How the Irish Saved Mission Santa Ines

Why Ireland’s Capuchin Franciscans Went West 100 Years Ago

Amid the red tile roofs, white-washed adobe walls, arched colonnades, and towering campanile of Mission Santa Inés, there lies a lush garden set in the shape of a Celtic cross, the tombstone of a beloved Irish freedom-fighter, and the quiet footsteps of brown robe-wearing sons of the Emerald Isle. These pious men hail from the Capuchin order of Franciscan friars, and their legacy explains how this architectural gem of the Spanish colonial era also happens to be an ode to Irish heritage. It’s a surprising pairing even in the culture clash of California, but if it weren’t for the Irish, there just might not be much left of Mission Santa Inés, whatsoever — and most certainly it would not be the vibrant Catholic community and lovingly restored landmark that it is today.

“It’s a busy place,” said 71-year-old Father Gerald Barron in a lilting brogue last week, he being one of the last two native Irish priests stationed at the mission after more than 80 years of Capuchin care. “You’re doing two things at once: running a parish and running a historic monument.”

While the history of the Capuchins goes back to the early 1500s, the West Coast era starts exactly 100 years ago, when the order was brought from its Irish stronghold of County Cork to Oregon to establish a new diocese between Bend and Hermiston, a wide swath of land roughly the size of Ireland itself. “The West Coast was pioneer territory for the Catholic Church back then,” explained Father Gerald, so the Irish order soon sent more priests to Mendocino and later to the archdiocese in Southern California. In 1923, the Capuchins founded St. Lawrence of Brindisi parish in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts, and the church has since served as a beacon of hope to the impoverished South Central masses.

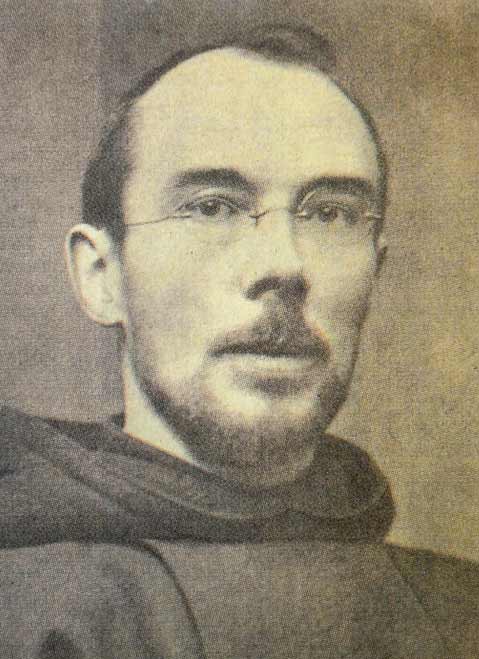

In November 1924, a friar named Albert Bibby made his way to Mission Santa Inés and found it a crumbling mess, despite earnest renovation attempts by the outgoing priest, Father Alexander Buckler. “The place was falling down when he came to it,” said Father Gerald, who has unearthed old letters from the era showing how daunting a task it was. In bringing modern plumbing and electricity to the mission, Bibby was joined by friars Reginald O’Hanlon and Colmcille Cregan, who landscaped the mission’s garden into a pattern of the Celtic cross a couple years later. “It’s amazing to see what these men did,” said Father Gerald. “What they went through just establishing this place is nothing like I had to do. They put in the groundwork.”

Even though he was a sickly man, Bibby took on his new role with gusto, for he’d been given a prayer card of Saint Agnes (the English translation of Inés) as a young priest and developed a deep devotion toward her. But his time at Mission Santa Inés would be short; he died at St. Francis Hospital in Santa Barbara only three months later and was buried just outside the mission’s chapel.

However, Bibby was a hero in Ireland, where he was known as the “Patriot Priest” for his involvement in the country’s fight for freedom against the British. So in 1958, Bibby’s body was exhumed and taken back ceremoniously to Ireland, along with another West Coast Capuchin named Dominic O’Conner. It was a grand undertaking, recalled Father Gerald, who witnessed the event firsthand as one of the young priests who led the procession from the city of Cork up a rural road to the Capuchin monastery, where Bibby was interred. Though his body went home, Bibby’s gravestone was left intact at Mission Santa Inés out of deference to his brief but strong influence. It still sits there gathering moss and is visited often by mission-goers.

By 1947, the Mission Santa Inés restoration was in full swing. Among other improvements, the Capuchins added a second story to represent the mission as it was before the disastrous earthquake of 1812. Using old photographs as guidance, the Capuchins remodeled the bell tower to look as it had before collapsing in 1911, and repaired the old bell just in time to ring it proudly for the mission’s 150th anniversary in 1954. Three decades later, the Irish-born Capuchins commissioned two new bronze bells for the tower, which were installed in 1984. They also built a series of historically accurate arches, and by the early 1990s were focused on restoring the mission’s many paintings, some of which date back to the 17th century. Today, the Capuchins’ work can be enjoyed in many ways, whether by walking the pristine grounds, learning about the myriad research projects that they sponsor, or touring the museum while listening to one of the speaker boxes that tell the stories of yesteryear.

Father Gerald, who grew up in Dublin and left a coveted job at the Guinness brewery to enter the priesthood, came to California in 1963 and has worked up north in the Bay Area and down south at the Capuchin-run high school in La Cañada-Flintridge, and tallied 16 combined years during three stints in the Santa Ynez Valley, both at the mission and at the San Lorenzo Retreat House. In 1985, the Capuchins officially started a province to enlist priests from California, Nevada, Arizona, and Mexico, so the supply of Irish priests began dwindling. “I’m the last of the Irish,” said Father Gerald, explaining that there are only about a dozen Irish-born priests left on the West Coast.

Despite playing a starring role during the end of an era, Father Gerald’s not particularly worried about continuing Ireland’s West Coast legacy. Rather, he and the other Capuchins are more focused on ensuring that their order survives, for priests aren’t signing up like they used to. Vocations are “booming” in places like Africa, Indonesia, and Brazil, said Father Gerald, “but in Europe and the States, we’re struggling.” He does boast a strong hope for the future in Mexico, where the Capuchins expanded their focus 25 years ago. “That’s where the life of the order is for us right now,” he said.

Although challenges persist, the Capuchins are striving to make 2010 a year of centennial celebrations to honor those first friars who came to Oregon in 1910. As such, the Mission Santa Inés is hosting a big bash on March 14 (which is already sold out) that will double as a St. Patrick’s Day party as well, complete with corned beef, cabbage, and plenty of Irish jigging. During the rest of the year, the mission will be displaying historical documents and photographs in memory of Father Bibby, as well as other artifacts that tell the Capuchin tale.

Thankfully, dusty documents and tattered photos aren’t the only memories of how the warm Irish spirit invigorated the almost forgotten mission. Just spend a few minutes chatting with Father Gerald, whose kindness and wisdom are guiding lights for all people. You’ll quickly realize that the sons of Ireland are still very much the heart and soul of Mission Santa Inés.

4•1•1

See missionsantaines.org or call 688-4815 for more info on Mission Santa Inés and olacapuchins.org for more info on the West Coast Capuchins. The Capuchin’s March 14 centennial celebration is already sold out, but the order’s leader, Father Mauro Johri, will say a special Mass on April 13 at 7 p.m.