toilet bowl showed a robust population of E. coli—purple and prominent. The number of spots, or colony numbers, for this sample however, were lower than threshold for California’s state standards. Whew, I guess. Most of the other samples, including the suspect, Goleta Beach, showed even lower or in some cases undetectable levels.

But there was one unexpected result. With a smattering of purple and pink dots, the counted colonies of this particular dish exceeded not only my bathroom sample, but also the cutoff for the state standard. And while my “experiment” was less than scientific, lacking true controls and replications, the levels from the creek at El Capitan were consistent with the week’s formal sampling results—results warranting a red WARNING status to post in the report, which I saw only after making the concerted Internet-effort.

At El Capitan State Beach, the mouth of El Capitan Creek is adjacent to a giant green field, the park’s septic system leach field. There are also nearby farms.

Richard Rozzelle, the district superintendent for California State Parks, Channel Coast, keeps tabs on all pertinent bacterial spikes. “I’m glad Channelkeeper stepped in,” he said. “It’s good data to have and it’s something we continue to monitor.” Rozzelle has one past experience with sewage pollution culminating in a critical public safety concern. “It was a lot to undertake,” he told me. “As a steward for Parks, I’m concerned with public health and water quality.”

The state and county budgets being what they are, Channelkeeper’s Stream Team Volunteer Program is one way the community can pool efforts. Taking several samples throughout the year, at multiple points along the creek, supplies data that can pinpoint consistent and serious purple problem areas. Perhaps I wasn’t just appeasing a four-year old when I said that next time I’d bring more bottles.